magazine text block

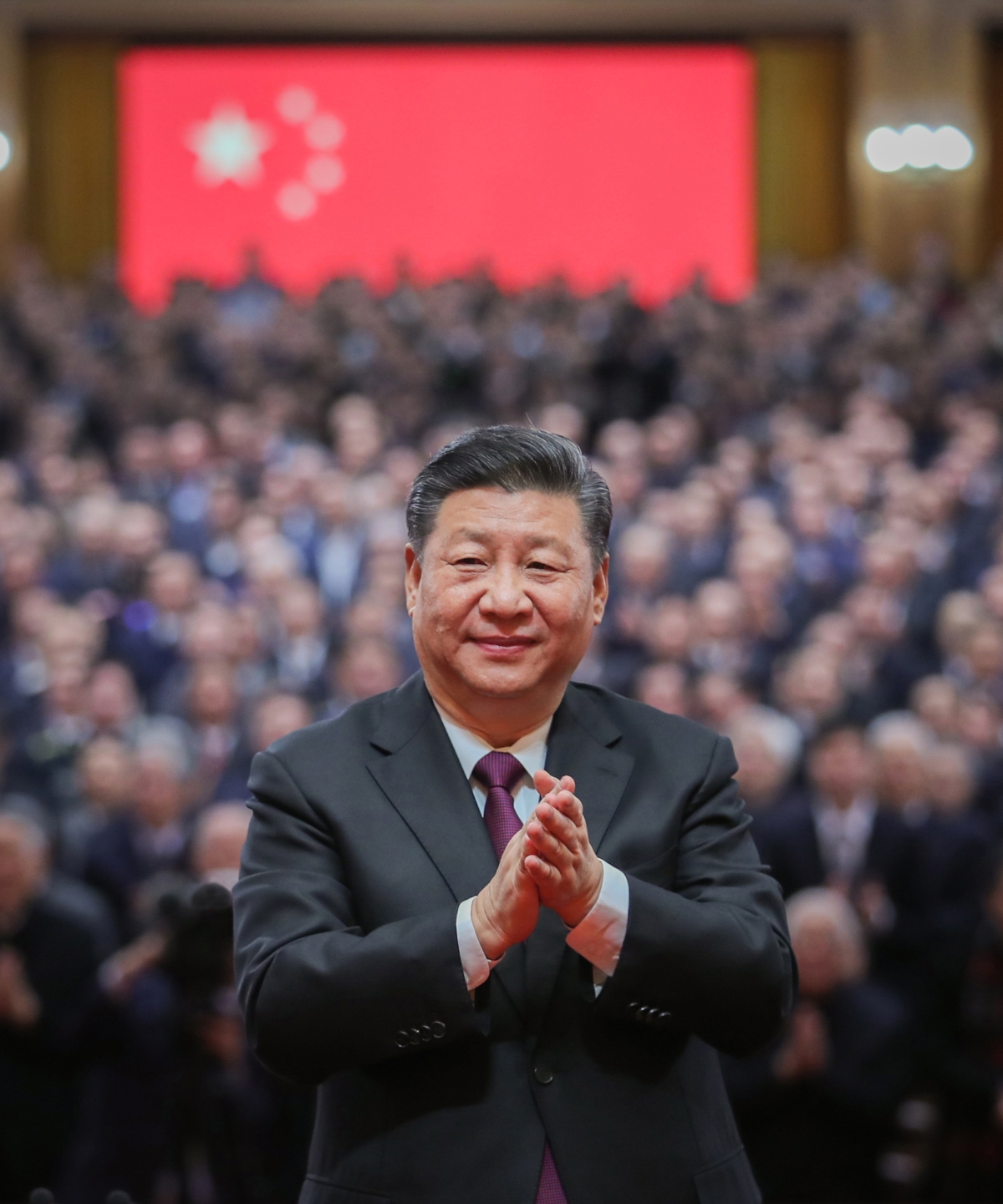

Xi Jinping sits at the apex of the Chinese political system. But his influence now permeates every level. In 2013, I wrote that Xi would be China’s most powerful leader since Deng Xiaoping. I was wrong. He’s now China’s most powerful leader since Mao Zedong.

We see this at multiple levels. The anti-corruption campaign he’s wielded across the Party has not only helped him “clean up” the country’s almost industrial levels of corruption. It has also afforded the additional benefit of “cleaning up” all of Xi’s political opponents on the way through.

None of this is for the fainthearted. It says much about the inherent nature of a Chinese political system that has rarely managed leadership transitions smoothly. But it also points to the political skill craft of Xi himself.

There is little Xi hasn’t seen with his own eyes on the deepest internal workings of the Party. He has been through a “masterclass” of not only how to survive it, but also on how to prevail within it. For these reasons, he has proven himself to be the most formidable politician of his age. He has succeeded in pre-empting, outflanking, outmaneuvering, and then removing each of his political adversaries. The polite term for this is power consolidation. In that, he has certainly succeeded.

The external manifestations of this are seen in the decision to formally enshrine “Xi Thought” as part of the Chinese constitution. For Xi’s predecessors — Deng, Jiang Zemin, and Hu Jintao — this privilege was only accorded to them after they had formally left the political stage. In Xi’s case, it occurs near the beginning of what is likely to be a long political career.

A further manifestation of Xi’s extraordinary political power has been the concentration of the policy machinery of the Chinese Communist Party. Xi now chairs six special “central committees” covering almost every major area of policy.

But perhaps the greatest manifestation of Xi’s accumulation of unchallenged personal power has been the decision to remove the limit of two five-year terms on those appointed to the Chinese presidency.

Xi is now 66 years old. He will be 69 by the expiration of his second term as president, general secretary of the Party, and chairman of the Central Military Commission. Given his own family’s longevity (his father lived to 88, and his mother is still alive at 94), as well as the general longevity of China’s most senior political leaders, it is prudent for us to assume that Xi, in one form or another, will remain China’s paramount leader through the 2020s and into the following decade.

He therefore begins to loom large as a dominant figure not just in Chinese history, but in world history, in the 21st century. It will be on his watch that China finally becomes the largest economy in the world, or is at least returned to that status (which it last held during the Qing dynasty).

magazine text block

Finally, there is the personality of Xi himself as a source of political authority. For those who have met him and had conversations with him, he has a strong intellect, a deep sense of his country’s and the world’s history, and a deeply defined worldview of where he wants to lead his country. Xi is no accidental president. It’s as if he has been planning for this all his life.

It has been a lifetime’s accumulation of the intellectual software, combined with the political hardware of raw politics, that forms the essential qualities of high political leadership in countries such as China. For the rest of the world, Xi represents a formidable partner, competitor, or adversary, depending on the paths that are chosen in the future.

There are those within the Chinese political system who have opposed this large-scale accumulation of personal power in the hands of Xi alone, mindful of the lessons from Mao. In particular, the decision to alter the term limits concerning the Chinese presidency has been of great symbolic significance within the Chinese domestic debate. State censorship was immediately applied to any discussion of the subject across China’s often unruly social media.

For Xi’s continuing opponents within the system, what we might describe as “a silent minority,” this has created a central, symbolic target for any resentments they may hold against Xi’s leadership. It would be deeply analytically flawed to conclude that these individuals have any real prospect of pushing back against the Xi political juggernaut in the foreseeable future. But what these constitutional changes have done is make Xi potentially vulnerable to any single, large-scale adverse event in the future. If you have become, in effect, “Chairman of Everything,” then it is easy for your political opponents to hold you responsible for anything and everything that could go wrong, whether you happen to be responsible for it or not.

This could include any profound miscalculation, or unintended consequence, arising from contingencies on the Korean Peninsula, Taiwan, the South China Sea, the Chinese debt crisis, or large-scale social disruption arising from unmanageable air pollution or a collapse in employment through a loss of competitiveness, large-scale automation, or artificial intelligence. This could come from international fallout over Xinjiang, how events unfold in Hong Kong, or his handling of the coronavirus crisis.

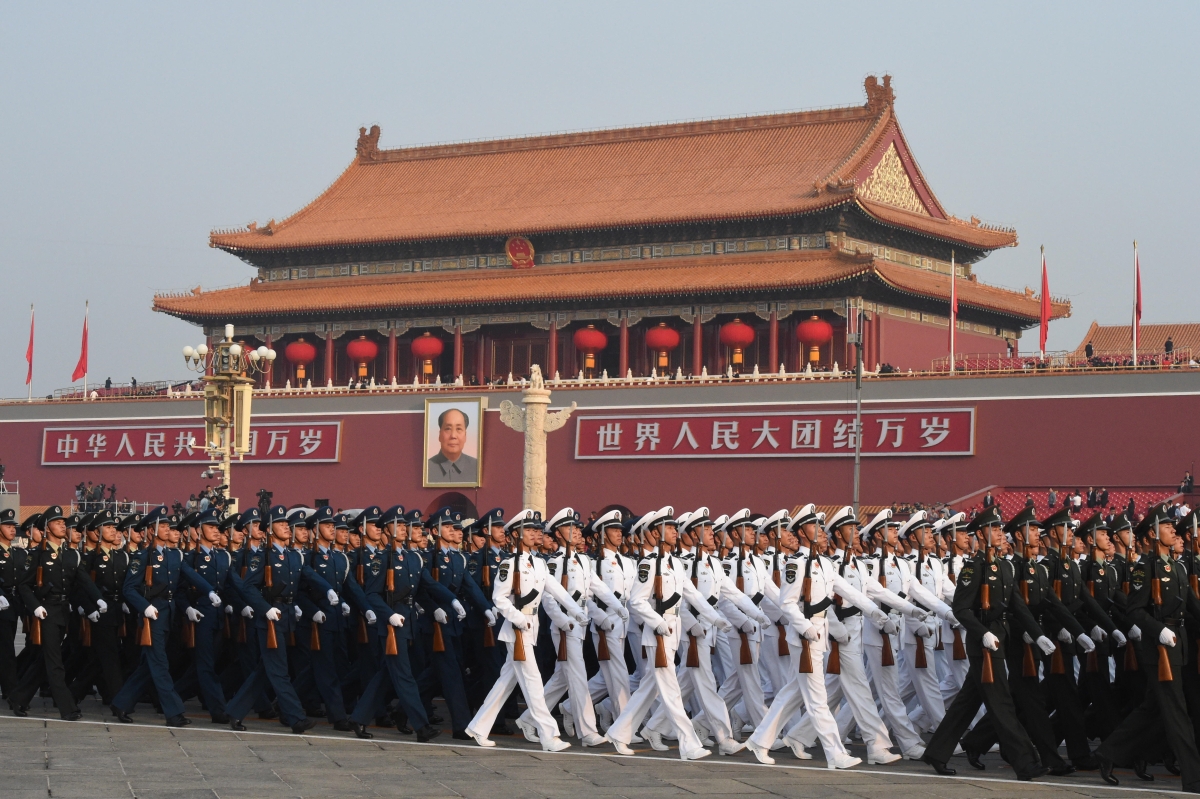

Troops prepare for a military parade marking the 70th anniversary of the founding of the People's Republic of China, in Beijing on October 1, 2019.

Li An/Xinhua/Alamy

magazine text block

However, militating against any of the above, and the “tipping points” that each could represent, is Xi’s seemingly absolute command of the security and intelligence apparatus of the Chinese Communist Party and the state. Xi loyalists have been placed in command of all sensitive positions across the security establishment. The People’s Armed Police have now been placed firmly under Party control rather than under the control of the state. And then there is the new technological sophistication of the domestic security apparatus right across the country — an apparatus that now employs more people than the People’s Liberation Army.

We should never forget that the Chinese Communist Party is a revolutionary party that makes no bones about the fact that it obtained power through the barrel of a gun, and will sustain power through the barrel of a gun if necessary. We should not have any dewy-eyed sentimentality about any of this. It’s a simple fact that this is what the Chinese system is like.

Apart from the sheer construction of personal power within the Chinese political system, how does Xi see the future evolution of China’s political structure? Here again, we’ve reached something of a tipping point in the evolution of Chinese politics.

There has been a tacit assumption, at least across much of the collective West over the last 40 years, that China, step by step, was embracing the global liberal capitalist project. Certainly, there was a view that Deng’s program of “reform and opening” would liberalize the Chinese economy with a greater role for market principles and a lesser role for the Chinese state in the economy.

A parallel assumption has been that over time, this would produce liberal democratic forces across the country that would gradually reduce the authoritarian powers of the Chinese Communist Party, create a greater plurality of political voices within the country, and in time involve something not dissimilar to a Singaporean-style “guided democracy,” albeit it on a grand scale.

Many scholars failed to pay attention to the internal debates within the Party in the late 1990s, when internal consideration was indeed given to the long-term transformation of the Communist Party into a Western-style Social Democratic Party as part of a more pluralist political system. The Chinese were mindful of what happened with the collapse of the Soviet Union. They also saw the political transformations that unfolded across Eastern and Central Europe.

Study groups were commissioned; intense discussions were held. They even included certain trusted foreigners at the time. I remember participating in some of them myself. Just as I remember my Chinese colleagues telling me in 2001 and 2002 that China had concluded this debate, there would be no systemic change, and China would continue to be a one-party state. It would certainly be a less authoritarian state than the sort of totalitarianism we had seen during the rule of Mao. But the revolutionary party would remain.

The reasons were simple. The Party’s own institutional interests are in its long-term survival: after all, they had won the revolution, so in their own Leninist worldview, why on earth should they voluntarily yield power to others? But there was a second view as well. They also believed that China could never become a global great power in the absence of the Party’s strong central leadership. And that in the absence of such leadership, China would simply dissipate into the divided bickering camps that had often plagued the country throughout its history.

These internal debates were, of course, concluded a decade before Xi’s rise to power. His should not be interpreted simplistically as the sudden triumph of authoritarianism over democracy for the future of China’s domestic political system. That debate was already over. Rather, it should be seen as a definition of the particular form of authoritarianism that China’s new leadership now seeks to entrench.

This text was adapted from an address to cadets delivered at the United States Military Academy, West Point, New York in March 2018.