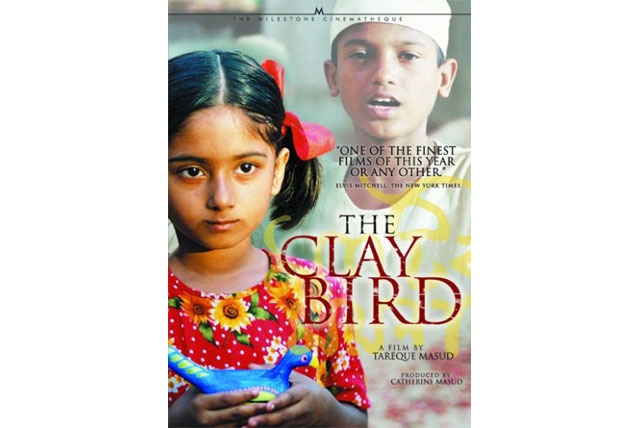

Interview: Tareque Masud, Director of 'The Clay Bird'

Tareque Masud is a filmmaker based in Dhaka, Bangladesh. With Catherine Masud, he has produced numerous documentaries and shorts through their production company, Audiovision. Matir Moina, or The Clay Bird, premiered at the Cannes Film Festival in 2002 and is their first feature film.

In this interview, Tarque Masud discusses, among other themes, his childhood experience in a madrassah, the significance of Sufi mystical traditions in Bangladesh, depictions of political violence in the media, the making of The Clay Bird, the role of music and architecture in the film, and his future plans.

The Clay Bird is your first feature film. To what extent is it autobiographical? And how important do you think it is that you are able to present a story from the inside as it were, as a Muslim, as a Bangladeshi, and so on?

Well, first of all, it is definitely very autobiographical because all the characters and events are very close to the reality of my own life. Second, we are basically documentary filmmakers. If I could have, I would have made a documentary on my life, but it is virtually impossible to do that because it is too close to me.

Because the film so closely resembles the events of my own life, it is also a journey into my self, my community, my religion. I think one of the reasons why the film may have some strength is because I am an insider. Madrassahs have mostly been talked about by outsiders who have never been to a madrassah, and also of course they are mentioned a lot now in the western media and press. Even in countries where madrassahs are a big phenomenon like Pakistan, Bangladesh, and India, the people who talk about madrassahs are the middle class who neither attend madrassahs themselves nor send their children to study there.

It so happens that the film was scripted, shot, and finished before 9/11. After 9/11, though, the madrassah became very topical. In my case, however, the madrassah was simply a part of my life; I had been carrying inside me both the pain and the pleasure of my experience there. It was not like I wanted to share it with outsiders but I had wanted for a long time to share it with my fellow Muslims who are not familiar with the madrassah. One of the reasons for this, as I mentioned, is that hardly any middle class children are sent to madrassahs.

When I was in college, my classmates would ask me what school I attended and I tried at first to evade the question. When I did tell them that I attended a madrassah there was a tremendous curiosity among my peers about my experience there. I should add that the college I attended was co-ed so it was even more of a dramatic change for me coming from the madrassah!

I then started thinking that I should do something with my experience at the madrassah. Following college, I got involved in the film society and I started watching a lot of interesting films, including Pather Panchali by Satyajit Ray. I then started thinking of making a film about it.

It just so happened that being in New York, where I was from 1989 to 1995, gave me more perspective on the idea. When you are a away from home, you have more perspective in general, and especially so in as multicultural, multiethnic city as New York. It was then that Catherine and I really started talking about it, about going back to Bangladesh to start preparing ourselves to make a film on my experience in the madrassah.

What is the significance of the title Clay Bird?

In the film, as you may recall, my character comes home from the madrassah for a holiday and stops at a village fair and picks up this clay bird to give to his sister. This is what happened in my own life; I bought this clay bird for my sister and it came to have a strong association with my sister's memory. It means a lot to me because of what happened to her later. The clay bird was poignant for me, for the memory of my sister, because even at that age, we knew that our father would not approve of us having it - it was considered pagan. And of course, as children, we were much more inclined to find something curious and interesting because it was forbidden. When other children used to play with such idols (dolls and such things) my father would forbid us from doing the same.

I remember the time in the late-60s when plastic dolls were first becoming available for ordinary middle class families. When I visited Dhaka, I used to see my cousins play with them but I knew I would not be able to take these dolls back home. And it was the same with my sister - she was deprived of playing with the dolls which all her cousins and friends had; this was particularly hard in our rural context where there were so many fairs with toys, figurines, dolls and so on. So that was one of the main reasons for choosing the title: its association with my childhood and my sister.

It is also a thematic part of the film: the question of freedom versus different kinds of human limitations - social, political, and religious. As Sufism teaches us, the human being is made of clay and the soul is always associated with a free bird. The soul is encaged in a clay body and the body is very limited, very transitory, fragile, weak; the soul always wants to be free, has an immense desire to be free. If there is any continuous and recurring theme in the film it is freedom despite limitations, whether they are social, political, or physical. Aisha wants to be free as a woman, as a human being; Anu wants to be free to do whatever he wants to do; Milon seeks national, territorial freedom which is his own narrow sense of freedom; the boatman talks about a greater, mystical, spiritual freedom. So all the characters are pursuing their own forms of freedom. The theme of freedom recurs even against the backdrop of the political movements depicted in the film. So the overriding theme is limitations versus freedom, and the title reflects this and is a tribute also to Sufism, and its emphasis on the relationship between soul and body.

You have brought out brilliantly the importance of Sufi mystical traditions in rural Bangladesh, and also the long history and practice of religious pluralism and internal debate within Islam - the theological sophistication of popular religion, as it were. In the last song in particular, there is a very interesting dialectic between orthodox and mystical Islam in which mystical Islam wins out at the end of the song, when the woman singer initially taking the orthodox position joins the mystical/humanist position. Do you think that popular religion is mystical/humanist, and orthodox religion is an artifact of the state, in particular the Pakistani state?

I cannot say specifically for a state like Pakistan. I would say, in general, for countries like Pakistan or Bangladesh, or any other Muslim country, but in the case of Bangladesh particularly since this is the country I know best, popular Islam is definitely based more on "real" life. In this context, popular Islam is more inclusive, more pluralistic, more diverse and syncretic in nature, based on wisdom and common sense. This is in sharp contrast with what I call "scholastic" Islam, a bookish and modernist Islam (and this modernist phenomenon is not limited to Islam; it is more widespread and has an effect on all religions). The modernists are using this scholastic Islam for their own ends. They are trying to impose a creed and not the culture, even though clearly Islam is not just a creed, it is a culture like any other. A big part of religion is culture.

Modernists everywhere are trying to impose an abstract creed, to impose Islam from a scholastic point of view, from a book, and this has historically never been popular. Popular Islam grew naturally with strong support from the Sufi mystic tradition. In South Asia, Islam did not travel with the sword; the soil may have in certain places been conquered by the sword, but the soul was conquered by Sufism. What is more important: conquering the soil or conquering the soul of the people? People's hearts were won by Sufis. This is not just simple rhetoric; this is how it happened. In Iraq now for instance when you try to conquer peoples' minds, it is not easy to do with the sword. If you want to conquer somebody's heart you need to follow a different path.

In this way, I see popular Islam as very deep-rooted in Bangladesh. There is a strong Sufi influence across South Asia which can be seen in the shrines to Sufi saints across the region. People have a much more natural inclination towards this form of religion. It is very close to their hearts; they do not need to be indoctrinated. They can appreciate saints and shrines, and celebrate and worship God through songs and music.

There is another dimension to Islam, that is, its diversity: in Bangladesh, Islam is integrated very much with indigenous cultures. Islam is as diverse as the cultures and countries it exists in, which is the beauty of it. It is beautiful that Islam adopts the local traditions and cultures; that is the greatness of any big religion, it does not impose itself.

Do you think that this humanist, Sufi tradition of popular Islam is under threat in Bangladesh today? How do you see the post-independence history of the syncretic nature of Bangladeshi identity?

The creation of Bangladesh was quite unlike the creation of Pakistan which was more or less created because of Islam, because of the Two-Nation Theory (that Muslims needed a separate nation based on religion). Bangladesh was created on the basis that the state has nothing to do with religion. From this there has definitely been a departure as far as both the constitution and government are concerned. From 1975 onwards we went back to the Pakistani legacy of military governments. Since the military never has a base to get popular support, they always use religion. Although the leaders have had no interest in Islam they would always include Islamic elements in the constitution to gain support. They would become self-appointed guardians of Islam, alleging that Islam was in danger and that they would protect it (all, of course, for their own vested interests).

We went through that kind of phase, unfortunately. The constitution has still not been reversed. There were amendments made to the constitution that made it less secular. Then, in response to 9/11 and the atrocities against Muslims in India, there was a serious backlash in Bangladesh. There has been a rise in Islamic fundamentalism but Islamist parties have yet to gain popular votes in elections. This is definitely a reaction to what is happening in the Middle East and is more understandable when looked at in this context. At the same time, however, as we already discussed, there is a very strong popular Sufi influence in rural Bangladesh.

There is another equally important factor: in 1971, some of the major Islamic parties were involved in war crimes as collaborators with the Pakistan army. During every election, this is brought back; the war-crime stamp hurts their credibility so that works as a safeguard. It is very difficult for them to be elected given that legacy. Even in Pakistan, until now, no Islamist party has come to power.

Music is very important to the film. Could you say a little bit about the songs and the music, what tradition they come from, what their relevance is to the themes you discuss?

First of all the songs are about a living culture, not just the culture of the 1960s. This is a great tradition that took its inspiration from a combination of different influences including the Islamic Sufi traditions of literature (specifically Sufi poetry), Vaishnava mysticism and Buddhist mysticism. Before the Buddhists were driven out of South Asia by the Brahmins, East Bengal was their last refuge and since a lot of Buddhist culture remains, there is a lot of Buddhist music. It is called 'Baul' in Bangladesh, which is rapidly gaining in popularity now. Most striking is the fact that there are a lot of women singers. The women who appear in the film as singers are not actresses but actually real singers. They are called 'Boyati' singers and are very popular. Unlike in the film, where you see only three or four minutes of them singing, many of them sing for several hours at a stretch: frequently from 10:00 pm to 6:00 am, and much of the song is frequently improvised.

Baul culture is becoming more popular and having a big influence on young urban bands. These bands are finding great inspiration in Baul culture, and are remixing a lot of Baul Sufi songs. You see this in other South Asian countries as well, but Bangladesh has a very distinct Baul culture, which is being revived by this young generation's work. It is striking that the egalitarian philosophy of Baul music is not only having influence in rural areas but also among the urban, educated middle class, which I think is wonderful. It is the best thing that could happen with this great tradition.

The beauty of the Bengali countryside has long played a role - say, from Rabindranath Tagore onwards - in Bengali nationalism. Your film, too, celebrates the magnificence of this countryside. Do you see yourself as part of that tradition?

In some ways, yes and in others, no. In contrast to the cities, the countryside in Bangladesh is beautiful but that is of course true in any country. There are films that deliberately make an effort to show beautiful landscapes. This is a trap. Bangladesh has a wonderful, diverse landscape, despite being a relatively flat land. However, I do think we deliberately avoided getting into the trap of showing the physical beauty of the country. What we tried to capture was the inner beauty of ordinary people in villages, an inner beauty born of their culture. They are not stars with beautiful faces but ordinary hard working peasants with their own beauty. It is not a lyrical film in that sense. We focused more on the culture - the festivities, the recitations, the village fairs, Eid - and inner beauty than the landscapes. In other Bengali films - with all due respect to great masters like Satyajit Ray - there is a tremendous tendency towards lyricism and romanticizing the village or rural Bangladesh and we consciously avoided that.

When films are made in Muslim-dominated countries, it seems that we copy not only the style and technique of Hollywood and Bollywood, but also the cultural content. Very rarely will you see a South Asian film showing the culture of a Muslim family, or Muslim rituals. Initially even we shied away from that. But then with this film, we tried to capture the complex fabric of Muslim culture through everyday life: family, the prayer, wuzu, and the other rituals of this Muslim family.

Pather Panchali to me is a great inspiration. I am a great admirer of Satyajit Ray and his simplicity. I consciously tried to reproduce this simplicity in The Clay Bird. Pather Panchali captures wonderfully the life of a lower-middle class Bengali, Hindu family. In a very modest way, we tried to capture the life of a lower-middle class Bengali, Muslim family. To get a complete picture of all of Bengal, you need to see both these depictions together. Clay Bird alone would not represent all of Bengal, and as close as they are to me, I cannot portray Bengali, Hindu families and societies. Whether I am a practicing Muslim or not is a separate issue, but it is very important that I am a Muslim because I can reflect and portray with some accuracy the experience of growing up and living in the context of a Muslim, Bengali family.

You linger as well on the old architecture of the mosques and madrassahs, as well as the ghat that is adjacent to it. What does this architecture mean to you?

It is mostly very subjective - it is taken from my experience as a child and it reflects very much a child's way of looking at such architecture. From my tiny village I went to this town with wonderful but strange and overpowering architecture. It has stuck in my mind, this imposing architecture - which has at the same time its own beauty - perhaps because of the sharp contrast with the fluid, riverine village that I came from.

One of my earliest memories from the madrassah was of fog on the huge steps in front of the madrassah. As a little boy, the steps looked imposing and big, and the fog created a kind of mystery. At a subconscious level, while making the film, I probably wished to reproduce the architectural motifs and rituals from my childhood. The steps in the film were very similar to my actual madrassah. I sometimes made things difficult for my crew because I was obsessive about creating certain situations like the early, pre-dawn fog on the steps. It was not a Hollywood film where you could create fog; we had to wait three nights for the fog to appear! I remember returning to the madrassah from a rainy monsoon day and seeing this fog - the image was imprinted forever in my mind. I wanted to recreate that: the dark overcast sky, a little breeze, drizzling rain, and a flood of water. When my sister died, in fact, the next day, we could not find the grave anymore because it had become submerged under water. The architecture and the visuals that you see in the film come from all these personal memories.

To the unfamiliar, the repeated shots of the boys making ablutions at the ghat immediately brings to mind Benares on the ganga or Ganges, and the Hindu pilgrims who perform their ablutions there. Is this an association you sought to explore?

It was not a conscious association but that is the beauty of such shared symbols. The commonality is not only with Hindu religious rituals, but also with Christianity's baptism, the significance of water… There are other commonalities that have been referred to in the film. The story of Abraham's sacrifice, for example, is alluded to in the teacher whose name we kept as Ibrahim, a unifying factor for Judeo-Christianity and Islam - a gesture towards the concept of belonging to the same book shared by Islam, Christianity and Judaism. We generally only talk about the conflicts between religions but there are so many commonalities which are equally striking; they are basically the same thing with the façade of difference.

Given the massive brutality and genocide of the Pakistani military, your depiction of the military operation is, if anything, understated. Did you consciously make this choice?

I made that choice quite naturally. I am not sure why, but I cannot watch a film with the slightest blood, I cannot see a film with violence. We tried to create a sense of violence without literally showing it. You get the audience to feel it rather than actually showing it. It is such a stereotype that in any movie that has to do with war you show too much. The other thing is that it was a conscious choice to make a gentle film - the gentleness is the core of the film, an appeal for tolerance, harmony and peace. You cannot show it in a contradictory way by exposing violence.

There is another aspect of it: many films, if not all, made in Bangladesh to date on 1971 show in a more commercial, exploitative way, excessive violence, including rape. Such things have been shown so much. So Clay Bird is in a sense almost a natural reaction to this tendency, it stands in opposition to this excessive showing of atrocities and violence. We thought that it is not necessary to replicate the same tendency.

The genocide committed by the Pakistan Army is a war crime and that is very much expressed through the film and is condemned in the film too. That is important. We do not need to be graphic. That is what our contemporary media does: reproduces graphic violence. It is a vicious circle: in reality, there is violence, and the media reflects violence. This creates an insensitivity, a numbing of human sensation, this is why people do not care about what is happening in the world, about all this violence. It is important to show people being affected by violence, the devastating consequences it has. Whereas if you show violence itself, you may make people more violent, and we have tried to stay away from that.

The boatman in your film (who is also like a sadhu figure) makes a very interesting comment about the Qazi, Anu's father, that the Qazi in the film once used to dress like an Englishman, before he was, as it were, born again. What did you intend to suggest here, given that you do not really explore this transition in the film?

First of all this was very autobiographical. It comes from the story of my father. He studied in the most Western elite school in Calcutta - Presidency College - and he was more Western than Westerners, a self-declared atheist, a Hindustani classical vocalist from a very so-called secular, liberal, Westernized family.

This is the whole paradox: it is not madrassah-educated people who become fanatics. It is not half-literate madrassah students who become the most militant Islamists; it is the most Western-educated people who are becoming militant. This is not limited to Islam or Muslim societies; you see the same kind of thing in Christianity and Hinduism. More Western, educated people are becoming born-again Muslim or born-again Christian or born-again Hindu. Both my lived experience and the film reflect the fact that it is not traditional believers who become problematic but the born-again variety who do. You can find examples in Western countries too: new Christians (such as in the White House!) are much more militant.

Catherine Masud: In fact it is the madrassah-educated boy who becomes a filmmaker!

There is another similarity between the Qazi character and my father: I saw my father during and after the war going through a major transformation. He had this hard, solid belief which mellowed a lot over the years. Similarly, by the end of the film, the Qazi's naïve belief that Muslims cannot kill Muslims is completely shattered, devastated. This is exactly what happened to my father. He became so much less imposing, so mellow, so shaken in his beliefs that he withdrew me from the madrassah. He sent me to a regular school after that.

People mature from experience, from a deeper understanding of religion. When you know the least about faith, when you suddenly become religious, that is when you have this zeal and fervor, because you are relatively ignorant about the new ideology you have embraced. When you know more, you gain more wisdom, and that is what happens with the Qazi character in the film.

You mentioned this already and I wanted to ask you about it: Clay Bird has been compared to Satyajit Ray's Pather Panchali. How do you respond to this comparison?

It is a tradition to make conscious reference to another work of art, to pay tribute to another work of art in one's own. I wanted to tell a parallel story in a sense of a Bengali Muslim family, as I mentioned earlier. My film is a tribute to that great master, Satyajit Ray, and his work.

I am very proud to have my work compared to Satyajit Ray's, of course. It can also be used as shorthand for people to understand - if people know that my film is something like his, they have a way of understanding it. There is also a tribute, as I said - the simplicity is something I borrowed from Satyajit Ray, I am indebted to him. We tried to avoid pretentiousness, showiness: in the film there is no great acting, lighting, great spectacles. Nothing. It is a very simple, linear, under-told story.

In addition to this conscious effort to make reference to Pather Panchali, other things are coincidental. My personal life, for instance, is much closer to Pather Panchali than to Clay Bird. In Pather Panchali, Durga was older than Apu; in reality, Asma (the same name in the film as in real life) was my elder sister. But for scripting purposes, I made her younger.

I saw Pather Panchali for the first time - I was not able to watch any films during my time at the madrassah - when I was about 14 or 15 and it was one of the first films I had seen. I was taught in the madrassah that cinema was something horrible and vulgar with songs and dance, which is of course mostly true! So I had this antipathy against cinema. But when I saw Pather Panchali, one of my earliest films, it was incredible, something so close to my story. My relationship to my sister was very similar to what was shown in that film - she was always very active and restless, she loved nature, she wanted to go out all the time, and I was very coy, docile, very soft and gentle. The father was also like my father - a totally callous and oblivious male! The mother in the film not only keeps things running in the family, the whole struggle and burden is on her. That reminded me of my mother as well. And the craving for life, the zest for life that I saw in my sister is also there in Durga. Also the landscape, the festivities… I grew up with these beautiful, Bengali pagan festivities.

So it is also coincidental. But then again there is a major departure in our film, something that is not there in Pather Panchali (for obvious reasons) which is the theological dimension. Also, Clay Bird has as its backdrop the birth of a nation which is so interesting because it is not just the coming of age of the main character, but also of the nation. It is a film about a time, a nation, and also about a little boy and his family. So these things represent a bit of a departure from Pather Panchali.

Who else would you identify as influencing your work?

I am influenced and inspired by everything, every film I see! But definitely, among many, I am inspired by the simplicity and economy of both Abbas Kiarostami, the Iranian filmmaker, and of Ozu, the Japanese filmmaker. Any filmmaker who prefers simplicity impresses me. I am not into gimmicks or spectacles. And I am certainly not a fan of violence in film either!

What are you working on now? Do you plan to make another feature film?

Yes. We just finished shooting a new feature film called Anthar Jatra. We have not decided the English title yet, but the literal translation is "Inner Journey." Again, it is a story about a single mother and her son.

Thematically, it touches very contemporary phenomena, particularly issues of identity - complexity rather than crisis - of the generations being brought up outside their homelands (in England or in America). It is set in Bangladesh, where the mother and the boy happen to return after 15 years. Their soul-searching, their dislocation, their identity, all of that is explored.

The return for the mother is very complicated. She has been divorced and feels a lot of bitterness. Her ex-husband then dies and she has to return to Bangladesh to bring her son for the funeral. So it is a very complex return for her. And for the boy, it is like rediscovering his country.

So it is really about the questions confronted by the diaspora. It is a very important subject which has been addressed in literature and in cinema in other parts of the world. Since we spend a lot of time abroad, we went through some first-hand experience as well, so it is based on some actual stories.

It will hopefully be released by July this year.

Interview conducted by Nermeen Shaikh of Asia Society