Pandemics: Globalization Bites

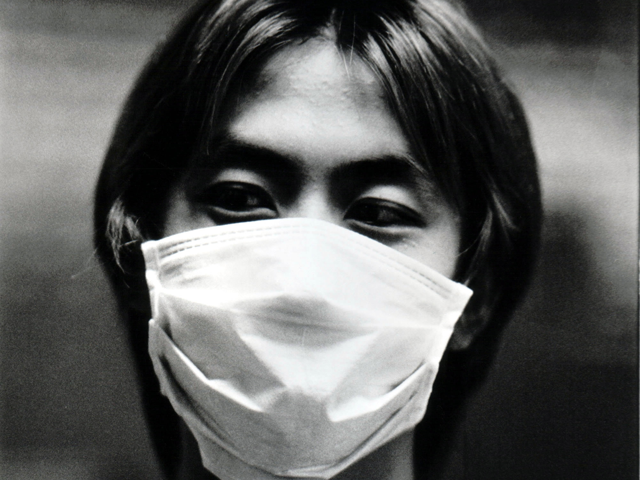

Microbes are masters of exploitation. Some attack in places of poverty. Others take advantage of emotions like fear and shame. Airborne illnesses freeload by hopping aboard jet travelers, which means a local outbreak can quickly become a global crisis. When an illness hitchhikes along global routes, it becomes a pandemic.

Today, advances in medicine can treat and even eradicate many sicknesses. Are the world’s healthcare systems strong enough to combat diseases that leap national and economic boundaries? Or is ensuring the health of others the surest way to protect oneself?

Since the April of 2009, H1NI, or "swine flu" has been alarming officials and parents, causing school closures, and forcing quarantines across the globe. People were especially worried that young children seemed to be more susceptible to the disease, and that the virus was similar to the one that caused the 1918 pandemic. The strain of flu spreads with ease between people, but has turned out to be milder than expected.

Health officials still are concerned about other known threats. Before H1N1 grabbed all the headlines, the biggest threat seemed to be the H5NI strain of Avian Influenza, or "bird flu," which was identified in Southeast Asia in 2004. By 2006 birds had infected people in Africa, the Middle East, and Europe. Health officials worry that the virus, which kills 50% of its victims, is mutating and may one day easily transmit from person to person.

Such a flu strain would probably appear on poultry farms in Vietnam or Indonesia, where farmers are too poor to take preventative measures like buying gloves to handle birds or destroying infected flocks. Yet early detection is critical in containing an outbreak that could spread across the globe. Many people say that boosting health systems for the underprivileged would be the surest way to prevent a global emergency.

Yet health care systems are already stretched thin by HIV/AIDS, which has infected 65 million people worldwide. There is not yet a cure, and although medicines can delay and minimize symptoms, these are expensive treatments for most of the world’s poor.

The AIDS virus spreads much more slowly than an airborne flu virus. Yet it has capitalized on human prejudice since it appeared in the 1980s. The lack of education for girls and low status of women in many countries increase their risk of contracting the virus. Local communities often discriminate against people living with HIV/AIDS and discourage patients from seeking care. Even national governments like China have denied that HIV/AIDS was widespread in their country, thinking that it was an immoral disease. They lost the chance for early prevention, instead inviting the disease to become entrenched.

Diabetes is another illness that is best battled through cultural approaches. Known as the "silent killer," it is caused by habits and genetics. The popularity of processed food has made people fatter as they consume more calories with fewer nutrients. By 2025, 330 million people could have Type 2 diabetes, 60% of them in the Asia Pacific region. While this used to be known as "adult onset diabetes," it is increasingly appearing among children and teens that live in urban areas, eat refined food, and have sedentary lifestyles.

Diabetes is especially worrisome as it causes blindness, kidney failure, heart disease and the loss of limbs in people who should be at the prime of their working lives. And because diabetes is chronic with no cure, it is costly to manage. A poor family in India with a diabetic will spend 25% of their income controlling the disease.

Pandemics have changed the course of history many times. The "Black Death" traveled from Asia to Europe along the Silk Roads and obliterated up to a third of infected populations. Smallpox, brought by Europeans to the Americas, killed up to 95% of Native Americans. The 1918 global flu pandemic killed tens of millions.

HIN1 and H5N1 flus, HIV/AIDS, and diabetes have all appeared in poor areas where healthcare is limited. Like many diseases without a cure, they are best prevented through education. If you have access to hospitals, doctors, and medicine, does that mean you will be safe from these threats? Or, could it be that promoting health awareness and education is the surest means of protecting yourself?

Author: Heather Clydesdale