Japanese Internment Survivors Warn Against Repeating History's Mistakes

Demonstrators at Miami International Airport protest an executive order that President Donald Trump signed clamping down on refugee admissions and temporarily restricting travelers from seven predominantly Muslim countries on January 29, 2017. (Joe Raedle/Getty)

In the days after the September 11 terror attacks, President George W. Bush, disturbed by reports of hate crimes toward Muslims, turned to his secretary of transportation at a cabinet meeting. "We know what happened to Norm Mineta in the 1940s, and we're not going to let that happen again," he reportedly said.

Mineta had been among the roughly 120,000 people sent to internment camps across the United States during World War II without due process for no reason other than their Japanese ancestry. Ten years old when he and his family were taken from their California home, Mineta spent years in a shoddily constructed Wyoming facility under armed guard. As a Cabinet secretary six decades later, he said he drew on that experience when he decreed that there should be no racial profiling at airports.

Mineta’s position echoed that of his boss. Six days after the 9/11 attacks, President Bush sought to draw a clear distinction between Muslims and the terrorists who had attacked America. While visiting a mosque in Washington, he said that “Islam is peace” and the targeting of Muslims “should not and that will not stand in America.”

The current American president, however, has signaled a markedly different approach. Last week, Donald Trump signed an executive order restricting entry to the United States by people from seven predominantly Muslim countries — an order ostensibly intended to protect against terrorism. During his campaign, Trump called for a “total and complete shutdown” of Muslims entering the United States and floated the idea of registering Muslims in the country into a national database.

Amid sizable public support for these policies, and as anti-Muslim hate crimes have returned to their highest levels since 2001, survivors and historians of Japanese internment are saying that lessons from that episode of American history seem to have been forgotten.

“As a college instructor, I still find that my students’ knowledge is limited,” Abbie Grubb, a lecturer of history at San Jacinto College in Houston who researches public remembering of Japanese internment, told Asia Society. “Usually about a third of them don't know anything about what happened. … By-and-large, it's still not something that's well-recognized.”

In the aftermath of the Pearl Harbor attacks, President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed an executive order opening the door for military commanders to relocate people deemed security risks to “military areas.” Japanese and Japanese Americans on the West Coast were then rounded up and sent to internment camps around the country that often had overcrowded and poorly maintained living quarters.

The move had wide support among a nervous wartime public in the region, but it was also popular among whites who resented competition from Japanese laborers. “We're charged with wanting to get rid of the Japs for selfish reasons,” the managing secretary of a farming association was quoted as saying at the time. “We might as well be honest. We do.” Another member of the group wrote to his congressman: “The Japanese cannot be assimilated as the white race [and] we must do everything we can to stop them now as we have a golden opportunity now and may never have it again.”

A young Japanese American named Fred Korematsu refused to enter the camps in 1942 and was subsequently arrested. His legal challenge wound its way to the Supreme Court, which, despite the blatant absence of due process, ruled against him and upheld the legality of internment. The camps remained open for the duration of the war and destroyed the lives of many of the detainees who had lost their property, jobs, and communities. It wasn’t until the 1980s that the U.S. government formally admitted that internment had been a mistake.

However, in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, there were calls to use Japanese internment not as a cautionary tale, but as a precedent in support of profiling Muslims. A book titled In Defense of Internment: The Case for Racial Profiling in World War II and the War on Terror garnered wide attention by arguing that internment had been justified. The author, conservative pundit Michelle Malkin, even chastised Norman Mineta for “milking his childhood experience at a relocation camp as an excuse to ban profiling at airports.”

Actor George Takei shares a personal story from his childhood where stereotyping landed his family in internment camps. (6 min., 8 sec.)

Fred Korematsu, 85-years-old by that time, published an essay in response to the book. “Fears and prejudices directed against minority communities are too easy to evoke and exaggerate, often to serve the political agendas of those who promote those fears,” he wrote. “I know what it is like to be at the other end of such scapegoating and how difficult it is to clear one's name after unjustified suspicions are endorsed as fact by the government.”

But today, parallels between the Japanese American experience in World War II and Muslim profiling are resurfacing. After Donald Trump’s call to ban Muslim entry to the United States in late 2015, a reporter asked the then-candidate if he would have supported Japanese internment. “I would have had to be there at the time to tell you,” he replied. The following year, a spokesman for a Trump-supporting Super PAC cited Japanese internment as a precedent for creating a registry for Muslim immigrants.

Just as after 9/11, prominent Japanese Americans have again stepped up to use the internment experience as a cautionary tale against policies targeting Muslims. Writing in the Washington Post in November, 79-year-old actor and internment survivor George Takei said, “It begins with profiling and with registries … In [Trump’s] world, national security justifies actions that are ‘sometimes not right,’ and no one really can guarantee where it will end.”

Days later, Norman Mineta once again invoked his wartime experience. “In the decades that have passed, Americans said that it would never happen again,” he wrote. “We would never let hatred and fear blind us to our shared humanity. We prided ourselves on having evolved beyond such impulses that would make us discriminate against an entire population based on where they came from, how they looked, or how they prayed. To our great sadness, we are seeing these chilling ideas creeping back into normal discourse around the world.”

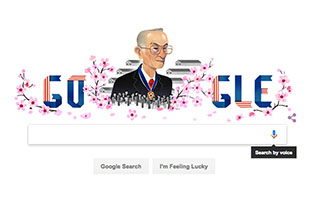

Congressman Mark Takano, whose parents and grandparents were sent to the camps, responded on Monday to President Trump’s executive order by telling his fellow lawmakers: “If you are silent today, you would have been silent then.” Even Google appeared to draw the connection on Tuesday when it featured Fred Korematsu on its homepage.

Will these reminders be heeded? Abbie Grubb said that while education about Japanese internment has improved significantly in the United States in recent years, it’s still far from sufficient. “In textbooks, it often gets one of those sidebar-style mentions,” she said. “But it's still seen as a tiny blip in comparison to the bigger spectrum of U.S. history. I think some people see it as only important if you’re Asian American, but it's much more important in the broader story.”

She said that when she teaches her students about Japanese internment, they’re most often curious about how it was able to happen. “One of the things that I emphasize is the fact that this was unconstitutional, and when things like this happen, it's incumbent not just on all three branches of government to recognize that, but for people to oppose it,” she said. “There was opposition to internment during the war years, but it was pretty minimal.”

“When you hear [Japanese interment] being discussed at such high levels as a precedent, I think it should serve as a warning,” she added. “It is a call for education and awareness to make sure people do know what happened. … This is not a precedent for the United States to follow.”