Interview: What It Was Like to Photograph the 'Shabby, Squalid Dignity' of the Kowloon Walled City

For five years starting in 1987, Canadian photojournalist Greg Girard and British architectural photographer Ian Lambot teamed up to photograph Kowloon Walled City, the famed enclave in Hong Kong which was one of the densest settlements in the world until its demolition in 1993. Originally a Chinese fort, the Walled City became a crowded residential dwelling after the occupation of Hong Kong by the British, who largely adopted a “hands-off” attitude to the structure. Asia Blog caught up with Girard and Lambot over email following their appearance last month at Asia Society Hong Kong’s “Revisiting Kowloon Walled City” event on November 7, 2013.

Asia Society: How did you start photographing the Kowloon Walled City?

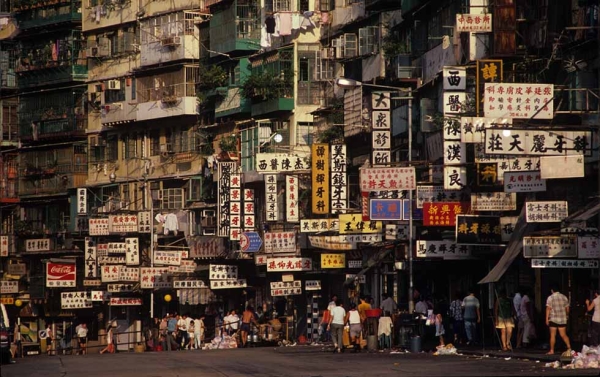

Greg Girard: I "discovered" it one night in 1986 while photographing in the streets in Kowloon City near Kai Tak airport. I had heard of the place but never went deliberately looking for it. But on that night I walked around a corner and saw this mutant building, illuminated from the lights of its apartments. It was unlike anything I had ever seen. It wasn't exactly one building, but it wasn't separate buildings either. It was a glowing agglomeration of buildings joined and piled together. A sort of medieval science fiction-like thing that was astonishing to find in modern Hong Kong.

Little by little I started visiting, and began trying to photograph this very unusual community, and its living and working spaces.

Ian Lambot: The Walled City was just one of many unusual parts of HK I was finding on my exploratory walks through the city in those days. In many ways, the Walled City, at least from the outside, did not look so different to many of those older parts of HK, especially in the early 1980s when it was still surrounded by the large and well-established squatter settlement there.

I had heard the stories about the place but it was only when the clearance was announced in January 1987 that I started to think about going out there and taking another look. And by then, of course, things had changed quite dramatically. The surrounding area was being developed and becoming smarter by the day and the squatter settlement had been cleared away, so the Walled City was standing there alone in its shabby, almost squalid dignity. As an architect and an architectural photographer, I was immediately hooked and decided I would return and start photographing there, still at this stage very much for my own amusement.

My modus operand as an architectural photographer has always been to start at a distance, circling the building and trying to work out when the light might be best at different times of day. After a few establishing shots, I then move in closer to see what details or part views I might find.

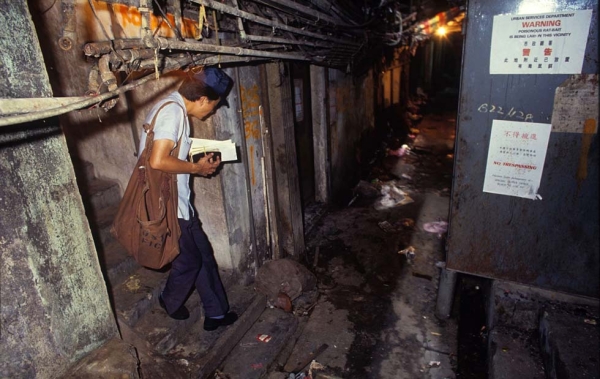

Over time, I was closing in on the subject. I started making forays down the various alleys, the larger more clearly defined ones to begin with, then the smaller and more remote, and then the various staircases. And so now I was photographing inside the City and out and finding myself ever more captivated by what I was finding.

What was it like to go inside?

Girard: In the beginning, before the announcement in 1987 that the Walled City was going to be demolished, there was a lot of hostility. Anything in the media about the Walled City at that time was mostly sensationalist and exploitative, about how miserable, dangerous and dirty the place was. So people were giving you the evil eye and slamming doors if you were walking around with a camera at that time. You can hardly blame them. Little by little I started making some progress but things changed considerably after the announcement about the demolition and relocation. It got easier as people understood that the place's days were numbered.

I would catch the airport express bus in Central and take it to Kai Tak airport and then walk the four blocks or so to the Walled City. I might have photographed someone on an earlier visit and made prints to give to them, so I would start by going to see them and giving them the prints. That might lead to being introduced to someone else, a neighbouring home or business, and so a new door might open. Or I would just start wandering around and seeing if I could get into some new place. Or I might just photograph in the public spaces: the alleys, the shop exteriors, the rooftops or stairways. There was always some new picture to make.

Lambot: By the nature of the place, doors to premises were frequently wide open, allowing you to wander in to all sorts of locations normally out of bounds – shops, clinics, schools and factories. Strangely, this proved to be remarkably easy as most people were more baffled why I might be interested their unkempt premises, than offended in any way. And I only ever remember one place that specifically said no.

Despite all the stories of the Triads and drugs, I had seen almost no evidence of this while I was in the City, and anyway it wasn’t something I was interested in. I wanted to concentrate on the ordinary people and the places they lived and worked in, on just why this extraordinary community seemed not just to survive but thrive. Despite the conditions, nearly everyone seemed to be happy living or working there. How could this be explained?

What was beginning to fascinate me more and more about the City, though, was not so much the architecture as the people living there, just how it managed to work when everything in my architectural training had told me that that many people couldn’t possibly live in such close confines and manage to build a community.

Girard: I have to say that it never actually felt crowded in the Walled City. The alleys were never crowded, though there was constant traffic and activity. And living space was tight, but not as reduced as we see in Hong Kong today with people living in cubicles or box-like sleeping spaces. Many apartments did however lack windows that opened into air or light, and this is where the reduction of space was noticeable. Not the living space per se but the space around the living space. There often wasn't any. So, for most people, the journey from the front door of your home to the first sight of natural light usually involved a walk down several floors of stairs and then along a series of alleys before emerging into the light of day, or night.

So what insights did you take away about the Walled City’s architecture?

Lambot: Two things spring to mind. The first is how the proximity of life, work and leisure creates a community. All too often architects and planners want to separate aspects of life, living here, offices there, factories somewhere else. I don’t think this is right and, thankfully, neither do a number of other people nowadays. Hong Kong has always allowed this mixture, but it disappeared in Europe and is only now making a comeback with mixed-use buildings and a more flexible approach to planning.

The other aspect was summed up by Aaron Tan at the talk when he described the City as an inorganic object that has grown organically. This is much more difficult to create as, by its very nature, it is spontaneous. A need is seen and it is instantly answered by some strange form of common consent. Places where people meet and interact form naturally, not where the architect thinks it should, but in anonymous spaces where people actually want to. Such ideas and flexibility have been appearing more and more in office planning, but on a bigger scale it is much harder to implement, though some architects are exploring what might be possible.

How have you seen Hong Kong change over time?

Lambot: What is difficult to remember now is just how different HK was 35 years ago. I arrived in 1979, when large parts of the City were still living in third-world standards. But what really caught my imagination and led me stay was the extraordinary rate of change. The city was evolving almost literally before your eyes, both in size and sophistication. It was an exciting place to be.

Girard: Every city goes through its own evolution in its own way. Hong Kong now has an appreciation of its history that it didn't have when I was photographing in the 1980s. If the Walled City had somehow remained standing until today we would have dozens of films and books about the place, with more people arriving by the day to study it or simply experience it. At the same time, I find many of the traces of the Walled City in the 5 and 6 story walk-up buildings of Kowloon City in the surrounding neighbourhood: the metal grill work on the doors and mailboxes, the use of the spaces between the buildings, the illegal rooftop additions, et cetera. But these too are disappearing, as I saw on a visit in November of 2013. Many of the buildings are shuttered and will soon be demolished.

What insights did you gain about photography?

Lambot: What can I say? I come from an older tradition where the image captured on film is everything – carefully composed, thoughtful and, above all, honest. It is very much what I still enjoy when taking pictures with a 4 x 5 camera – thinking about the picture and taking my time.

Girard: As much as we know that photography isn't reality it's still the best tool we have for recording our reality.

If you could go back in time to the Walled City with one roll of film, what would you photograph?

Lambot: If I could go back and photograph again, it wouldn’t be a roll of film, but a box of 4 x 5 transparency film and the time and patience to try and photograph some of those alleys and stairways on the large format camera. A few shots like that would be priceless.

Girard: The Cathay Pacific stewardess who I saw, in uniform, one day walk into the Walled City pulling a suitcase, probably returning home after a flight. At the time I raced to follow her to try and make a picture but she disappeared into the maze of alleys before I found her and I never saw her again.