Interview: Evan Osnos on Xi's Biggest Puzzle and 'Acute Dumpling Withdrawal'

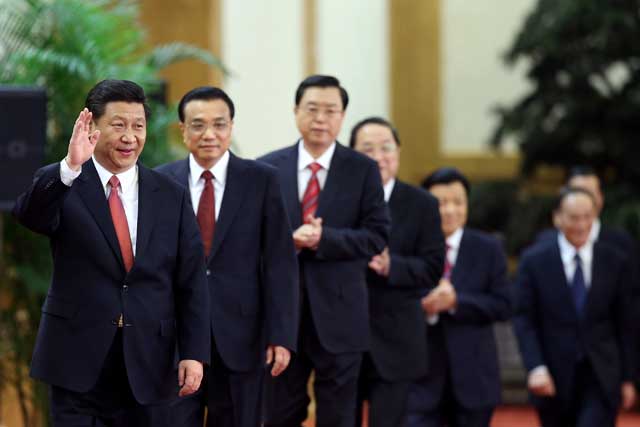

L to R: Members of the Politburo Standing Committee Xi Jinping, Li Keqiang, Zhang Dejiang, Yu Zhengsheng, Liu Yunshan, Wang Qishan and Zhang Gaoli in Beijing on Nov. 15, 2012, the day China's ruling Communist Party revealed the new Politburo Standing Committee. (Feng Li/Getty Images)

Evan Osnos joined The New Yorker as a staff writer in 2008 and is now a correspondent in Washington, D.C. who writes about politics and foreign affairs. His forthcoming book about China's rise (Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2014) is based on eight years of living in Beijing. Previously, he worked as the Beijing bureau chief of The Chicago Tribune, where he contributed to a series that won the 2008 Pulitzer Prize for investigative reporting. He has received Asia Society's Osborn Elliott Prize for Excellence in Journalism on Asia, the Livingston Award for Young Journalists, and a Mirror Award for profile-writing. He has also worked as a contributor to This American Life and a correspondent for the public television series Frontline/World. Before his appointment in China, he worked in the Middle East, reporting mostly from Iraq.

Osnos will share his views of China's current leadership at Asia Society New York this Thursday, November 7, in the panel discussion "China, One Year Later." Joining Osnos for the discussion are Arthur Ross Director of Asia Society's Center on U.S.-China Relations Orville Schell; former U.S. Ambassador to China J. Stapleton Roy; and Dr. Susan Shirk of the University of California, San Diego.

For those who can't attend the panel in person, a free live webcast will be streamed at asiasociety.org/live at 6:30 pm New York time. Online viewers are encouraged to submit questions before and during the program to [email protected] or via Twitter or Facebook using the hashtag #askasia.

AsiaBlog reached out to Osnos ahead of Thursday's panel for a preview of his take on the Xi Jinping era, one year in, and to learn more about his recent career transition.

You left China this past summer after eight years. How is the transition going? What have you been up to?

You left China this past summer after eight years. How is the transition going? What have you been up to?

The transition has been fascinating. It's not easy packing up a life in China after so many years, but we were ready for a new set of questions to mull over, a new list of books to read. My wife Sarabeth and I arrived in Washington this summer, and, after a couple of final months of book leave, I went back to work at the New Yorker on October 1st, which happened to be the day the government shut down, though I see no correlation. China will still be one of my subjects, of course, but I'm also enjoying the process of learning a new language, in a sense: U.S. politics, national issues, and the things that happened in the decade I was away.

Someday I'll try to write about this transition in detail, but for now I can say that the experience of going from the capital of the world's rising power to the capital of the world's incumbent power has been memorable.

In your last interview with Asia Society, you mentioned one of the problems facing the Chinese government and the party was an inability to absorb the demands of a nation which has begun to articulate individual desires and hopes. With so much resting on Xi's ability to deliver the "Chinese Dream," what structural steps do you see being taken to accommodate this new wave of heightened expectations? Are you optimistic they'll be implemented successfully?

The problem of expectations is arguably the greatest puzzle facing Xi Jinping and his generation of leaders. Everything about their political language and body language indicates that they recognize what they are facing, even if they don't know how to solve it. They are trying to figure how they can satisfy their public without undermining the economic and political basis of their authority. In his first speech, Xi acknowledged that people "hope for better education, more stable jobs, more satisfactory incomes, more reliable social guarantees, higher-level medical and health services, more comfortable living conditions, a more beautiful environment, and they hope that their children can grow up better, work better and live better." It's a hell of a list.

Since then, the leadership has promised what Xi calls a "profound revolution" — which will, presumably, encompass elements of land reform and steps to boost the lowest incomes and allow depositors to earn more on their savings. His government has promised to address the environmental crisis, though the steps it has taken have received mixed reviews. Xi may yet surprise us, but so far he has not given any indication that he is prepared to make comprehensive reforms.

Chinese national identity is often played out in vacillations between shame and pride: shame in the "humiliation" of the colonial past and pride in regained stability and international stature. These are powerful emotions which have provided a lot of the momentum for leaders' regimes since at least Mao. Does the Party have the political goodwill to continue harnessing this dynamic to fulfill its policy goals?

This is not an easy strategy to deploy successfully. The Party has raised a generation of young people to believe that China deserves to be respected, and those who do bring dishonor upon it must be criticized. But what happens when dishonor begins at home? What happens when Chinese officials are contributing to humiliation rather than preventing it? Chinese young people put their pride in the nation, not the Party, and that makes for a volatile well of emotion.

The past year has been relatively quiet for China in terms of international disagreements, compared to the disastrous final days of the Hu administration, which saw virtually every neighboring country inflamed over territorial disputes. Does this signal a change of approach for Chinese foreign policy? What does the next year hold in store for China's relationships abroad?

I don't think it signals a change of approach. The trend of the past year is probably not distinct enough to indicate a strategic shift. Over the past five or ten years, China is demonstrably more vocal about the South China Sea and the East China Sea. Is this a precursor of conflict to come? I'm not sure — and I'm not convinced that Chinese leaders know the answers.

China is conflicted already: It does not seek to be portrayed or perceived as a hegemon, but it has very little ability to accept policies at odds with its objectives. This creates the conditions for further tension.

Last question, from one former Beijing laowai to another: what food do you find yourself missing most now that you've moved back stateside?

I am in a state of acute dumpling withdrawal.