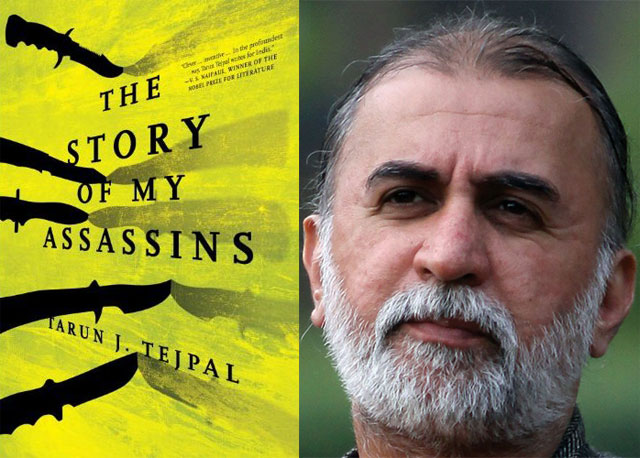

Book Excerpt: 'The Story of My Assassins' by Tarun Tejpal

Tarun Tejpal (R), author of 'The Story of My Assassins.' (Shailendra Pandey)

The third novel by Indian journalist, publisher, and author Tarun Tejpal, The Story of My Assassins is the story of a journalist who learns that the police have captured five hit men on their way to kill him. Upending his comfortable life, the revelation prompts him to launch an urgent investigation into the lives of his would-be killers — a ragtag group of street thugs and village waifs — while also forcing him to reexamine his own life, too — to confront his own complex feelings about the country that spawned the hit men, as well as himself, his job, and his treatment of the women in his life.

Tejpal will read from and discuss his new novel at Asia Society New York on Thursday, October 4.

The public prosecutor — a balding clerkish-looking man like my father, but with the alert eyes of a shopkeeper — said to me, "Do you know these men?"

I looked at them. Four of them lowered their eyes. The brain-curry man looked at me as if I was the accused. "No, I don't."

The swirl in the courtroom seemed to have stilled a bit. "Do you know that there has been an attempt to kill you?" "Yes, I do."

"Do you live under twenty-four-hour police protection?" "Yes, I do." "Do you know who would want to have you killed?" "No, I don't."

"But do you agree you may have enemies, people you have offended or harmed by your work, who may want to get rid of you?"

"Yes, sure, it's possible."

"You have no reason to believe that these men may not be the contracted killers?"

"No, I don't."

Yoronour gave me a grave, pasty look as if I had said something of profound importance. Someone really should have stuck a beard on his chin.

The lawyer for the defence, more a little sparrow than a penguin, in an oversized shabby black coat and an old-fashioned pencil moustache, said, waving his arm in a cultivated flourish, "Look at them very carefully. Do you know any of them?"

"No sir, I don't."

"I repeat — look at them again. Very carefully. Have you ever seen these men?"

I actually did what he asked, scanning their faces slowly. The policeman holding the wrist of the one on the extreme left yanked his face up — prominent cheekbones, a big nose, black stubble — and the other three put up theirs in instant reflex. They looked like each other. Everymen. The roads, bazaars, offices of India were full of men like them. Nameless men who did faceless jobs and perished unmarked in train accidents, fires, floods, epidemics, terrorist blasts, riots. At best, statistical fodder. But I also knew this was how criminals really looked, not like the stylized stars that the movies everywhere in the world loved to essay. More criminals fashioned themselves on film stereotypes than the other way around. Of the five, only brain-curry man was a serious student of cinema.

I said, "No sir, I haven't."

Actually I could have seen them all my life and not remembered.

The tiny lawyer said in a forcefully mannered voice, "Tell me, were you at all aware that someone wanted you killed?"

Clearly this little semicolon of a man had also fashioned himself from cinema. Everybody in this damn country was an imitation of a Hindi film character. He stroked the lapels of his oversized coat, and worked his mouth fully, the pencil moustache mesmeric. I could see him — a wimp in school, a wimp as a son, a wimp as a husband, a wimp as a father, but in the courtroom the master of the moment.

"No, I wasn't."

"Was there any indication of a threat at all? A phone call, a letter, some rumour, a friendly remark — from a colleague, a source?"

"No sir, not really."

"But you were under police protection?"

"I was."

"Since when?"

"The last few months."

"Why?"

"I don't really know. I was not told anything."

"You were not told anything. Of course you were not told anything. Who put you under police protection?"

"The government, the police department... the intelligence bureau... the sub-inspector arrived with his men the day the news broke, and I was just told that I needed to be under protection."

"You were told, you were told, in the way the police tells us all kinds of things. You were told. And you didn't bother to ask why, to question what you were told? You just believed what you were told. By the same police that you keep exposing for its lies, its human rights violations, its abuses and its excesses! Such a fine journalist, yoronour! We all respect his work. Fighting against corruption, fighting the government's wrongdoing, the police's wrongdoing, standing up for society. But this time you believed the police. You believed it was telling the truth — which I am sure it was, I am sure it was. Even the police tell the truth sometimes. So you believed everything the police told you?"

Sethiji's smile was getting a little rigid. Yoronour seemed to have started some other consultations on the side with his clerk and another penguin. Sara was looking as ferocious as the brain-curry man. Together they could have dismembered me in minutes, he making a hole in my skull and she uprooting my tool.

"No. I didn't believe or disbelieve. I just let them go ahead and do their job."

"Good. That's good.The police must be always left alone to do their job. Even by investigative journalists. So can we say you trust the police?"

"No, I wouldn't go as far as to say that."

"So mostly you wouldn't trust them, but in this particular case you did?"

"Well, yes. As I said, I just left them alone to do their job."

"Let us be hypothetical. Do you like hypothesis? I am told all journalists like hypothesis. Do you?"

"Sure."

"Let us hypothetically say the police wanted to fix some innocent fellows. For whatever reasons, personal, political, pecuniary, whatever. This police that you mostly don't trust. So this police charged them with trying to kill you, gave you police protection and locked them up. Of course the police would never do something like this. We are only trying to form a hypothesis.

Fuck, was Sara part of his defence team?

From The Story of My Assassins by Tarun Tejpal. Copyright © by the author and reprinted by permission of Melville House.