Sheridan Prasso: Seeing Past the Stereotypes

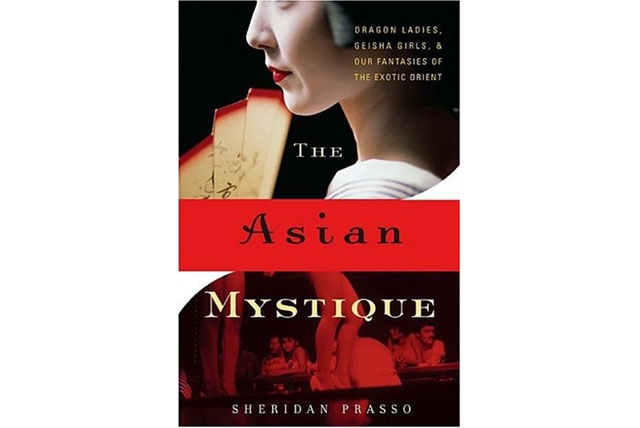

Sheridan Prasso's book The Asian Mystique lays out a provocative challenge to see Asia and its diverse people honestly, with unclouded, de-eroticized eyes. It traces the origins of Western stereotypes in history and in Hollywood, examines the phenomenon of "yellow fever," then goes on a reality tour of Asia's go-go bars, middle-class homes, college campuses, business districts, and corridors of power, providing intimate profiles of women's lives and vivid portraits of the human side of an Asia we usually mythologize beyond recognition.

Prasso has been writing about Asia for more than fifteen years, most recently as Asia Editor and a Senior News Editor for Business Week. Her articles have appeared in Time, The New Yorker, The New Republic, The New York Times, The Los Angeles Times, and other publications. She also is an advisor to the Asia Society's Social Issues Programs and a member of the Council on Foreign Relations and the National Committee on U.S.-China Relations.

Asia Society spoke with Prasso about her observations while writing her book and the need for perceptions of Asia to change.

You write about the way Asia and Asian people are portrayed in Western culture. Where do these perceptions come from?

When you grow up in America, you are subjected to images in Hollywood and on TV that present Asians in stereotyped ways, if you see them at all. You read about “exotic” Asia in travel writing and literature. These perceptions are deep-rooted in history, and trace as far back as Marco Polo and even the ancient Greeks. Often the impact of such images and impressions are subconscious and we don’t realize we have them. Asian Americans are also subject to them. In Asia, I sometimes meet Asian American men thinking that they can go to Asia and find a more “traditional” wife than the Asian American women they are meeting here – someone less career-oriented and more like their grandmothers. Actually, my grandmother of European origin didn’t have a career, and she also waited on my grandfather as a happy homemaker. There’s not much difference in these aspects of “traditional” in Europe and Asia, but instead these differences are generational and a matter of economic development. Women in the developed cities of Asia today are every bit as “modern” as women in America, if you want to look at it in those terms. But because of the myths created by our images, the ideal of the perfect Asian wife persists, and the ideas of Asia as exotic, sensual and decadent persist, too.

After writing about Asia for so many years, what do you think are the worst consequences of having the kinds of misperceptions you describe in the book?

The filter of “Asian Mystique,” clouded with so many issues of race and sex, blinds people to the realities of Asia and indulges Western fantasies such as the exoticism and "conquerability" of Asia. The implications of this are enormous and far-reaching, creating stereotypes that affect: Asian Americans in the workplace; cross-cultural relationships; business negotiations; and even East-West relations and foreign policy. It is difficult to sum up in a paragraph the magnitude of these misperceptions, because I dedicate hundreds of pages of my book to spelling them out, but I argue that we can never really understand Asian countries and correctly read situations until we rid ourselves of “Asian Mystique,” or at least see it for what it is – the elephant in the living room that affects in some way nearly every interaction between East and West.

Do you think that as a non-Asian woman, you were able to provide a unique perspective on this issue?

A man could not have written this book. Lots of Western men in the past have written about Asia extolling its beauties and glorifying its exoticism. As a woman, I offer a fresh, more real perspective on Asia. Because I am female, women invited me into their homes and shared their lives with me. They may not have been able to speak as openly and in the same ways with a man due to cultural mores. Plus, being a Westerner means that I can observe situations and relationships in a more objective way. After researching the history of stereotypes of Asians in Western culture, I think that if I were Asian myself I might feel too angry at all the injustices that have been done and the stereotypes that continue to this day. But as a non-Asian journalist with an anthropological background, I am able to write about them with a more objective eye.

The Japanese geisha is one of the most popular images in Western media of a subservient Asian woman. You talked with Mineko Iwasaki, the inspiration for the character in the 1997 novel by Arthur Golden, Memoirs of a Geisha. After talking with her and other geishas, what misconception about geishas would you most like to correct?

Ms. Iwasaki and the other geisha I spoke with feel that the Memoirs of a Geisha misrepresented the geisha world in very serious and damaging ways. After all, Golden’s book was essentially a Cinderella story – very much an American fairy tale – using Japan as its backdrop, and the story of a geisha as the young Cinderella with an undying love for her handsome prince. This story is completely unrecognizable to anyone who knows Japan or has met and talked with geisha. I encourage people to read my account of what they would like to correct and decide for themselves – particularly with the movie version produced by Steven Spielberg and starring a Chinese woman playing a geisha set for release this December!

The second part of your book takes a "reality tour through Asia using the icons of our stereotypes - geisha, housewives, exotic Cathay Girls, China Dolls, Suzie Wongs, Madame Butterflies, powerful Dragon Ladies, martial arts mistresses, and the like." What were some of the more striking lessons you learned from this "reality tour"?

There are fascinating aspects of how the “Asian Mystique” plays out all over Asia. In Okinawa, for example, there are girls who spend time under tanning lights and kink their hair like Beyonce in order to attract African-American Marines on the military bases there, and they specifically want to meet black men, not white. The reasons why are intriguing, and what happens to these modern-day “Madame Butterflies” years later after many are abandoned with biracial children is surprising, too. In another example, in the discussions I had with bar girls in Thailand, I wondered what attraction, if any, a young prostitute might have for an older, balding, pot-bellied Western guy. Is it just economics? Their answers surprised me: in rural Thai culture, a pot belly is a sign of prosperity, so there’s an aspect of pride in bringing a big old foreign guy home that plays into the attraction. The reality is much more complicated than how it may appear when you see these couples holding hands on the streets of Bangkok. There are quite a few such surprises at the nexus of these interactions around the region.

As you point out in your book, there is a strong sexual element to "The Asian Mystique." You talked with many Asian women at bars and nightclubs in Thailand, the Philippines, and Indonesia. What are ways of battling these sexual stereotypes when some of these women do seek foreign men to escape economic situations, and play into sexual stereotypes to enable this?

I think awareness is key. There is no such thing as an “Asian” woman with a prescribed set of behaviors and actions. As I try to illustrate in the second half of my book which I subtitle with a Japanese expression “Junin Toiro” or “Ten People, Ten Colors,” every woman is an individual. There may be cultural practices or beliefs that have come out of growing up in, say, Thai or Philippine or Indonesian cultures, but fundamentally all women, everywhere in the world, have more in common than the filter of “Asian Mystique” would have us realize.

At the root of many of these exotic images there is the fantasy that Asian women want to be rescued by Western men, as seen in the most famous stories "Madame Butterfly" and "Miss Saigon." You interviewed many women in Asia who clearly have no interest or need to be rescued by Western men. Do you feel this fantasy is an effect of larger global relations between Western and Asian countries?

There is a patronizing, missionary aspect to America’s foreign policy toward Asia, just as there is an aspect of “saving” the poor Asian girl (prostitute, war victim) from economic circumstances, life of prostitution, or “oppressive” cultural practices which we see in so many of our fictional stories about Asia – and played out in real life. The West needs to start treating Asian countries and Asian leaders – and Asian people – as equal partners. The danger is that otherwise, as Asia’s economic power continues to grow, Asian leaders feel pressed to “stand up” to America to prove their mantle and equitable position in the region, creating potentially dangerous security situations. We have seen how underestimating the military prowess resulted in surprising losses in the Korean War and the Vietnam War. We didn’t win either of those wars, but our attitudes have not changed: we see them played out in Hollywood all the time in such scenes as in Kill Bill, where Uma Thurman vanquishes the phalanxes of incompetent karate-chopping Asian males. I see all these cultural references as metaphors for how we in the West deal with Asia, and again think they play a subconscious role that affects our relations.

In the chapter "Power Women" you interview many Asian female leaders who have defied images of weak, submissive Asian women. But you also observe that they too are undermined by Western stereotypes. Did they feel this was an important issue for them to battle?

The reality is that Asia has had more women leaders in politics than America has. Asia was the first region in the world to elect a woman as head of government, back in the 1960s. The Philippines has had two women presidents already, and there are more Philippine women representing that country as ambassadors than there are American women representing America. And yet when we think about “Filipinas” we tend to think of maids, mail order brides, and nurses, rather than presidents and ambassadors! That we don’t recognize the powerful roles played by women in politics and leadership positions in Asia is testament to our stereotypes about Asian women. How can they battle it? We need to change our perceptions.

You also discuss briefly how the "Asian Mystique" affects Asian Americans, particularly fetishes among white, male Americans for Asian American women. These stereotypes have no relation to many Asian American women - or to women in Asia itself in fact - who were born and raised in the U.S. How has the Asian American community responded to your book?

The response has been tremendous. David Henry Hwang, author of M Butterfly, was one of the book’s earliest and most enthusiastic endorsers, and I frequently receive emails from Asian Americans –both men and women– who are thrilled that someone has finally written a book like this that’s for sale on the front tables of Barnes & Noble. Of course all Asian Americans know about these issues, but many Americans don’t: It has simply never occurred to them that “model minority” might be patronizing, or thinking that all Asians are good at math and the violin is a limiting stereotype. Several bloggers as well as websites, including modelminority.com, have written positively about the book in an attempt to get the word out. As I mentioned previously, I think it takes an outsider who grew up watching the images of Western culture to put a book together in this way, pulling together the issues that all Asian Americans, no matter whether they are of Chinese, Japanese, Korean, Vietnamese, Philippine or other Asian origin, must face as a result of stereotyping and explaining where they come from and why they persist.

My hope is that as this book continues to be embraced by the Asian American community, it will prove to the publishing industry that there is a large commercial market for this topic, and that will open the way for Asian Americans to publish more of their stories and experiences for the mass market commercial press.

You argue that "demand creates supply" and so the more educated we are about this "Asian Mystique" the less it will be offered to us. The media clearly plays a key role in perpetuating these exotic images of Asia. There has certainly been progress, but in what ways can the news, entertainment, and publishing industries engage consumers to want to see more sides of Asia?

More, more, more. More stories about the realities of Asia, and fewer about the exotic nature of travel and adventure and the “Wild, Wild East.” There is a real craving for knowledge about what’s going on in Asia today, and the media –of which I am a part— is not satisfying it, but instead offering stories that continue to play into our preconceived expectations. The desire is there; now if only editors would realize the need to fulfill it.

Interview conducted by Cindy Yoon of Asia Society.