New Report | Beijing’s Struggle to Control Religious Ferment

June 5, 2024 — Asia Society Policy Institute’s Center for China Analysis (CCA) has published a paper entitled Beijing’s Struggle to Control Religious Ferment, authored by CCA Fellow on Chinese Political Economy and Society G.A. Donovan.

“China’s leaders have long been determined to suppress emerging religious movements they see as a threat to social order — a view they believe is validated by reports of religious fraud, counterfeit clerics, and cult-like pyramid schemes,” writes Donovan. Spiritual resurgence across China has alarmed Beijing, which sees non-state-sanctioned religious activities as a risk to national security.

Alongside the growth of non-official religious channels and a rise in religious content online, criminal networks that specialize in online scams have found new ways to defraud people looking for spiritual guidance on the internet. “In March 2024, China’s Ministry of Public Security announced that the police handled 77 major cases involving ‘spiritual cultivation’ training centers in the previous five years, confiscating assets worth over $30 million,” observes Donovan. In a bust of one of the religious scams, police arrested 46 people after more than 3,600 victims across 20 provinces reported losses totaling over $1.5 million.

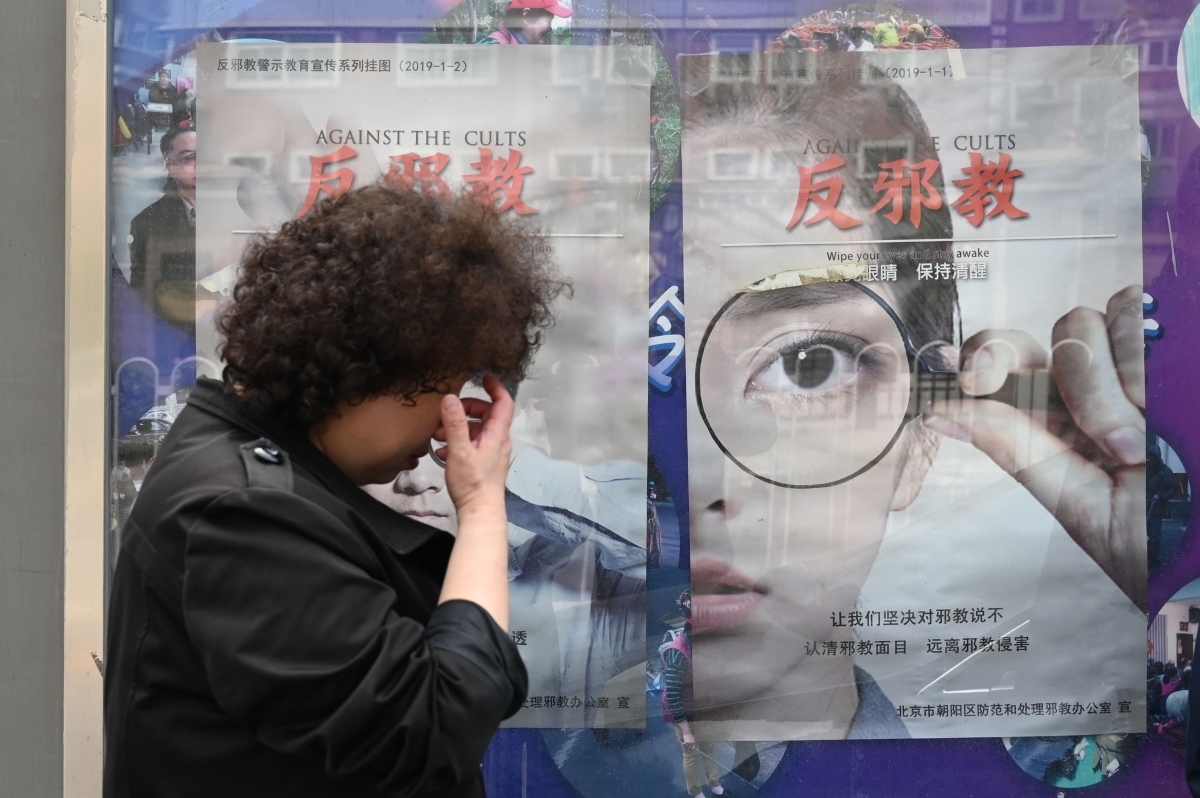

According to the report, China’s “Anti-Cult Network” — part of the effort to “draw a clear line around the religious activity that Beijing deems unacceptable” — was launched by the Ministry of Public Security in 2017, but Beijing’s anti-cult efforts go back much further. The term “xiejiao,” usually translated as “cult” or “evil religion,” is used to refer to any religious activity conducted outside the auspices of a state-sanctioned organization.

“The ongoing anti-cult campaign has its roots in the April 1999 Falun Gong sit-in outside the Zhongnanhai leadership compound in Beijing, an act of confrontation that made headlines around the world,” notes Donovan. “An anti-cult law enacted in October 1999 banned nineteen groups designated as cults; aside from the Falun Gong, this included fifteen unofficial Christian churches and three independent Buddhist sects.” In addition, local officials were given “wide discretion to crack down on all forms of independent religious expression.”

Despite Beijing’s efforts, “the stubborn persistence of religious scams and other types of fraud shows how much Beijing struggles to enforce standards of behavior, let alone control what people think,” concludes Donovan. Read the full report here.