magazine text block

In June 2009, protesters spilled into the streets of Tehran, demanding that Iranian President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad step down. The incumbent president had just won a second term, besting the reformist candidate Mir Hossein Mousavi with nearly twice as many votes. Those results drew outcry from opposition supporters who accused the government of fraud and said Ahmadinejad had stolen the election. As the months wore on, millions across the country took to the streets — the largest demonstration since Iran’s 1979 Islamic Revolution.

The Green Movement (named because protesters donned scarves and clothes in Mousavi’s campaign colors) ran until February 2010, when it was violently quashed, its leaders placed under house arrest and scores executed. Nearly a year before the Arab Spring sparked, Iran had started — and finished — its own populist movement.

In the United States, Iranian-American artist Shiva Ahmadi watched transfixed as the Middle East bloomed with hope, only to implode. Born and raised in Tehran, Ahmadi has long incorporated politics into her art. At a glance, her brightly colored paintings are delicate and beautiful — drawing on Persian artistic traditions. Look closer and the violence seeps through; war, bloodshed, and bombs traipse across the paper.

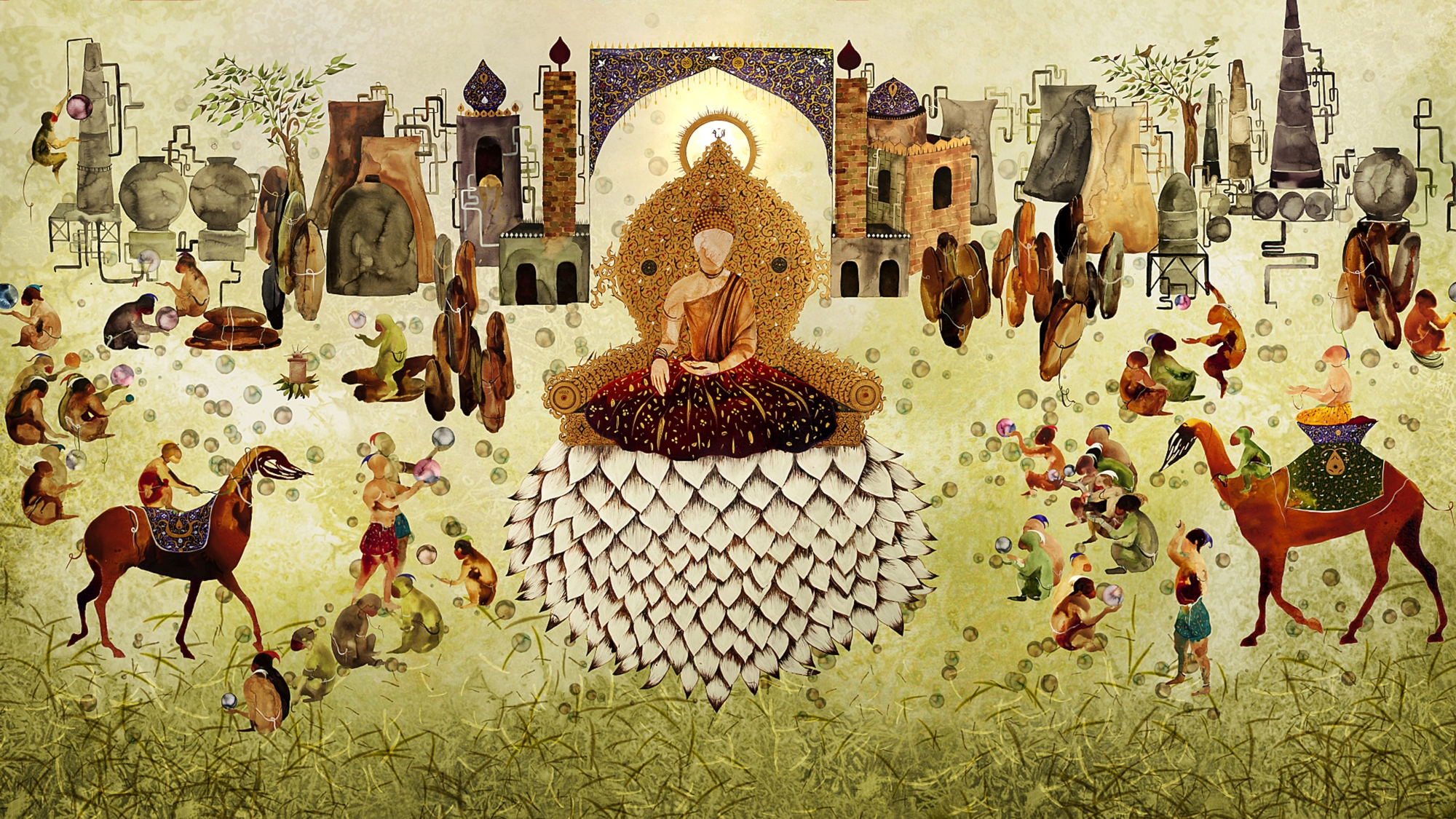

In 2014, Ahmadi exhibited “Lotus” at Asia Society Museum in New York. The work is a nine-minute animation of a watercolor and ink painting by the same name. In the original painting, a turbaned figure sits on a filligred throne — blood dripping from his face and body, a bomb gently resting on an outstretched hand. Monkeys and men clutching explosives are scattered across a landscape littered with arrows. In the background, smokestacks and oil refineries loom.

To create the animation, Ahmadi worked backwards. All starts bucolic: birds in the trees, a buddha on the throne, colored baubles in hand. This, says Ahmadi, is how life appears to be moving as well. “All these leaders who were promising hope and were supposed to save and protect people’s lives; they turned into tyrants and started turning on their own people.”

Here, Ahmadi speaks about how her work draws from the politics around her.

magazine text block

I started painting “Lotus” after the Iranian uprising, and was working on it when the Arab Spring began. Since I’m from the Middle East and grew up during the Iran-Iraq war, it’s always been important to me to pay attention to the larger world.

The animation of “Lotus” was based on a painting that I did a year earlier, in 2013. At that time I had no idea that I would be making an animation — it was far from my mind. I’d never done anything digital apart from a very small piece and I considered myself a painter.

My paintings are narrative and have many figures and animals scattered all over the place. When you look at it on a larger scale, you can see that all of these characters are spread around the surface doing their thing. Animating it actually made perfect sense because when the painting was finished and I was looking at it, I thought: What if I start bringing other elements to the work and move these characters around?

While I was working on “Lotus,” I began looking through the buddha statues in the Asia Society Museum collection. All these beautiful buddhas represent someone who is a leader with a serene character, someone who can bring everything and everyone together. They have such a big presence.

In the painting of “Lotus,” in the center, I had this leader or mullah who is sitting on a lotus flower. So I was looking at the buddha and looking back at the figure in the center of my painting — comparing their characters and who these people are. I thought: Wow, what if I just used the buddha to show what happened to all these other elements in the painting?

What happened? At the beginning of the “Lotus” animation, everything is so beautiful and playful and light, and then, once all these characters start moving, even the buddha cannot resist anymore and turns into a tyrant.

That’s exactly what was happening in the Middle East at the time. All these leaders who were promising hope and were supposed to save and protect people’s lives, they turned into tyrants and started turning on their own people.

When there is no democracy, when people basically don’t have any rights, when they don’t make the decisions, when one person controls everything — then corruption is always an inevitable part of it. It’s not a republic anymore. It’s going to be just a tyranny. That didn’t happen with the buddha because he was such a symbol of goodness and he was able to keep his image clean — but it really doesn’t happen in politics like that.

I moved to the United States 20 years ago and have gone back to Iran twice. I can’t comment about what is going on in Iran right now, but from what I see this is exactly what is happening. There is a small group in power that controls everybody’s lives.

I’m also an immigrant. I experienced 9/11, and the invasion of Iraq, and the Trump Muslim ban. Instability and anxiety has always been a big part of my life and I feel like it is a big part of many immigrants, especially from the Middle East.

It’s not easy to be an immigrant. It’s not easy to leave everything behind and move to another country with a new language, new culture, new everything. And it is definitely not easy to be profiled for political reasons.

For the longest time, the strategy in my work was that I want to make something where the surface is going to be very beautiful because the message is extremely ugly. I wanted to combine the two together so it would grab people’s attention but at the same time send the message.

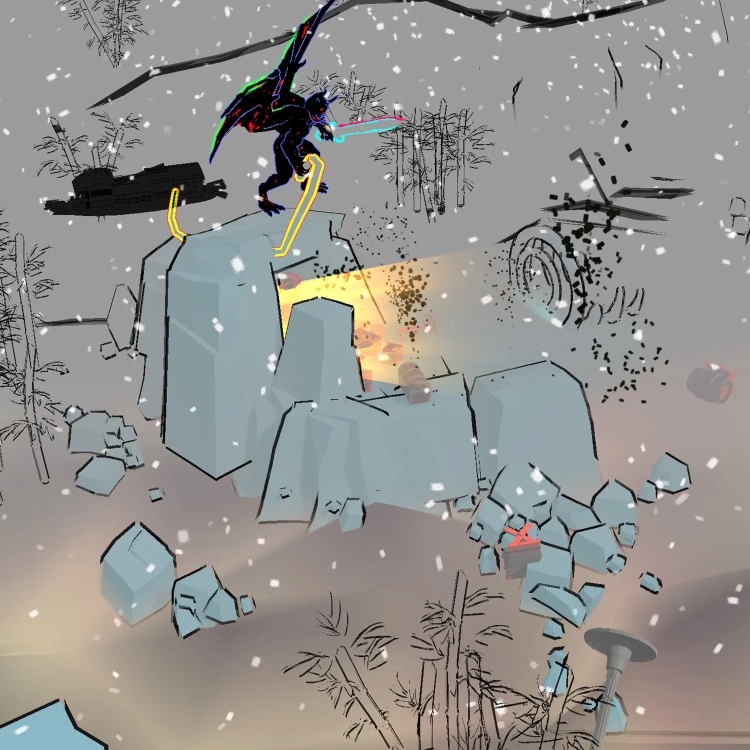

In the last few years, for me at least, it’s come to a point where things are extremely ugly on the surface and I can’t pretend anymore. The new animation I’m working on right now is about land theft and corruption. My work has become a little bit more transparent. It’s impossible to sugar coat what is happening.