magazine text block

Perhaps no individual better epitomizes the era of U.S.-China cultural exchange than Janet Yang. Born in New York City in 1956, the daughter of a longtime United Nations employee, Yang ignited a passion for her Chinese heritage as a teenager during a visit to Cultural Revolution-era China. During the 1980s, she worked to promote interest in Chinese cinema in the United States and, conversely, promoted American films in China — a period during which she worked with Steven Spielberg on his 1986 film Empire of the Sun. She then enjoyed a fruitful collaboration with another legendary director, Oliver Stone, and served as executive producer on the iconic adaptation of Amy Tan’s classic novel The Joy Luck Club. In the ensuing years, Yang has worked on numerous other films, including Dark Matter (starring Meryl Streep), The Weight of Water, and Shanghai Calling.

Throughout her career, Yang has proved that stories featuring Asia — and Asians — have widespread cultural viability, a fact that became self-evident with 2017’s global smash hit Crazy Rich Asians. But obstacles remain. A racist joke by comedian Chris Rock at that year’s Academy Awards reinforced the notion that Asians remained outsiders in Hollywood. In response, Yang helped rally a group of prominent Asian Americans in the entertainment industry in support of a letter-writing campaign and to call for meetings with the academy leadership, eventually leading to her own nomination as an Academy governor-at-large. By then, Yang had already co-founded the organization Gold House with Bing Chen, an entrepreneur and Asia 21 Young Leader, which works to promote Asian American representation in media, entertainment, and other industries. She also serves on the advisory board for Asia Society Southern California.

In this conversation with Asia Society Magazine, Yang reflects on her first impressions of China in the 1970s, her unlikely Hollywood journey, and the current state of U.S.-China cultural exchange. The conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Janet Yang, second from right, talks with director Steven Spielberg, center, on the set of his 1986 film 'Empire of the Sun,' filmed in Shanghai, China.

Courtesy of Janet Yang

magazine text block

Matt Schiavenza: You were born in Queens and grew up in Long Island in what you’ve described as a largely white community. How connected were you to your Chinese American identity back then? Did you have much consciousness about being Asian American?

Janet Yang: Growing up I had virtually no sense of an Asian American identity. I don’t even think that word ever came into my consciousness until probably the first time I visited China, which was in 1972.

What was it like then?

It was during the middle of the Cultural Revolution. [President Richard] Nixon and [National Security Adviser Henry] Kissinger had just come back from China and they encouraged Chinese American families, especially those who were Chinese citizens, as my mother was, to visit. It wasn’t until that visit that I was moved by my heritage and had a desire for a deeper understanding of it. I didn’t speak much Chinese then.

The very act of entering China was quite the ordeal. The country was considered a very frightening place at the time. Many of my parents’ friends didn’t want us to go — they thought it was too dangerous. But my mother, especially, was very determined to reunite with her family. My four grandparents had already died by then. Even still, my family members traveled separately, so that we’d have someone in the U.S. in case one of us somehow got stuck there.

We had a systematized list of what to bring to which relative: a certain amount of rice, a certain amount of flour, of sugar, of cloth. We got most of these items in Hong Kong, because the only way to get to China was to fly to Hong Kong, take a train to the border, walk across a rickety bridge, and then take another train from what is now Shenzhen.

The contrast between China and Hong Kong was jarring. There was an extremely strong military presence on the mainland, which I had never experienced, and I had never seen that level of poverty. When we went to our relatives’ home, we learned that they had slaughtered a chicken for us, which was a really big deal — they didn’t always have chicken. They had a stack of letters and photos we’d sent them but had been confiscated earlier in the Cultural Revolution and later returned to them. My cousin was studying English, and when I offered to help, I noticed that her textbook was very anti-American — it included messages like “down with the American paper tigers.”

And yet there was an intense curiosity and joy about them. Because my mother worked with the United Nations she was, at various times, accused of being a spy, and our relatives probably suffered because of that. Everyone seemed desperate to connect and at the same time scared out of their wits to say anything. We’d take walks and whisper to each other. I remember seeing my mother sobbing because she found out that her father, who was a supreme court judge in China and technically a landlord, was probably pushed out of a building — she had initially been told that it was suicide. There was a lot of drama in our family about who was and who wasn’t persecuted and why.

I looked like a taller, healthier version of my relatives. They were skinny and looked deprived. We were treated with incredible warmth and an almost inappropriate, undeserved adulation. And they were amazed with our toiletries. They’d never seen, say, a shower cap or contact lens case before — or really anything plastic.

You have to understand — the development of China into what it is today is miraculous.

On that trip, as we moved from hotel to hotel — there was usually only one hotel in each city allowed to accept foreigners — we’d keep the doors open because it was very hot. One night a Canadian Chinese man marched into my room and said, “You don’t realize it now, but being Chinese American is one day going to be very important to you. You are unaware of what that means — but you will have to come to grips with your identity.”

Like a prophecy!

Who was this person? How dare he say something like that to me?

But his words resonated with me, and even frightened me — I wasn’t sure how exactly it would all manifest itself. And it’s certainly true that that trip to China set me on a path from which I haven’t really diverged. After I came back, I decided that I wanted to study Chinese in college, and even that wasn’t enough: I wanted to live in China, especially because U.S.-China relations had by then been normalized. I found a job at the Foreign Language Press through a language teacher at Harvard. Suddenly, I had very specific notions about what I wanted to do with my life — at least in the short term.

Members of the cast of 'The Joy Luck Club,' for which Janet Yang served as executive producer, participate in a table read of the 1993 film’s script.

Courtesy of Janet Yang

Tamlyn Tomita, Tsai Chin, Janet Yang, Ming-na Wen, Kieu Chinh, Russell Wong, France Nuyen, Ronald Bass, Lauren Tom, Wayne Wang, and Amy Tan attend The Academy Presents 'The Joy Luck Club' (1993) 25th Anniversary at The Samuel Goldwyn Theater on August 22, 2018, in Beverly Hills, California.

Alberto E. Rodriguez/Getty Images

magazine text block

Eventually of course you built a career in film and television. How did that come about?

That initial 1972 trip gave me the spark to learn more about China, from reading Fox Butterfield articles in The New York Times to studying classical Chinese literature. But the year and a half I spent in China, in 1980-1981, was when I connected this passion into a professional life. I couldn’t get enough of Chinese films and television shows. It had never occurred to me in a million years that people who looked like me could do this. I had never seen a single example on screen, except for Bruce Lee or maybe Li Ning at the Olympics. I happened to make friends with a writer who introduced me to Wang Meng and others. I was so excited to talk to them because I had never had a creative conversation with anyone who was Asian. I met a filmmaker named Peng Ning, who had made a film called Sun and Man, starring Leng Mei, that I was so enamored with.

I wanted to know more. I thought — if the experience of seeing Asians on screen was so thrilling for me, maybe it would be thrilling to other people, too. I left China with the notion that I wanted to do something in film, because I knew it was going to change the perception of Asians.

Around that time, my family and I had helped a young Chinese writer obtain a scholarship at UCLA through Perry Link. We became friends, and one day he told me that he wanted to make a movie, a documentary where he’d travel across the United States. His English was very poor, so we had to find someone who was bilingual to accompany him. At first we approached Joan Chen, but she wasn’t available. So we hired an NYU film student named Ann Yen. We cobbled together a crew — our sound man was Ang Lee — and made the documentary. It’s called From East to West: America Through the Eyes of a Chinese.

Film was calling me. I started organizing Chinese film festivals, and through that I met a lot of cool people, including my future work partner, Oliver Stone. I would go to the Chinese consulate on 42nd Street and 12th Avenue and carry these really heavy 35-millimeter prints. And that’s when I discovered that there was a company in San Francisco that wanted to be the distributor of these films. I had just graduated from business school at Columbia. Everyone else was going to work for McKinsey and Goldman Sachs, and I was working for this little San Francisco company.

You went to China with Steven Spielberg for his film Empire of the Sun. What was that like?

I was busy promoting Chinese films within the art market and art museums, and taking Chinese delegations to film festivals, when someone from Universal Studios read about me in a San Francisco paper. And suddenly I had a job at Universal Studios. That was a big jump. By this point, I was pretty familiar with the film industry. I was then able to take American movies to China, including a retrospective I put together on Gregory Peck. What I found was that Chinese people were fascinated with American movies, even though they hadn’t, officially anyway, had access to American studio movies in decades. I can’t even describe the thrill it was for them to have that again.

It was from working at Universal that I heard that Steven was interested in making a movie in China. One thing led to another and I met with his producer, Kathleen Kennedy. I spent months in China being the liaison, the trainer, because nobody else had ever really spent time there. We shot these very, very large scenes in Shanghai where we essentially had to shut down the city. We had thousands of extras to manage, this giant team of people in a city that, while it wasn’t what it was in the ’70s, was certainly not what it is today. We were staying what was probably a three-and-a-half or four-star hotel. The only form of entertainment the hotel had was a bowling alley downstairs, and we ended up buying sidecars and raced through the hallways. We would go out in the street and gorge ourselves on dumplings and whatever.

But things were looking up. Bernardo Bertolucci was making The Last Emperor in Beijing, and there was so much excitement about China. It was a beautiful period because there was still so much innocence and curiosity. Film is a universal language. We were able to get a lot across, and there was a lot of mutual respect.

Janet Yang, right, and Abby Mann, executive producers of the 1996 HBO film 'Indictment: The McMartin Trial,' celebrate its Golden Globe for Best Miniseries or Television Film.

Courtesy of Janet Yang

magazine text block

I want to talk about The Joy Luck Club. You’ve spoken about how the idea was difficult to sell in 1993, because there wasn’t really a market for Asian American cinema. What do you think would have been different if you tried to make this film today?

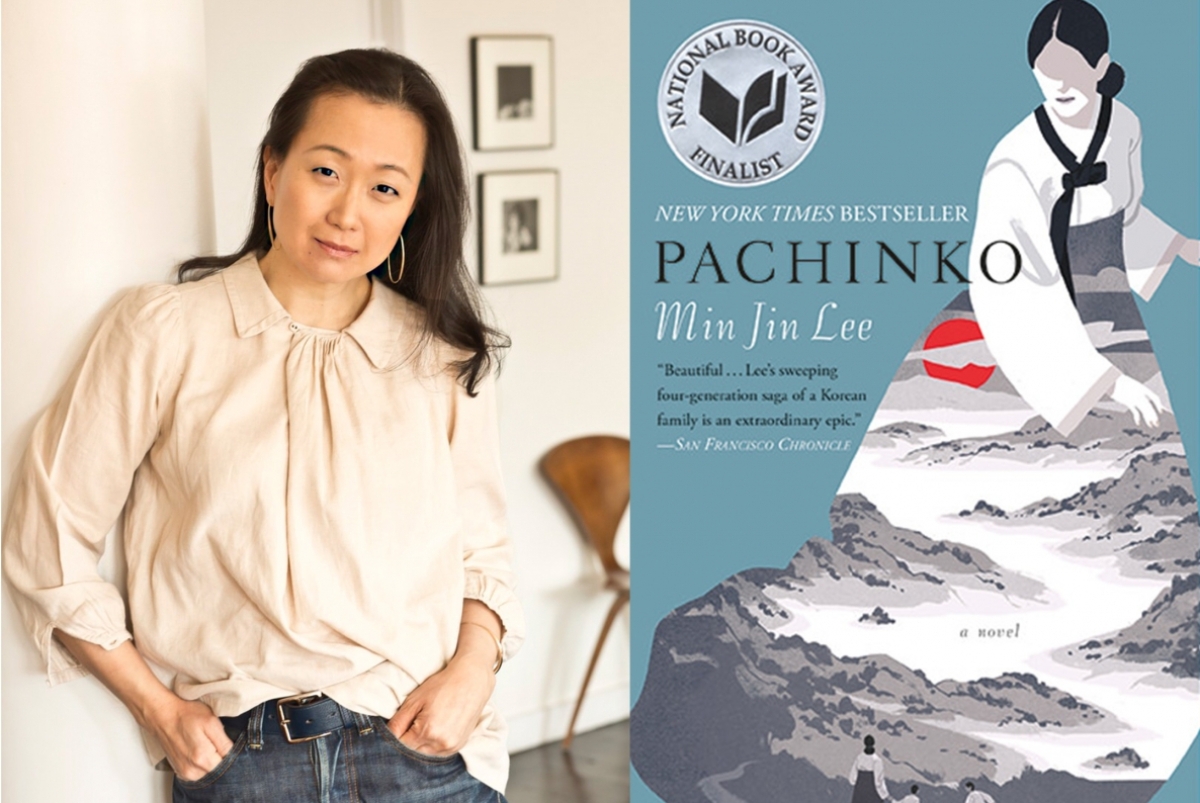

It would have been completely different. It wouldn’t be a studio film. Studios want to make very big budget films that can be franchises. The closest thing in tone to The Joy Luck Club that’s come out recently, I think, is Pachinko — which I love, but it’s a TV series. It’s possible The Joy Luck Club would have been a limited series, perhaps, or an indie film made by one of the streamers.

Fortunately, we were not pressured to hire stars at the time. Today, there are so many “name” Asian actors that we could have gotten someone famous, but it was never going to be a cast-driven movie. We probably wouldn’t have gotten that much money, either. It’s just very, very rare for studios to take chances nowadays on films without any overt commercial appeal. I revel in the fact that Pachinko has three languages going. Probably a quarter to a third of our film was subtitled, and that was a big breakthrough. It just broke so many rules. Even though it came from a bestselling novel, its success was still shocking.

So many Asian American filmmakers today acknowledge how The Joy Luck Club gave them the possibility to dream about one day doing that. That makes me feel so gratified. And not to mention all the people who tell me that the movie helped their relationship with their mother or father.

What kind of resistance did you encounter while pitching the movie?

It got rejected by 99% of the people in town! People said, “Oh, could you put some more white people in there?” It just seemed so preposterous to propose a movie like it at the time. If I’d known better, I probably wouldn’t have had the courage to do it. I was naïve and new to the business.

There was a long period where China and the rest of the world seemed to be converging in many ways, a period of engagement. And that’s obviously changed a lot in the last 10 years.

Ten years ago, things were wonderful. I’d say it’s really only been in the last three or four years, starting with Fan Bingbing’s arrest.

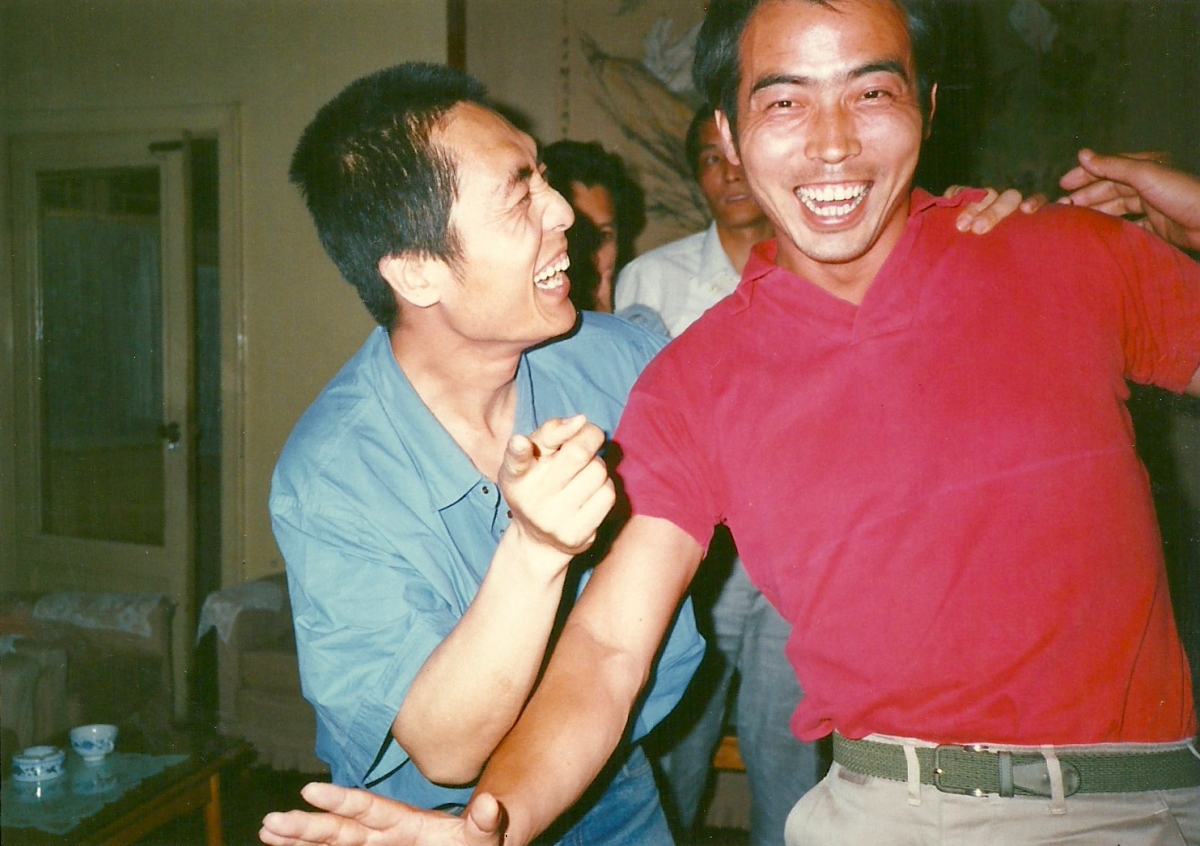

Celebrated Chinese film directors Zhang Yimou, left, and Chen Kaige share a laugh in Beijing in the 1980s.

Courtesy of Janet Yang

magazine text block

What kind of impact has this had on cultural exchange?

Are you kidding? It’s dead. I can’t say completely dead — but so many things have changed. For Asia Society, I chaired the U.S.-Asia Entertainment Summit. It had been the U.S.-Asia Film Summit, and it was once thriving as the U.S.-China Film Summit. We were able to bring over all the top Chinese directors and moguls for meetings with Hollywood moguls. Deals were being done, or at the very least a lot of flirtation and courtship and back and forth about projects. But at a certain point I said that we could no longer call it the U.S.-China Film Summit, because I didn’t think there was enough going on. We kept having to change the name and broaden the umbrella to make it viable. If I tried to do a U.S.-China Film Summit today, I don’t think anybody would show up.

Are there any reasons for hope?

I’m a hopeful and optimistic person. And things are always changing. But I think the waves of change aren’t coming from the current regimes. I currently don’t see many signs of change, but I know from studying history that it happens. It’s possible that things may have to get worse before they get better.