Domestic Politics

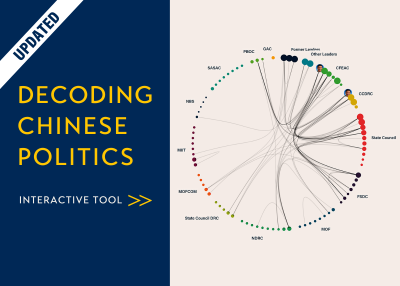

The Domestic Politics pillar of the Center for China Analysis (CCA) closely tracks developments within the Chinese Party-State (both the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) and the other branches of Chinese political system). Leveraging Chinese-language source materials and the Asia Society Policy Institute’s extensive network throughout China and the Asia-Pacific, we follow key personnel changes within the CCP leadership. We analyze their impact on China’s domestic and foreign policy decision-making processes and the effectiveness of the party’s implementation processes. We also pay close attention to center-local dynamics and regional distinctions in policy execution.

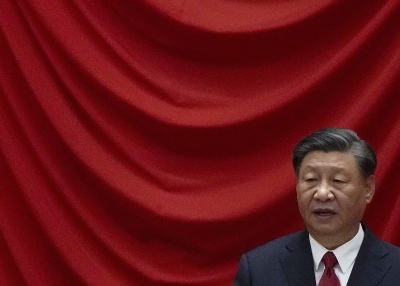

Importantly, this pillar also parses unfolding ideological trends within the CCP and explains their political, policy, and practical consequences, providing intensive analysis of Xi Jinping, his worldview, and his level of continuing control over the Chinese leadership’s decision-making process. Marxist-Leninist ideology still matters in China as it provides insight into longer-term policy change. Similarly, the role of nationalism within Xi’s new ideology of Marxist Nationalism represents a growing dynamic in Chinese politics. Therefore, a key role of this pillar — and the CCA as a whole — is to analyze ideological change.

Closely monitoring primary sources, the Domestic Politics pillar focuses on personnel changes within the Politburo, the Central Committee, and the State Council. This is also a reliable indicator through which to evaluate policy change. While Xi is critical to every area of governance, he does not personally make and execute every decision within the central leadership. As a result, it is vital that we understand the political backgrounds, motivations, and ideologies of the officials within central governing bodies — and the degree to which each of them aligns with Xi’s.

Another crucial facet of personnel makeup is centered on generational change. Xi and others from his generation spent their formative years in the midst of China’s Cultural Revolution; they were groomed for their roles and in a sense represent “red royalty.” But we must understand the political profiles of the next generation of leaders as well, who came to political maturity during the period of reform and opening. Then there is the rising generation who have come to adulthood under Xi’s new Marxist Nationalism, where the “lure of the West” is less strong. Tracking these changing generational sentiments is also important to make sense of emerging fault lines in Chinese domestic politics, which in turn influence the sociopolitical developments which fall under each of the CCA’s four other pillars.