Filmmaker Chris Hilton on the Anti-Communist Purges in Indonesia in 1965-66

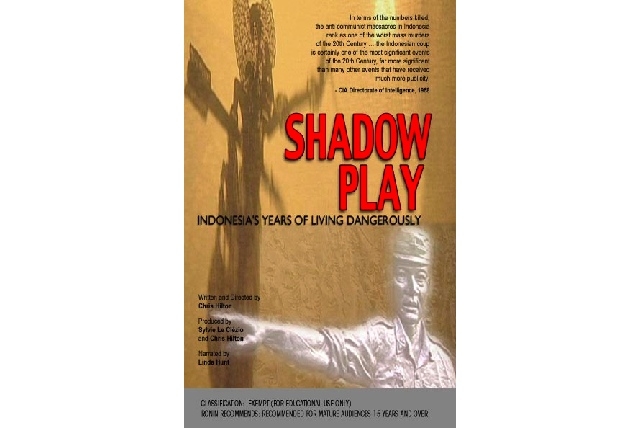

A new documentary, Shadow Play, by the Australian award-winning filmmaker, Chris Hilton, deals with the anti-communist purges in Indonesia in 1965-66, during which up to a million Indonesians are estimated to have been killed. Using recently declassified documents, Shadow Play also reveals the extent to which Western powers may have been involved in the events leading up to the overthrow of President Sukarno in Indonesia in 1966, and in what the CIA itself has termed "one of the worst mass murders of the 20th century."

Here Chris Hilton explains why he became interested in the subject, what areas the documentary covers, and what its likely reception will be here in the United States.

Your documentary, Shadow Play, discusses American, British and Australian complicity in the mass murder of communists and alleged communists in Indonesia in 1965-66. When were the official documents exposing this complicity revealed to the public, and under what conditions? That is, what prompted the US government to reveal these when they did? In any case, prior to their revelation, there must have been some speculation about American involvement in the massacre.

Yes, there was quite a bit of speculation even before the documents were released. About 20 or 30 years after an event, the State Department writes an official history of what happened. The State Department released these documents having to do with US involvement in Indonesia through normal declassification procedures. In fact a draft had been written of the official history of the State Department in Indonesia and Malaysia in 1964-66. There was a volume that was prepared by an official historian in the State Department; this volume was then reviewed by the CIA and withdrawn from publication because they had some concerns about it but it was accidentally published and posted on a website. So it was because of this lapse in the declassification process that the most overt connections between the US government and the Indonesian military during that time were revealed. This is the story of the United States.

As far as Britain is concerned, a lot of the information is available in the Foreign Office archives. It is quite clear that the British wanted a change of government in Indonesia but the physical proof of their various manipulations is not as obvious. The cables often talk about how the British government should be involved in propaganda, in influencing people's opinions in Indonesia as much as possible, but in terms of covert operations, there still is nothing on the record, nothing written explicitly saying that Sukarno ought to be assassinated or anything like that, even though we strongly suspect that this was also happening.

In terms of the film, one of the significant elements came from the head of the propaganda operation who actually revealed information which we were able to get hold of before he died to other journalists. His name was Norman Reddaway; he appears in one version of the documentary although not the one that is being aired on PBS. Norman Reddaway was an official propagandist from the British Foreign Office and had worked in World War II and had also been involved in different British campaigns like the Suez Crisis and was sent out to Singapore to take charge of this operation.

He appears in the 79-minute version, which is the longer one, and is also more in-depth. We do a lot more in that film on the press and information manipulation and propaganda.

How did you become interested in this event?

I grew up in Indonesia as an adolescent, in Central Java, because my parents were working there, so I got to hear lots of stories. I also remember being told by my parents, at the age of 13, not to discuss politics around the table or anywhere in the country, which struck me as rather unusual. This made me even more intrigued by what it was that had transpired in Central Java seven years before I was there. I had met missionaries and other people who had been there then and had very dark stories to tell.

Of course when Suharto's regime fell [in 1998], it became possible to revisit the whole issue of what happened.

In your documentary, you say that Indonesia's military under Suharto murdered more of its own population than any other regime supported by the West and that the military operated very much as a political party. How is it that one can account for the power of the institution?

It has mostly to do with the revolution; the history of Indonesia was essentially as a fragmented country of multiple nations, multiple languages. It became the Dutch East Indies under the Dutch and only became the nation of Indonesia through a war of independence which was fought by initially a rag-tag groups of guerilla fighters who linked themselves up informally. These groups then became the Indonesian army. So effectively it was the most powerful institution in the country from day one.

You say in the documentary that after the 1957 elections, in which the Communist Party of Indonesia (PKI) fared well, the US started supporting insurgencies throughout Indonesia. What effects did this American involvement have on the shape these insurgencies subsequently took? Were these insurgencies actually expressions of popular discontent, either against Sukarno or the centralized nature of the Indonesian state? Or were they actually created or propelled by the support they received from the outside? What was the effect of this involvement on US-Indonesian relations?

You will hear the argument mounted both ways. If one is interested in a regime change, one cultivates opposition elements. Now to what extent those elements could achieve their ends on their own is possibly the major question. In this case, there is no doubt that there was a major US military intervention. More guns, bombs, planes, and bombing raids were run in that operation than any other operation even against Mao and in support of the KMT in the 1950s; so it was a major operation.

The Americans flew bombing missions themselves. American pilots from the US Air Force operating under CIA command from the Philippines ran bombing raids against the Indonesian military. An American pilot named Allen Pope was shot down in 1957. He was shot down while bombing a church and a port in Ambon. His plane was hit, he parachuted out, and was arrested and put on trial in Indonesia. The most significant thing is that he was shot down with his papers on him. Normally when officers fly in this kind of covert mission, they carry no identification with them; in the event that they are caught, they say they were acting as a mercenary. He actually had a copy of his orders with him. The Indonesians got hold of the orders, he was put on trial, given the death penalty but treated very well, in the sense that he was kept under a house-arrest situation. His release was secured by Robert Kennedy in 1962 through intensive diplomacy.

So it is absolutely clear, through other studies that have been done as well of Eisenhower's and Dulles' records, that there was a huge covert operation in Indonesia, supporting the insurgencies with bombs, guns, ships, planes, etc. There were two places in particular where these insurgencies were: a region in Sumatra and the other was in the very northern tip of Sulawesi.

American involvement clearly strengthened these insurgencies materially. The insurgencies seemed to be run by a bunch of disaffected colonels who wanted to run the country themselves. The effect was that the Indonesian army put these rebellions down rather effectively within 18 months or so.

US support for these insurgencies was viewed by Indonesia as an act of betrayal by the West (the British and the Australians were also involved in supporting this covert operation). So it shattered trust and isolated Sukarno and made him paranoid (although justly suspicious is probably more accurate) and pushed him more over to the Soviet camp. Even after this happened, the Indonesians went back to the Americans in 1958 asking for military supplies to put down other rebellions. When they were refused by the Americans, they got supplies from the Soviet Union.

You also say in the documentary that the New York Times applauded Suharto's takeover, saying it was a "gleam of light in Asia". This perhaps is to be expected from an establishment newspaper but was there any other opposing coverage in this country at the time?

I think all the coverage was more or less the same. All this happened in a place a long way away at a time when US troops were on the ground in Vietnam in numbers unprecedented since World War II, so there was obviously major concern about that. Nothing was known really about what happened in Indonesia and because the Indonesian army and the Australians, the British, and the Americans, had such control over the information that was made public, nothing was really known. Ultimately this anti-Communist operation was simply passed off in the West and elsewhere as a civil war. The information was controlled quite effectively; the true story did not get out at all.

It is quite striking that none of the American government officials interviewed in the documentary expressed much remorse about their involvement in what the CIA itself has termed "one of the worst mass murders of the 20th century". Is it the case that much of the American foreign policy establishment still believes that there were no other options given the fear of Indonesia coming under the influence of China (and the attendant "domino theory" consequences)?

Yes, pretty much. It is difficult to speculate but in Cambodia, Pol Pot took over with his mad Maoist ideas and killed 1.7 million people. There is no doubt that there was a very, very strong communist party in Indonesia that was coming under the influence more and more of China. This is the period when the Cultural Revolution was on and the temperature was rising in Indonesia. It had been through the previous 15 years of the Cold War and although Indonesia had tried to remain neutral, it had become polarized inside. There were anti-communists threatening the communists, and vice versa.

The tensions were high in Indonesia. The West was very keen for an anti-communist victory and wanted to do what they could to make sure it would happen. But did they premeditate the deaths of 500,000-1 million people? No. Could they have predicted the deaths? Probably.

So in a sense they can feel guilt-free because they can say that they could not have predicted a massacre on that scale.

The problem is that there is still a lot we do not know. Was the CIA involved or not, for instance? I grilled this head of station for four hours and I know these people are taught how to lie and so forth, so we had all sorts of tricky questions for him, but we weren't able to get him to admit to anything.

In any case, it is quite inconceivable to me that the whole murder of the generals was a plot conceived in Washington.

What responses do you expect in the US to this documentary being aired? You said earlier, and I wasn't aware of this, that there are two versions of the documentary: a 79-minute one which is being aired in Britain, Australia and Finland and a shorter one for the US. Why was there a shorter version for PBS?

Slot length had something to do with it. Most TV stations operate on a one-hour turnaround, so PBS wanted a shorter length. Maybe they felt that a massacre movie would not hold the interest of the viewers for 79 minutes; you have to be pretty dedicated to watch a forensic analysis of a massacre for that long.

So it is not as though you edited out certain bits that you thought might be too controversial in the American context.

I did remove some parts that would be less palatable for an American audience, such as the text of a couple of cables from the American Embassy in Jakarta, just more evidence that the American administration was really anxious that the Indonesian army should move against the communists and really finish them off. There is a CIA officer in the longer version who says something fairly cynical, something like, "It was just really great that all these communists were finished off with Soviet weapons and not American ones; there is a fantastic irony in that."

Comments like that -- which were damning, not at an argumentative level but at the level of tone and attitude -- were edited out.

And what kind of reaction do you expect from your viewers in the United States?

I don't really expect it to be wildly controversial because we're just quoting what has been on the public record. The most controversial parts are about giving money to militia groups who then went on to kill the communists but that was already out last year. It was run in the Washington Post and a couple of other papers. This had been stringently denied for so long.

When this cable was finally declassified it was finally proven. Even the State Department history said this but there was a great deal of controversy when this assertion had been previously made in the press in the absence of hard evidence.

It will probably be enlightening for American people to see how their foreign policy affected other nations in a broad context, and to reflect on their own position in the world. But in terms of headline-grabbing revelations, we could only go on what had already been declassified. We were not able to find a smoking gun; we weren't able to get the CIA guy to admit to anything and yet we know that there are hundreds of pages that are blacked out still. When they requested money in Jakarta to give to the death squads, the four-page reply came from William Colby of the CIA, which hasn't got one word declassified, so the CIA could have been giving very detailed instructions about how to arm and train death squads, but we do not know, and may never know.

For more information about the documentary, please visit the Shadow Play website on PBS.

Interview conducted by Nermeen Shaikh of Asia Society.