The Face of Thailand's Hybrid Authoritarianism

By Thitinan Pongsudhrak

Although she has been granted bail, the second arrest of Prachatai Online webmaster Chiranuch Premchaiporn last Friday exposes Thailand's solidifying "soft" civil-military authoritarianism. Such authoritarianism is "soft" because it is tailored for the globalization age where domestic legitimacy and international credibility matter more than in past eras of outright military-authoritarian rule. This decidedly nuanced and disguised authoritarianism thus revolves around a necessary hybrid of a civilian democratic façade with a military spine.

Chiranuch's case is merely symptomatic of this hybrid authoritarianism. Her first arrest transpired in early 2009 for charges of allowing offensive comments on Prachatai's web board in violation of Section 112 of the Criminal Code and the 2007 Computer Crimes Act. This time around, similar charges appear to have been filed by an individual, whose identity is unclear, in Khon Kaen province. Chiranuch was ironically booked at Bangkok's Suvarnabhumi Airport and taken by car to Khon Kaen after returning from a European international conference on Internet freedom.

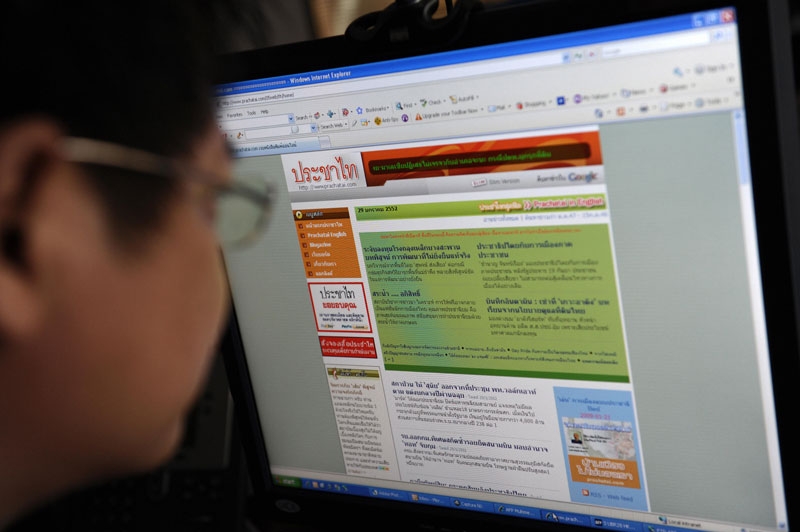

What her legal saga portends is growing censorship and selective persecution of those who are deemed to harbour the wrong thoughts. Freedom of expression in Thailand is an endangered commodity. To be sure, Prachatai is left-leaning in a country whose powers-that-be are shifting even more to the right. But Prachatai is no more to the left than its myriad counterparts in other countries that are receptive to dissenting opinions and open to fair comment and criticisms of the status quo and conventional wisdom.

Without offsetting news and opinion sources, Thailand would be skewed by the government's official news apparatus, reinforced by one-way rightist propaganda elsewhere. That Prachatai and its progressive cohorts, many now blocked by the ICT ministry, serve to balance out opposing views should be seen as healthy and warranted for Thai society. Otherwise the suppressed and stifled dissent will only accumulate and find manifestations in a pent-up fashion that can only be detrimental to national well-being.

While Chiranuch's ordeal is relatively high-profile, it epitomizes a plethora of other cases that have found little voice because of the climate of fear, intimidation, and coercion attendant with civil-military hybrid repression. These cases include the persecution of university students who have been gagged, harassed, and made to undergo psychological tests for their political beliefs. A professor at a well-known university has been detained at an army barracks for a week with neither charges nor apology on his release. A youthful aspiring entertainer was pressured to withdraw from a reality TV show because he had criticised Prime Minister Abhisit Vejjajiva. A high school graduate was denied a place at a leading university after passing the national admissions test because of political opinion.

Thailand's world of academe has never sunk so low under ostensible democratic rule. Lecturers in these parts typically resort to all manners of inducement to generate student views and opinions from basic encouragement and plea to veiled threats of points reduction on final grades. When the young speak, we should listen with encouragement and constructive reply. But in this period of soft repression, ironically presided over by a PM who was once a lecturer, the younger generation has been suppressed.

The list of the suppressed is not confined to the young. In rural Thailand, many dozens of individuals who act on officially unsanctioned thoughts are languishing in jail and army barracks. Some have quietly met expeditious jail terms for similar charges that hound Chiranuch. Many are on the run. The air of intimidation and fear is pervasive. And it works.

What is perhaps more dangerous than official censorship and suppression is self-censorship. The fear is such that penmanship is voluntarily curtailed and spoken words become more muted and subtle. Such an environment has led to a double asymmetry in media coverage of Thai politics.

The first centres on the yawning gap in the Thai media between what takes place and what is reported. Less reporting on cases of dissent is evident in the Thai media, and most evident in the mostly state-owned Thai electronic media. The Thai press has a wider coverage but it is biased in favour of leaving out controversies rather than including them. New media sources on the internet face one-way blockage from the ICT authorities. If online content is pro-officialdom, it stays. Otherwise it is blocked. Those in between must always tread a fine line that too often compromises their full expression.

The second gap is between the Thai and foreign media. As the Thai media keep their heads down, the foreign media stick out by comparison. This is why official dealings with foreign media have become increasingly contentious, leading to xenophobic fear-mongering and conspiracy allegations of a phantom plot from the outside world to undermine and subvert the Thai order.

Prime Minister Abhisit admitted in the recent past that certain laws and their enforcement should come under review and under reform. But nothing has happened, as with much of the PM's right-sounding words and mixed or empty results. Such duplicity relies on a serial doublespeak. Chiranuch's case will be a test on the PM's moral rectitude, the viability of Thailand's legal infrastructure and the solidity of hybrid authoritarian rule.

Thitinan Pongsudhrak is Director of the Institute of Security and International Studies, Faculty of Political Science, Chulalongkorn University and a former participant in Asia Society’s Asia 21 Young Leaders Summit.

Related Link:

Thailand 'Determined to Become Mature Democracy'

Speaking at Asia Society on September 28, 2010, Thai Foreign Minister Kasit Piromya rejects assertions that Thailand's government is curtailing freedom of expression.