Anatomy of an Introductory Language Lesson

By Chris Livaccari

As a teacher of world languages, I have often found it helpful to study examples from languages that are unfamiliar to me. Many times, the more strange and different a language is from ones with which I am familiar, the more I learn about the actual art and craft of language teaching and learning. This is why, for our reading audience of primarily Chinese language educators, I've decided to present here a short introductory Japanese lesson.

As many teachers prepare to get back to school and start the new academic year, I thought it may also be useful to offer simple examples of ways in which to consider opening your first language class, particularly if your students are new to the language. The video clips included here were recorded with students at the College of Staten Island High School for International Studies (CSI High School), where I taught from 2005-2008.

I try to open the first class with a lot of enthusiasm. I spend most of this first class using only the target language, and I try to spend about the last quarter of the period coming back into English. I ask students to reflect on their experiences of learning in the target language, and set up expectations going forward.*

My goal on day one of class is to get the students excited about learning the language, expose them to the language in as natural a context as possible (with lots of connected speech and sentences that they will not understand), and make them feel that the classroom is a safe place to try new things, make mistakes, and explore.

Say Hello!

I use the first 30 seconds of class here to bring the students’ energy level up and give them a bit of a surprise. We practice the basic Japanese greeting individually and as a group, incorporating a bit of rhythm and chanting.

How Are You?

Here I try to use some facial expressions and gestures to convey the basic meanings of “how are you?” and the responses “fine,” “not well,” and “so-so.” I tried to repeat enough times that students get the language in their heads, but not too many times that they get bored. It’s really important in this first interaction with students to make sure that they feel comfortable and supported and understand that they should feel free to try out new language, even if they can’t get it perfectly.

Names

Here I introduce the students to the phrase “my name is…” and bring back the earlier expressions to get them ready to do some basic self-introductions. I try to keep the humor and energy going so that the students walk into this class feeling that they’ve entered a very unique environment, and one in which learning, exploration, and having fun come together.

Nationality

For the purposes of this particular lesson, I only introduce the terms for “American” and “Japanese,” just in order to give students the most basic tools for talking about themselves and getting ready to interact with Japanese people. I try to also emphasize the words for “yes” (hai) and “no” (iie), and the verb “to be” (desu). At the end of class, I would have the students analyze this a bit in English and understand that the verb “to be” comes at the end of the sentence in Japanese and that it does not change for gender, person, or number, as in many European languages. I also slip in the expression “so-o,” meaning “that’s right.”

Putting the Basics Together

Teacher with Students

After about six minutes of practice, the students are now ready to do a basic self- introduction, in this first iteration together with the teacher. In this first class, you will often get a good idea of which students have an “ear” for language and which will have a harder time getting the sounds and structures correctly, and it’s important to start making those mental notes, but it’s also important to support students in what can be a very frustrating and embarrassing experience for students, who are putting themselves out there and showing their potential vulnerabilities.

Putting the Basics Together

Students with Each Other

After some more practice with the teacher and the introduction of the word “goodbye” (sayonara), it’s time for the students to practice in pairs. So after about 8-10 minutes of practice, the students are ready to do a very basic self-introduction and have started to process the language and get a feel for its sounds and structures.

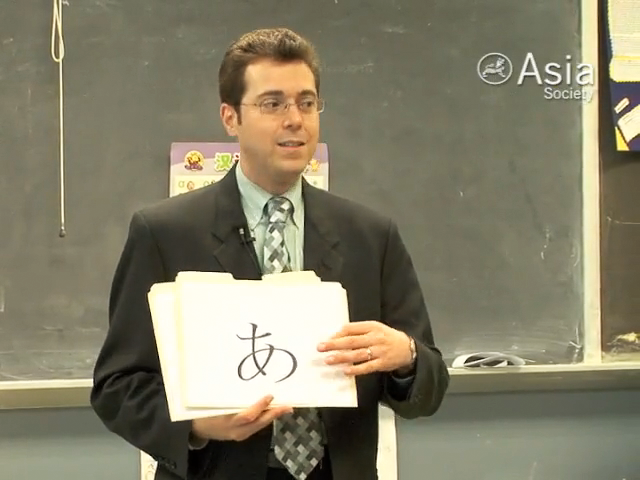

Basic Reading and Writing

After learning to introduce themselves, I get the students familiar with basic Japanese writing, in this case the hiragana syllabary. I use flashcards that flip open with the English letters that represent their meaning (I do the same thing with Chinese characters and pinyin). After they learn the first five letters, I introduce some words that they can read using them. Since the letters “a” and “o” look quite similar, at some point I need to hold up these two cards together and let the students compare.

Break for Analysis

After about 15 minutes, the students are familiar with the sounds and most basic structures of Japanese, greetings and self-introductions, the first five letters of the writing system and the ways in which words are made with them.

Again, in all of these activities I try to walk the balance between repetition and keeping things fresh. Sometimes I get it right, and sometimes I repeat myself too much or move forward too quickly, but you adjust and learn by embracing the dynamism of the classroom. It really can be a dance and an art, and something thrilling for both teachers and students.

At this point, depending on the length of the class period, I would want to bring the rhythm of the class down a bit and have students look at some Japanese writing, including those first five letters, the full hiragana chart, and some of the basic expressions we practiced orally. If it were a 50–60 minute period, I would spend about another 15–20 minutes with written tasks and then come into English to do some basic reflections on what the students had experienced, e.g.:

- What did it feel like to hear and see nothing but Japanese for 30 minutes?

- What did you notice about the Japanese language? How does it sound?

- How is Japanese different from English? Grammar [word order is reversed]? Writing [letters are syllables rather than single phonemes]?

- What do you want to know more about?

In terms of pacing and rhythm, I generally think there needs to be a flow, so when I taught 90-minute periods I would often think of them as 20-minute segments and try to have a mix of high-energy and low-energy moments, generally starting and ending the class with high energy and slowing things down a bit in the middle.

Introducing Numbers with Humor

At the end of the class, I want the students to leave with another burst of energy and some more new language, so I introduce numbers in a humorous and dynamic way by making (silly) connections between Japanese sounds and English words.

One = ichi = “itchy”

Two = ni = “knee”

Three = san = “sun”

Four = shi = “she”

Five = go = “to go”

Six = roku = “rock music”

Seven = nana = “nana/grandma”

Eight = hatchi = “hachoo/sneeze”

Nine = kyu = “pool cue”

Ten (jyu) does not sound like any appropriate English word, so I just leave it as an exception. I once taught at a school with many Jewish students, and several of them suggested using “Jew” for ten (jyu) and drawing a star of David in the air, but this never seemed appropriate or respectful enough to me.

I make a mistake here, because there are two words for “four” and “seven” and I initially don’t use the word for “seven” that goes with the English sounds. I leave this mistake in to show that teachers can make mistakes too, and students are less likely to be bothered by this if you create an environment in which trying your best and correcting yourself are values, and everyone feels engaged in the learning process. It never hurts to show your students that you learn as much as they do every day, both through their insights and experiences and through revisiting your own understanding of the course content and teaching methodology.

We’ll use all of this language more during the rest of the first week’s class, as well, and spend about half of one class discussing--and dissecting--students’ images (and misperceptions) of Japan and Japanese culture.

Special thanks to CSI High School for their participation in this demonstration. CSI High School is a member of the Asia Society International Studies Schools Network (ISSN) and opened in 2005 on the campus of the College of Staten Island. The school moved to a new building in 2009, and I returned to the school in 2010 to record these videos.

* There is a lot of debate about when and how to use the native and target language in class, and I would say that this really depends on the environment in which you are teaching. When I started at CSI High School, it was in its first year and we only had seven teachers and just over 100 students. As a teacher in such a small school, I had many roles to fill with students beyond that of a language teacher, so I used mostly the target language in class, but interacted a lot in English with students in other contexts. I also tried to use English to provide context and have the students think critically and analytically about their growing proficiency in the language—to talk about grammatical structures, the origins of Chinese characters, or the position of the mouth and tongue when making sounds that are difficult to pronounce.