For Yoshitomo Nara, Defining Art by Ethnicity is an 'Outdated Methodology'

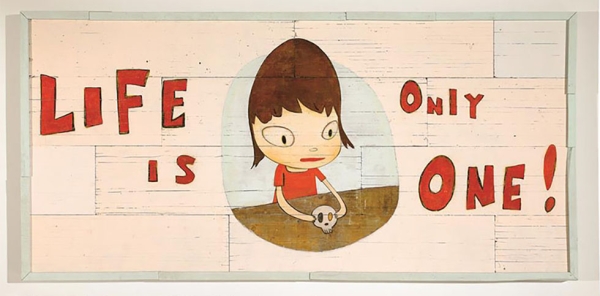

Life is Only One: Yoshitomo Nara, the first major Hong Kong exhibition for Japanese contemporary artist Yoshitomo Nara, is on view at Asia Society Hong Kong from March 6 to July 26, 2015. Learn more

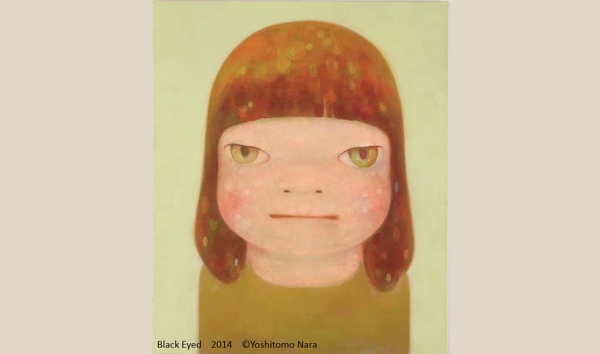

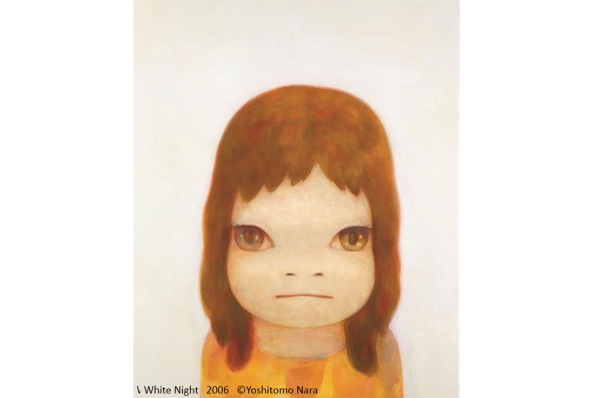

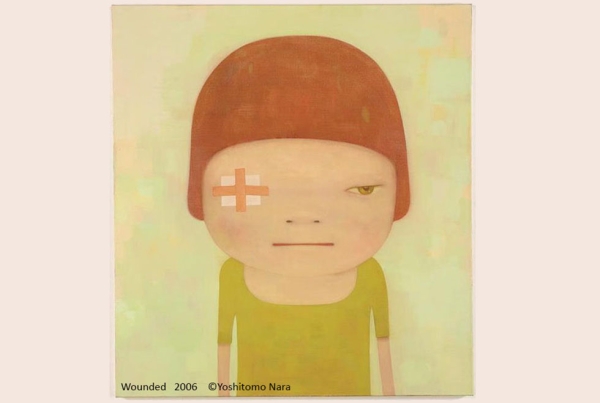

Yoshitomo Nara (b. 1959 in Hirosaki, Japan) is an internationally renown contemporary artist. He is known for depicting small children and animals in solitary settings, and works in multiple art forms, including painting, drawing, sculpture, and large-scale installations.

This month marks the opening of Nara’s first major solo exhibition in Hong Kong, Life is Only One: Yoshitomo Nara, presented by the Hong Kong Jockey Club at Asia Society. Featuring a collection drawn from the past two decades, the exhibition is an evocative journey into Nara’s open-ended interpretation of life, and aims to introduce his work to the local audience in Hong Kong from the artist’s personal perspective. It comes after Yoshimoto Nara: Nobody’s Fool, the artist’s 2010 solo debut in New York at Asia Society Museum.

Leading up to Life is Only One, Nara spoke with guest curator Fumio Nanjo, Director of the Mori Art Museum in Tokyo, and in-house curator Dominique Chan, Head of Gallery and Exhibition at Asia Society Hong Kong Center. Read an excerpt from the Q&A below for an insightful backdrop to the exhibition.

Chan: Nara-san, this exhibition is titled Life is Only One. Perhaps we can start by asking: What can you tell us about your life at this point in time?

Nara: When I was a child, the word “life” itself, of course, was a foreign concept. After turning 50, however, and with the deaths of people close to me and with the recent earthquake, I started to think about life more realistically — the limits of life, and the importance of what one can accomplish during that time.

Nanjo: Many of your paintings are of children. Can you say a little about how you developed this theme, and how you relate to those children you are painting? For you, who are they?

Nara: When I first started studying art, I was capturing what was in front of my eyes, and found pleasure in the moment when the paint was suddenly transformed into a phenomenon that had a reality (almost like a photograph). The children were not something I had sought or thought out, but in trying to capture what was in front of my eyes, they appeared as I tried to capture what was formless in my mind. I think, therefore, that my world expands upon my past experiences and memories, and the speaker for my own mind appears as a child. But really, if anything, those children appeared very naturally on the picture plane.

Chan: In this exhibition, there are photographs taken during your recent trip to the Sakhalin Island. What was the purpose of the trip?

Nara: The trip was a little personal — my maternal grandfather who was a farmer went to work as a coal miner in South Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands, which are former Japanese territories, during the agricultural off-season period. I wanted to see the landscapes that my grandfather had also seen. And as a Japanese person who was born and raised in the northern part of the country, I had the tendency to want to travel to the south; now I want to see the north where my roots are. Also, I have a kind of respect towards the ethnic minorities of the north, and feel connected to them as a northerner.

Nanjo: Many contemporary Asian artists are often defined by their nationality — Cai Guoqiang is often described as a Chinese artist, although a lot of his early support came from his time living in Japan; Murakami is often defined by his Japanese identity despite his international reputation; while many Euro-American artists are rarely defined by where they come from. Do you see yourself being defined by your national/ethnic identity?

Nara: I grew up listening to and loving the 60s to 70s music from the U.S. and England, and so my “geek-level” of knowledge is more than that of an average American or British person of my generation. This is one of the consequences of postwar Japan when American culture flooded the country. I think becoming more knowledgeable about something other than the culture where one is from epitomizes a global culture that transcends boundaries between countries and ethnicities. And I think defining artwork according to nationalities and ethnicities is a rather outdated methodology. Also, even for conceptual art, although there was a tendency to label something as “German” or “Eastern European” or “French” before, now with more accessible information sharing owing to the Internet, I feel that even those tendencies are now being disregarded.

Chan: The 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake was a tragedy that affected everyone who lived in or has a connection with Japan. Many artists have responded to the event in different ways. What impact did the event have on you in terms of creativity?

Nara: In my case, I could no longer see art as something positive. Art is something that is borne out of luxury, and it is because of that luxury that man’s imagination can begin to create. After the earthquake, I made sculptural works using a primitive method of clay modeling without the use of sculpting tools, but with just my two hands. It felt like a return to the fundamental act of making, but I also wonder if it was my defense mechanism as an artist kicking in.

Chan: Last question: What do you want the audience to get from seeing this exhibition?

Nara: I don’t have anything particular in mind. As always, the reaction of the audience can make one feel a little happy or a little sad. I never wish to have people understand me, nor do I want to force my views on people. But, like with an audience at a music concert, I hope that the attending my exhibition with others will create a sense shared experience.