Welcome Back to the Industrial Revolution

The latest turmoil in global stock markets following Standard & Poor’s decision to downgrade its rating of the United States government has led many to fear another serious economic downturn. We asked our Sustainability Roundtable what hopes might exist for global cooperation on sustainability issues like food security, energy policy, and climate change in a renewed economic crisis? Is it possible for any of these issues to play an important part of international policy discussions?

Adam Moser is the China Environment Fellow at Vermont Law School's US-China Partnership for Environmental Law and he blogs at China Environmental Governance.

If economic growth, in GDP terms, is a prerequisite for addressing environmental sustainability issues, is there any hope for achieving real sustainability?

Back in 2009, countries around the world pumped more than $500 billion in green stimulus spending into their economies — nearly 16 percent of all global stimulus spending. But now, Western countries are burdened with debt and have no budget for — and even less political will — to delve into major stimulus spending again. A Green Marshall Plan is not very likely.

Many Asian countries are faring better in this regard. China is still riding the wave of its 2009 stimulus program, which was significantly larger than the US’s as a percentage of GDP. India and China continue to grow rapidly in GDP terms, as do their carbon emissions.

However, as a result of the slowdown in economic activity elsewhere, global carbon emissions actually fell for the first time in 2009. And that raises an interesting point.

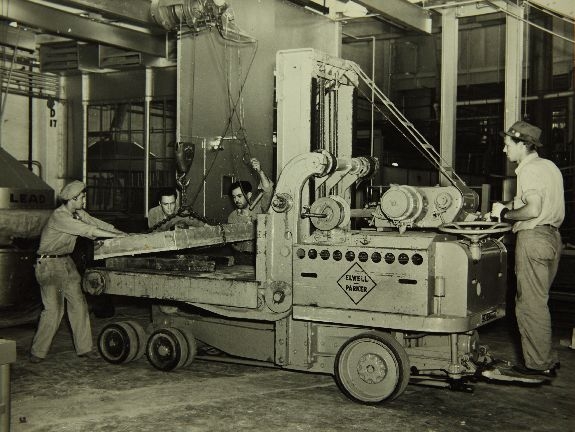

Since the Industrial Revolution, economic growth and fossil fuel use have always increased hand in hand. The Industrial Revolution was only made possible once rudimentary coal-fired steam engines were used to pump water out of mines so that miners could mine more coal. Eventually, the coal-fired engines improved and instead of just pumping water from mines they began to hull coal out of the mines and across nations and continents. The discovery of oil relieved the price pressure on coal, and ostensibly propelled the world into modernity. It even helped saved whales from extinction. Now there is the promise of unconventional gas.

While productivity and efficiency gains can be made in one area, the nature of the industrial economy ensures that most of those savings will eventually come back around to the consumption of or further investment in fossil fuel.

Despite the hopes of many that the economic growth of the past century can continue indefinitely without fossil fuel, there is nothing in the historical record to support why this would be so. Globally, increased fossil fuel consumption still means increased economic growth, and vice versa. Despite — or because of — the iPhone and financial derivative markets, this is still the Industrial Revolution.

Back in the summer of 2008, the price of a barrel of oil was at an all time high of $130 and global commodities from copper to wheat were at or near historic highs. Just as resource prices peaked, the home mortgage bubble finally burst.

After spending and printing billions to bail-out banks and stimulate growth, the economies of the "developed" West still stagnated, with tax revenues bottoming out and government debt spiking. But not before oil prices again rose to $100 a barrel and commodity markets reached new highs, primarily based on the speculation that China and India would in the near future consume more fossil fuel than ever before.

The predominant economic dogma preaches limitless growth and rewards greed, for lack of a better word. Cheap fossil fuels ostensibly create wealth that will circulate throughout the economy. That wealth eventually ends up in a bank, which eventually invests money back into the economy, or that is to say, the consumption and or exploration of fossil fuels. Yet it is increasingly evident that the dogma of limitless growth is reliant on finite fuels and resources, the burning and extraction of which do not create any real wealth. Just look at the all the debt. Not to mention the non-monetized environmental harm.

Our continued adherence to an economic growth policy reliant upon finite cheap fuels can at best be called idiotic. At worst, it is insane. GDP growth should not be a prerequisite for sustainability; instead, a change to the current economic dogma of growth is what is required for true sustainable development.