The Lives of Sex Workers in Modern China

Women hide their faces as police raid an entertainment venue in Beijing, China suspected of offering prostitution services. (China Photos/Getty)

When strolling at night through the streets of urban China, it usually doesn’t take long to encounter a massage parlor with a dim pink glow and scantily clad women waiting inside. The country’s sex industry is both illegal and ubiquitous, drawing millions of women — mostly from rural regions — to grab a slice of the massive wealth that has been created over the past decades (and disproportionately ended up in the hands of urban men).

In the new novel Lotus, Chinese author Zhang Lijia gives a window into the lives of these women by following the protagonist, a young woman from rural Sichuan who migrates to the coastal boomtown of Shenzhen, as she ends up servicing men in a red light massage parlor and navigating the travails of her profession and urban life.

Though the novel is fiction, Zhang drew on years of interaction with sex workers she got to know as a volunteer for an NGO that assists them with legal advice, education, and other support. By her estimation, through volunteering and conducting extensive interviews with women in prostitution meccas around China, Zhang spent time with over 100 sex workers and even accompanied some back to their rural hometowns to get a feel for their family dynamics.

In this interview with Asia Blog, Zhang discusses the real life women who inspired her novel and how the economic and gender dynamics in China have given rise to the country's massive sex industry.

How had the women you met usually ended up getting into sex work?

Quite a few women I interviewed worked very hard on production lines in factories for very little money. Then they talked among their friends and found out about jobs in massage parlors. In the beginning, the line is often blurred — some places offer legitimate massages and also sexual services, so women will start off doing normal massages and gradually start adding on sexual services when they see how much more money they can make.

Most women are migrant workers from rural areas, some are laid off workers from small towns, especially in Dongbei (China’s struggling northeastern region that’s now often referred to as a rust belt). There are also quite a few older women who are divorced or left abusive husbands and cannot otherwise support themselves. When they leave the countryside for the city, very few plan to get into sex work. It’s a hard decision in most cases. Sometimes it’s because of tragic personal circumstances.

Almost all of the women I knew sent money back to their families — it is out filial duty. One woman I met told me her brother was sent to prison so she supported her sister-in-law and her children for years. I think many of the women need something like that to feel good about themselves and the work they’re doing, so they send a lot of money home. I'm sure they struggle to come to terms with the work, especially since most rural Chinese women grew up with a very conservative upbringing.

I spoke with one woman who said in the beginning that she always used the phrase chi kui (to get the short end of the bargain) when talking about getting paid for sleeping with men. But then an older more experienced women told her, “Don't think like that, we're making use of them.” So she came to terms with it and now tells other women the same thing.

What role do you think gender inequality plays in fueling China’s sex trade?

In my book, Lotus has to stop her schooling because the family thinks they'll just end up marrying her off. Since she’s a girl, there's no point in wasting money on her education. Save the resources for the boy — that’s a common attitude in rural China, especially in the poorest areas. So rural women are generally much worse off than boys in terms of education. The political system, of course, is another problem. Because of the hukou residency system, rural residents still cannot apply for certain jobs. Economic reforms brought a lot of opportunities, but uneducated rural women really missed out.

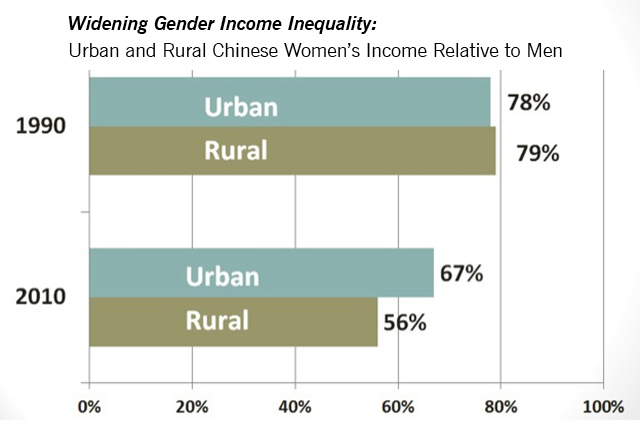

Ultimately, that’s part of why prostitution is such a big industry in China. With growing wealth and gender income inequality, I think concubine culture plays big a role. Men used to keep concubines and mistresses as a way to show prestige, and they still do the same. The growing wealth gap between urban men and rural women really magnifies this.

Source: All China Women's Federation.

Rural Chinese women once had infamously high suicide rates, which have fallen dramatically over the past decade — something researchers attribute partly to urban migration freeing women from the poverty and repressively patriarchal attitudes in the countryside, which, as you said, tend to view girls as bad investments that will just be married off to another family. Among the sex workers you got to know, did you sense any shift in attitudes or power dynamics because of their time in the city?

Absolutely. Of course, their families don’t know what they do, but they really enjoy the power brought by the money they make, and some improve their relationship with their family. I followed quite a few sex workers back to their village, and many had changed because of the city. They became far more assertive, criticized the family for things like throwing rubbish around or smoking. They can sometimes criticize rather abruptly and rudely, and why are they able to do that? It’s because they bring money home.

I find it quite interesting how many of these women are anxious about flaunting their success when they go back home. I went with one woman back to her village and when we arrived, she put on high heels, fashionable clothes, and went out of her way to attract people's attention, to show off her success.

The image of a prostitute’s life being utterly miserable is not quite the case. In addition to the power brought by the money, they also often have fun with one another. There are very close bonds among sex workers. Of course, there’s some jealously, but they work together and really support each other. They enjoy what the city has to offer, like different exotic foods.

Some of them enjoy the men's attention — some get sexual pleasure that they have never had with their boyfriends or husbands. It's a very complicated situation, not just total misery. Some people think that in China, sex workers are mostly trafficked and forced into prostitution by pimps. But in fact, most women work of their own free will.

One theme of the book seems to be the strong sense of class status that separates urbanites and rural migrants. How did this manifest itself in the sex workers you got to know?

Generally speaking, urbanites and migrant workers in the city live parallel lives. Among these women, there’s almost an unconscious desire to be accepted by urban women and be like them.

I interviewed some women who had previously worked as waitresses or domestic helpers and constantly got shouted at and demeaned. Some women said they actually felt more appreciated doing sex work because of the greater money and attention. For example, some women were quite flattered that clients called them sweet terms of endearment and gave them flowers or other expensive gifts, which their husbands would never do.

Chinese feminist and LGBTQ activists Li Maizi (Li Tingting) and Di Wang, along with journalist Barbara Demick, discuss progress in women's equality and gay rights movements in China. (1 hr. 18 min.)

What were the biggest dangers faced by the sex workers you talked to?

I heard terrible stories of women in the “custody and education” system (a penal system for prostitutes that can force them to labor in camps for up to two years without trial).

Of course, violence from clients is a risk for sex workers, but there’s even more violence from the police. Police will raid their establishment, arrest them, then if they need a confession, they’ll often beat the woman up to get it. I heard stories of police spraying women with high-power water hoses. One woman threw up and was forced to eat her own vomit. Another was beaten to unconsciousness, so they put mustard up her nose to wake her up.

They'll say, “if you confess, we'll let you go,” but when the woman confesses, she can be punished. So the NGO I worked with tells these women never to confess. The first time they may just warn you, give you a fine, and a few days detention. If it’s really serious they can send you to a labor camp to work for two years. One woman had to sleep with a policeman to be let go, then he still demanded another 2,000 yuan ($290) bribe to finally let her go. But one of the worst things they can do is send the woman back to her hometown and expose her. If a woman’s family finds out about her sex work, she could be disowned.

When I was working at the NGO, a woman was arrested and other sex workers really tried to help her. They reported it to the NGO and some chipped in money to bail her out because they knew she might be returned home and exposed. They really supported each other.

Another problem created by these police crackdowns is that sometimes condoms are used as hard evidence, so some prostitutes don’t dare carry them. There is some support for legalizing prostitution in China or setting up special legal red light districts, which could solve some of these problems and reduce sexual violence on sex workers, but as long as China calls itself a “socialist country,” it is quite impossible to fully legalize the sex trade. So realistically some experts have called to decriminalize it, and in particular, abolish the 'custody and education' system.