Kevin Rudd's China Journey

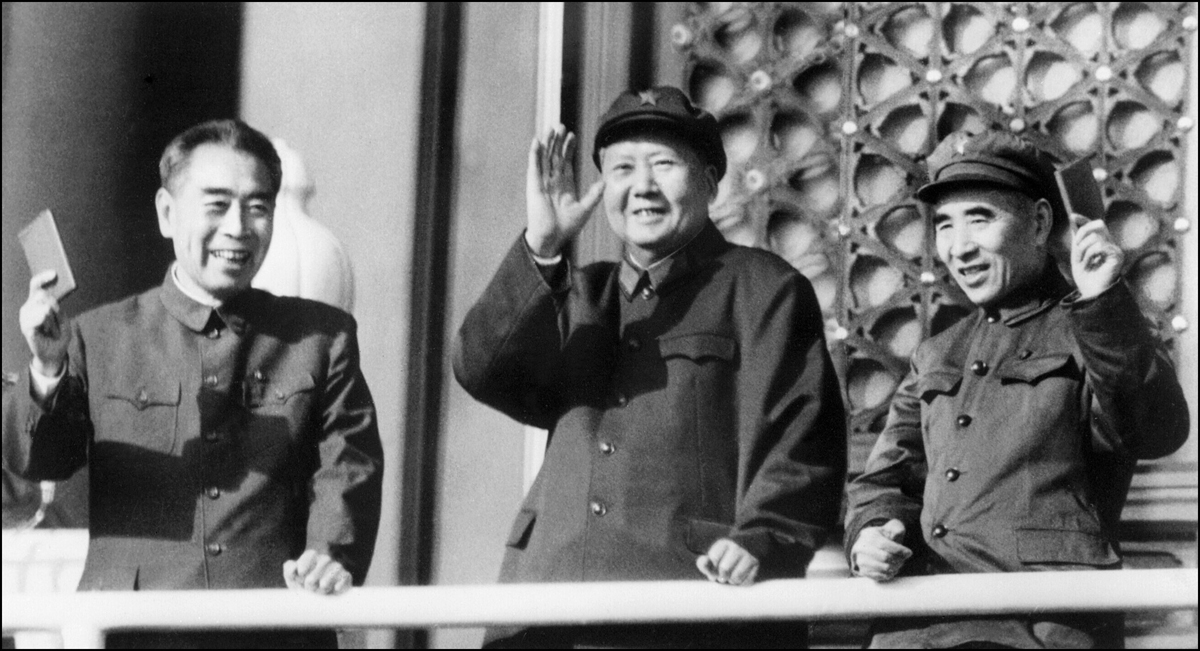

From left: Chinese top communist leaders Zhu Enlai (1898-1975), Prime Minister of the People's Republic of China from its inception in 1979 until his death, Mao Zedong (1893-1976), leading theorist of the Chinese communist revolution, chairman of the party and President of the Republic, and Lin Piao (1907-71), minister of defense and supporter of the Cultural revolution, wave 03 October 1967 at Tiananmen Square in Beijing the 'Little Red Books' as they review troops celebrating the 18the anniversary of the Republic. (AFP/Getty Images)

AFP/Getty Images

When Kevin Rudd became prime minister of Australia in 2007, he achieved recognition for possessing a skill unique among leaders of a Western country: fluency in Chinese. Now based in New York, where he serves as president of the Asia Society Policy Institute, Rudd has emerged as one of the world's most sought-after experts on China and is a widely published author of scholarship and commentary on the U.S.-China relationship.

In this excerpt from his recently published memoir Not for the Faint Hearted, Rudd describes his lifelong fascination with a country he first encountered as a young man and knew, despite its poverty and years of chaos, would play a vital role in world affairs thereafter.

My reasons for choosing to study China were simple: The country had fascinated me since childhood, because it was so vast, so old and so different. I liked the relatively few Chinese people I had met, and I thought China would have a major impact on my country’s and the world’s future. I wanted to make a difference in our understanding of China, and someday I wanted to work there, although in what capacity I had no idea. Not much has changed in my thinking since, although there is now something of a greater global urgency about "the China question" than there was back in the dying days of Mao’s "Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution."

Just after finishing my university studies, I read a short book written by the father of Australian Sinology, C.P. Fitzgerald. By the time the book, Why China, was published in the early 1980s, Fitzgerald was almost 80 himself. He had resolved as a 13-year-old, near the end of the First World War, to travel to China, and done so at the age of 21. He had gone on to live there for nearly 30 years, during the most tumultuous period in modern Chinese history, all as part of a lifetime of scholarship dedicated to the Western understanding of the Middle Kingdom. His answer to the question posed in his title in some respects speaks for the generations of Sinologists that followed and preceded him, going back nearly 400 years, to the father of Western Sinology, the great Italian Jesuit Matteo Ricci, who first set foot in the China of the late Ming emperors. As C.P. Fitzgerald wrote:

Here was a vast world of fascinating history of which I knew nothing whatsoever: it did not enter the school curriculum at all (a strong point in its favor). As far as history at school was concerned, China did not exist, except for a very brief, totally one-sided and largely inaccurate mention of the Opium War and the Boxer Rebellion. It was a field of interest wider and deeper than the Balkans; unknown, but absorbing ... China was the thing: from that very day I began to look in my father’s library for books on China.

What had stunned even the most culturally literate of Westerners over the centuries was the antiquity, continuity, sophistication and sheer scale of Chinese civilization. This was reinforced by China’s not unreasonable claim, when tested against the historical evidence, to be a complete, self-contained and exclusively self-referential philosophical, political, ethical and aesthetic system, as if the rest of the world simply need not have existed at all. Together, these deep characteristics of Chinese civilization have caused generations of Western intellectuals to conclude that in China there lay an as yet undiscovered world of the mind and one which had often reached conclusions about the nature of human society quite different from our own. As ancient as classical Egypt, but unlike Egypt, retaining for over 4,000 years its ancient pictograms as modern characters, producing the largest literary inheritance of any language on earth.

A territory as vast as Europe, but for the main part comprising just one nation. Also a philosophical system as old as, and in some cases older than, classical Greece. And with the single exception of the absorption of Indian Buddhism, its principal philosophical schools representing almost exclusively indigenous debates, evolved within the confines of the Middle Kingdom itself, and its principal subject matter, internal delineations and conclusions settled well before the dawn of the Christian age. And all this in contrast to the untidy, but ultimately stupendously creative amalgam of Greco-Roman, Judeo-Christian and Enlightenment beliefs and practices that evolved into the modern phenomenon we now call the "idea of the West."

China, by contrast, had evolved as a unified, civilizational state rather than as a conscious political construct across different cultures, ethnicities, religions and forms of government. For these reasons, the study of China was seen by Western scholars as so vast an area of inquiry, and one so alien to the traditions of the West, as to command a combination of deep intellectual respect, profound professional passion and often a lifetime of scholarly vocation. Not to mention the excruciating frustrations experienced by the Western academy when the subject in question, namely Chinese civilization in all its unity and complexity, did not readily yield its deepest codes to foreign, scholarly fascination, however earnest.

Once the doors of this cultural universe are slowly unlocked by the keys of its forbidding language, the Sinologist can often become so consumed by this self-contained universe that a number of patterns of analysis, some would say pathologies of analysis, begin to unfold. One is when an unhealthy level of civilizational "awe" takes over as Western critical faculties are progressively suspended, and neither China nor its civilization are any longer capable of human error. These scholars see their mission as explaining, even evangelizing, the uniqueness of the Chinese civilizational perspective to the uninformed world of the foreign barbarian. Cultural or ideological capture is not unique to the study of China, but over time China has generated more than its fair share of the global caseload. A radically different pattern of scholarly response sees China written off as a fundamentally authoritarian culture, both in its classical past and its contemporary form, with nothing of value to offer the world today other than the monetary value of its markets. A variation on this response is one that holds ancient Chinese civilization to be sublime, but its modern equivalent to be nothing less than a course in cultural desecration, from the physical iconoclasm of the Cultural Revolution, through to the mass, materialist and characterless culture of the early 21st century. In other words, in the wide, wide world of Western Sinology, we see the full menu of Western ideational and emotional responses to China — from uncritical admiration to visceral contempt and/or profound disappointment.

Over the last 400 years China has attracted an army of Western missionaries, both secular and divine, and sometimes a curious combination of both — the former seeking to understand and then explain China to the rest of the West; the latter seeking to explain the West, and its God, be it Christianity or capitalism, to China, and if possible to remake China in the West’s own image. Four centuries later, the mutual non-comprehension between these two great civilizational traditions remains, despite the efforts of a small legion of British, American, French, German and Australian Sinologists, academics and officials, and their Chinese counterparts, most particularly over the last 150 years since China first fully opened its borders to the West, to somehow bridge the yawning chasm between the two.

A minor battalion of Westerners in fact worked as official advisers to various of the Ming and Qing emperors and later to the leaders of the fledgling, faltering Chinese Republic. Many of these foreign advisers, if you read their contemporary accounts with a generous and sympathetic cast of mind, were deeply committed to helping the cause of China’s political and economic modernization, so that China could once again stand up as a proud civilization against further foreign humiliations, especially against the fresh aggressions emanating from Japan in the half-century from 1895 until 1945. Perhaps these advisers were driven by their own sense of remorse, having seen the damage and destruction inflicted on China by their own countries, starting with the sheer obscenity of the Opium Wars, culminating in the West’s betrayal of the young Chinese Republic at Versailles, when the Allies refused to return Germany’s former Chinese colonies to local sovereignty after the Great War. These well-intentioned foreign advisers ultimately failed in their mission, as reflected in the Japanese invasion, which they were powerless to prevent. With the subsequent victory of the Communist Party in 1949, China neither trusted nor welcomed any further advice from the West. At least not until Deng’s decision another third of a century later to turn once again, albeit only in part, to the West to help negotiate the country’s current successful economic modernisation program — this time, however, without Western advisers within the Chinese court, where profound suspicions ultimately remain about the incompatibility of Chinese and Western views of the world.

It is into this complex minefield of conflicting Chinese and Western historiographies of China itself that the unwitting undergraduate student of Chinese walks on his very first day at university, soon after to be seen roaming the campus and wondering aloud: ‘What on earth have I done?’

Learning about China and its language had, at the time, little to do with any of the arguments rendered above. These, in the main, represent cumulative reflections on the actual study of China over the many years since I attended my first Chinese class back in 1976. But they do say something of the intellectual environment in which I was to study for the next five years of my life.

As it turned out, 1976 was not to be your average year in Chinese politics. The death of Zhou Enlai in January was followed by unprecedented, spontaneous public demonstrations in Tiananmen Square in April in honor of his memory. The Great Tangshan Earthquake in July killed up to three-quarters of a million people not far from Beijing, evoking a belief among China’s vast peasantry that such a tumultuous natural calamity heralded impending dynastic change. September saw the death of the great helmsman himself, Mao Zedong, and the purge of the ultra-leftist Gang of Four in October, followed by the formal conclusion of the 10-year-long Cultural Revolution (a civil war by another name) by year’s end. So as we undergraduates struggled with our tones in the language laboratory, Chinese politics was turned on its head in the most momentous year in the history of the People’s Republic since its founding. Outside the language lab, we sat through grand public debates between the Maoist, the anti-Maoist and the "neither Maoist nor anti-Maoist, let’s see how all this turns out in the end" factions among faculty members. They were heady days for those of us struggling to pronounce Mao’s name correctly, let alone understand whether the helmsman had been a revolutionary hero or political mass-murderer, or sat somewhere along the considerable spectrum in between.

The truth was no one had any real idea what was going on in Chinese politics at the time. Understanding internal Chinese politics then was like understanding North Korean politics today. Opacity was the polite understatement. Conjuring images out of the darkness was nearer the mark. We squinted at hand-held video footage of the Tiananmen demonstrations in April 1976, smuggled out by a returning student who’d had a Kodak Super 8 camera lens hidden between the buttons of his massive PLA green overcoat. Our interest, imagination, engagement and excitement were spiked by our minor academic connection to the great events unfolding to our north and proximity to professors who had made Sinology their lifelong vocation. We were on our way to becoming, we hoped, bona fide "China-watchers," a term of art for those in the post-1949 academic and intelligence communities who tried to make sense of what was going on in China, when China, ensconced behind the Bamboo Curtain, had made it their business to prevent the world from finding out. There was no better year than 1976 to have begun our study of China (1977 turned out to be quite a downer by comparison) and as undergraduates we all wanted to understand more, some of us with a giddy sense that we were embarking on a truly grand enterprise.