Interview: In Yangon, Photographer Andrew Rowat Finds a 'Future Yet Unwritten'

Asia Society Museum’s history-making exhibition, Buddhist Art of Myanmar, opens February 10, 2015, in New York. Exploring Buddhist narratives and regional styles, Buddhist Art of Myanmar is the first exhibition in the West to focus on art from collections in Myanmar. Learn more

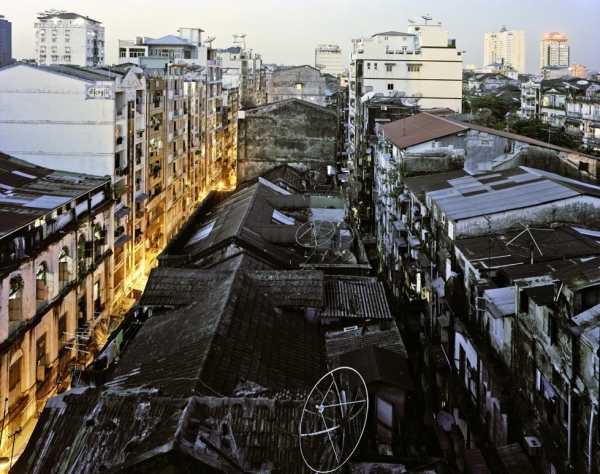

Andrew Rowat is a photographer based in New York and Shanghai. He has been traveling to Myanmar since 2012, and is documenting the nation’s transition in the project Collision Yangon.

Rowat communicated with Asia Blog via email to share a few insights into his experiences in Myanmar and into what motivates his current project.

You first visited Myanmar in October 2012 with WSJ Magazine. Could you tell us about that first experience? What drew you specifically to Yangon?

For the initial project in 2012, I worked with writer Tony Perrottet, who had first proposed the story to WSJ Magazine. We traveled to Yangon, Bagan, and Inle Lake and focused on architecture, particularly in Yangon.

I was drawn to Yangon for a host of reasons, but the primary one was the gorgeous crumbling architecture of the city. Yangon has been in a time bubble for almost five decades, and is only now emerging from the glacial weight of military dictatorship. At the same time, it is a place in flux, particularly with elections looming at the end of the year.

Yangon reminded me in some ways of Shanghai, my home for almost eight years. In both cities, you can find old British colonial architecture clinging to a riverbank. Both cities also had an undeveloped tract of land across the river (in Shanghai, this is now the Pudong Financial District). I was sensitive to the energy of change. And Yangon is changing at a rapid clip, far outpacing the rest of the country. So for me, that is where the draw was strongest.

What’s so unique about Yangon’s architectural heritage, and what’s challenging about preserving it?

Architecturally, Myanmar is unique in that it has been fostered by the decades of isolation from the world, and is only now opening up on a magnitude that has not yet been seen. It’s like you have this smoke that has been trapped in a bottle for close to 50 years, and the stopper has just been removed. There is a moment in time here before everything is reconfigured, changed, developed, and paved over. It’s a challenge that any city faces: balancing the needs of development, the needs of the individual people who are living in these aged buildings, and the aggregate benefit that the city as a whole derives from this preponderance of amazing architecture.

Andrew Rowat at Inle Lake, Myanmar. (Lee Satkowski)

It comes down to very basic give and take. Imagine you are a person living in a "gorgeous" heritage building, but it hasn’t seen any sort of repairs or upkeep in decades. Then a developer approaches you and offers to pay you a grand sum to leave and move outside the city core. This can be a pretty attractive offer: an updated washroom, running water, and kitchen — essentially, a move toward a more comfortable middle-class living situation.

It’s hard to argue with someone who sees how his or her own life can be improved. But it comes at a cost — that the city itself loses some of its unique DNA. And it’s very difficult to come up with funds to restore and maintain these heritage buildings.

That, of course would be the best situation: restoration of all of these amazing places, and the people living there would get to stay. But it’s probably not realistic for all of the buildings. There is too much money in play and headlong development coursing forward. The Yangon Heritage Trust (YHT) has done yeoman’s work in making a real impact — building preservation, working with local government to enact regulations (including a historical core for the city), and a myriad of other initiatives. They are the group to watch in terms of what sort of progress is made on the preservation front.

You’ve traveled extensively in Asia. What did you find unique about Myanmar, and what are some of the themes you highlight in your work?

The title of the work is Collision Yangon, and it explores the forces that are currently colliding in the crucible that is Yangon. You have opposing forces of so-called modernity and development pressing up against traditional ways of life; new buildings displacing old; religious tension between Buddhists and others (mainly Muslims); political uncertainty as dictatorship transitions to a form of hybrid democracy; and the energy of the place — roiling currents of optimism and unbridled hope for a future yet unwritten.

That unwritten future is one of the main themes of my work as well. Yangon, and Myanmar as a whole, stands at a crossroads where it has the power (and hopefully the wisdom) to chart a path forward that benefits all of their people.

How has your experience in Myanmar changed you, both personally and as a photographer? Looking ahead, how are you hoping to stay connected to the country?

I am going to keep going back to photograph, and Collision Yangon will eventually become a book of the same name. As a photographer, this experience has forced me to evolve in my framing. I used an 8x10 for the first time on this project. It is a format that slows you down and forces you to fill the whole frame.

My "day job" is as an editorial photographer, and magazine photography demands an aesthetic where you might make accommodations for text and titling. But on my own projects such as Collision Yangon, I am forced to account for every square inch of the photo. It is a wonderful imposition and way of working. It has bled into my editorial and commercial work as well, and created a more measuring approach to why I am including or excluding an element from the frame.

On a personal level, the experience has reminded me of the importance of always traveling with Imodium.

Video: Collision Yangon time-lapse (3 min., 0 sec.)

Video: A brief explanation of Andrew Rowat's Collision Yangon project (5 min., 0 sec.)