Interview: Meet Wu Tong, China's Musical Polymath

On March 19, Asia Society presents Wu Tong: Song of the Sheng, part of the Asia Society Performing Arts program and the Asia Society’s Center on US-China Relations’ ongoing “US-China Forum on the Arts and Culture.” Learn more

Wu Tong has long been one of China’s most versatile musical figures, both at home and abroad. The son of China’s most prominent wind-instrument maker — and the man responsible for modernizing traditional instruments for the 20th century — Wu has shaped Chinese music in the 21st century in ways that might well have shocked his late father.

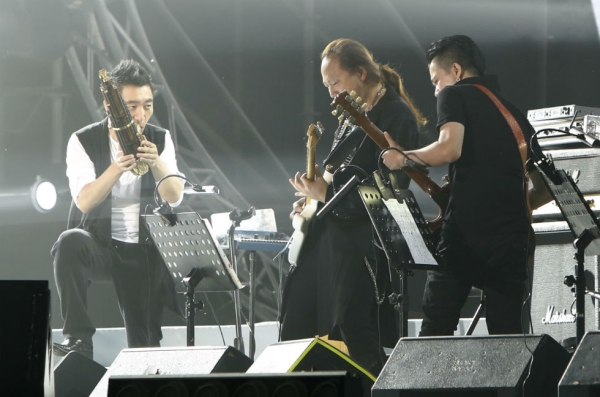

Having been showcased in his childhood as a national–level wind virtuoso, Wu and a handful of conservatory colleagues formed Lunhui, a rock band in the model of Cui Jian and other groundbreakers in China’s protest rock movement. In 2000, they became the first rock band to appear on China Central Television. That same year, Wu became a founding member of Yo-Yo Ma’s Silk Road Ensemble. Most recently, Wu and Ma, along with the New York Philharmonic, performed a piece appropriately entitled Duo, composed for them by the Beijing-based composer Zhao Lin.

While in recording sessions last week for the Silk Road Ensemble, Wu Tong took a few moments to answer questions from Tim Lau, an editor for Asia Society’s Asia Blog, and Ken Smith, Asian performing arts critic for the Financial Times. Joanna C. Lee, founder of the arts consultancy Museworks, Ltd, provided translation assistance.

You studied many Chinese wind instruments. What was it that attracted you most to the sheng?

I didn’t choose the instrument, my father did. Since the sheng is an instrument with fixed pitches, he felt that it would be a better choice for my ears as far as precision was concerned. As I continued with my music career, especially in singing, that kind of pitch training clearly helped me. For a while, I felt the sheng perhaps wasn’t really my ideal instrument — that our relationship was actually not compatible, since the sheng seemed a bit “cold” for my own temperament. But as I grew older, I seemed to have found the spirit of moderation and it all felt exactly right.

Your rock band Lunhui certainly wasn’t “cold.” How did you go from a traditional conservatory education to forming a metal band?

When China reopened in the late 1970s, I first came into contact with American country music. Then there were Teresa Teng’s Hong Kong/Taiwan-style pop songs. We got all kinds of music on cassette tapes. Only later did we learn about rock. But by the time we formed our own band, we were particularly interested in copying the music and style of Aerosmith, Bon Jovi, and the Scorpions.

Your music has crossed so many boundaries. Do these feel like separate entities, or do you bring elements of rock music to traditional playing, and something of Chinese tradition to rock music?

When I’m singing, I use a very traditional approach. Sometimes it takes a long time — anywhere up to a month — to learn and refine a single song. I’d go to the park in the morning to practice singing just that one song.

Even when we were writing rock songs, we still used harmonies and vocal styles that we learned from traditional Chinese music. In rehearsal, we’d notate the songs in the traditional manner. In particular, we all felt it was important for the band be rhythmically precise. And after a while, we realized that the standards we set for ourselves apply to all music, not just traditional, not just rock.

Looking back at 15 years with the Silk Road Ensemble, what are some of your most vivid memories? Has it changed you as a person and a musician?

Because of working with so many musicians, I’ve also learned about different countries, different languages, different cultures. Through my instrument, I’ve learned much about the expressive powers of language.

More importantly, though, I learned about respect. The Silk Road Ensemble is a big family, and we take care of each other. We understand each other. When I started, I had absolutely no English. All of them are actually my English teachers!

At the same time, I’ve played host to many of my friends or their family members when they visit Beijing. And when I travel around the world, I also have family and friends everywhere — in India, in Iran, in America. After years of traveling around the globe, we feel very close. We accept each other’s differences, and by accepting others we show how they can accept us. Again, the key is respect.

Could you compare the artistic climates in China and the U.S.? How are the challenges different?

Both countries have given me great opportunities and great experiences. On the negative side, the Chinese music market isn’t as mature as America’s. You can’t find much that’s experimental or even crossover within traditional Chinese music. In America, the environment is much different. America is much more respectful of art and artists. In America, you find many different ways to express music.

On the positive side: China is my home, my family, where I was born and grew up. In China, I have inspiration for creation. In the West, Chinese traditional music is still not commonly known, and few people really understand many of the music’s wisdoms and ideas. For me, finding a contemporary language requires a certain cultural grounding.

You have two new pieces for Thursday's program: Distant Mountain and Harmonium Mountain II. Can you give our audiences an idea of what to expect? Also, tell us about your relationships with Eli Marshall and Clifford Ross.

I created Harmonium Mountain II three years ago with Clifford Ross, an artist who always seems open and willing to move forward. This was the second version of his piece. Our initial collaboration was for sheng and cello, but we worked on several versions to see how they fit with visuals. Since the video animation was created out of a single photo, we found it was most appropriate — though more challenging — to match the video with a single instrument.

Distant Mountain is about ancient spirit. The sheng is a very traditional instrument, found in both Confucianism and Taoism. The spirit of moderation is about being in harmony with nature; nothing can be forced. The sheng can express this beautifully. Traditionally, sheng music is very slow, and this too is a slow-moving piece, very simple in expression. Eli Marshall, who did the arrangement for this program, has lived in China for many years. We are very good friends. When the film director Wong Kar Wai asked me to write music for his film Ashes of Time Redux (2008), Eli became my co-composer. In his new score for Ann Hui’s film Golden Era (2015), Eli again asked me to perform. Eli has a very clear grasp of Chinese music, and does particularly well with the sheng’s subtle qualities.

What is the new generation of musicians like in China now?

I know many young artists, though I don’t feel connected with many of them personally. In pop musicians, I notice a strong passion. They have open minds, and they want to say something socially conscious. And, of course, at that age they want to be very successful. But I don’t think their heart is deeply cultural, because they don’t even know who there are yet. Particularly in rock and pop, this is something they find out along the way.

In traditional music, my generation was one of the last to have genuine roots. Of course, I had a family mission; I didn’t have a choice. But I had an older generation who could answer questions, and could see how the music was connected to the culture. With China’s modernization, most of that is lost. The new generation only knows the printed repertory. They can read only what’s on paper, not what’s in the soul.

The Wu family has a long history of both preserving musical heritage and revolutionizing it from within. Do you consider yourself a traditionalist who’s constantly evolving, or a revolutionary grounded in tradition?

You know the famous black-and-white Taoist symbol, with the yin and yang? Even in the black you can see also a little bit of white, in the white is still a little black. In the same way, the past always has some of the future, and the future a bit of the past. Sometimes, I’ve found myself paying all my respects to the heritage. Sometimes, I’m concerned only about the future. It took years for me to find moderation. Like yin and yang, the past and future come together to make the present. Directly between past and future is now, and for me, the “now” is most important.

Tim Lau, Ken Smith, and Joanna C. Lee contributed to this interview.