Interview: Jonathan Spence on the China-India Relationship

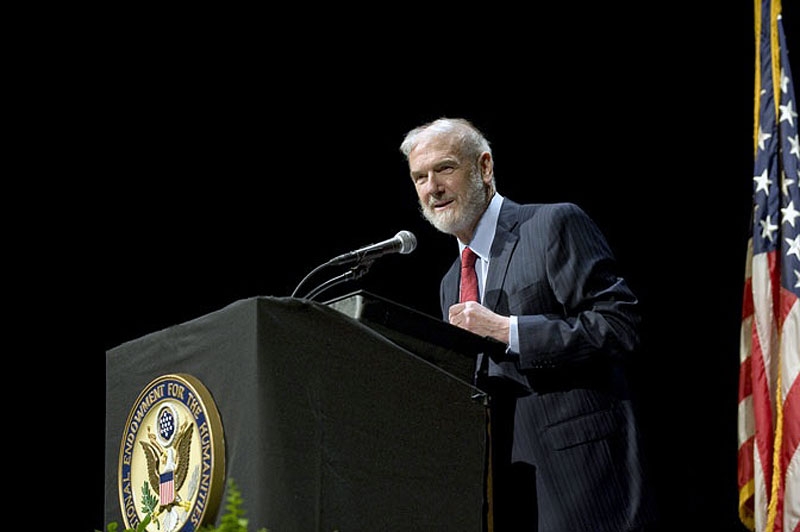

Throughout his long career, historian and author Jonathan Spence has emerged as one of the most distinguished living chroniclers of modern Chinese history. In particular, Spence has specialized in the way China interacts with foreign cultures, a subject that has informed books such as The Memory Palace of Matteo Ricci and The Search for Modern China. Spence is Professor Emeritus at Yale University, where he was the Sterling Professor of History from 1993 to 2008.

On Thursday, November 3 Spence will appear at Asia Society New York in conversation with the Indian novelist Amitav Ghosh, whose latest novel Rivers of Smoke was published this month to wide critical acclaim. Spence and Ghosh will discuss the history of Sino-Indian relations and how this relationship will evolve in the coming years. The conversation is part of Asia Society's Chindia Dialogues (Nov. 3-6) and will be introduced by Center on U.S.-China Relations Director Orville Schell, will last from 6:30 to 8:30 pm. Unable to make it to the show? Be sure to tune into the free webcast at asiasociety.org/live.

Asia Blog recently had the opportunity to speak with Jonathan Spence about the historical nature of the Sino-Indian relationship and how the two countries may interact in the future.

Prior to independence India was administered as a colony, while China, though nominally independent, was compromised by a number of foreign incursions. How did these historical experiences affect India and China’s independence in the second half of the 20th century?

Well, there could be a lot of arguments about whether India was a colony, strictly speaking, but that's another whole issue. With regards to which parts of the country were dominated by British economic or by Indian allies, the whole history of India in regards to the British is a gigantic complicated saga, I feel, especially of course with the partition and then the separations of Pakistan and Bangladesh. China has a very different kind of relationship. Because British control through international means — the central treaty port system or the unequal treaty system — was limited to very limited pockets in China, I guess you could say that the British were more widely spread throughout India than they ever were in China. Plus the Indian relationship with China has of course been much earlier than either ever was with the British, going back to the early Buddhist period.

We know that India and China have had fairly acrimonious relations during the second half of the 20th century. Will these relations improve going forward or will they continue to be difficult?

I don't think relations will be forced to be acrimonious. There are areas of major disagreement, not necessarily the most strategic and largest areas on the planet by any means — largely distinctions of who controls which exact pieces of some southern Tibetan highland — I don't think for either India or China the stakes are necessarily huge, and I don't think there's any need for them at all to be particularly difficult. Relations with Tibet may be part of the story, the exile of the Dalai Lama may be part of the story, previous British history and Russian history in the region has something to say about this, and India's cultural power as expressed through Buddhism has also had ongoing impact.

But in comparison with other areas of Chinese border politics like Myanmar, Korea, Taiwan, parts of western Xinjiang, Vietnam, these are all more potential flashpoints than India itself.

Do you think there's a possibility for a sort of pan-Asian identity that links India and China, or are the two countries simply too different to forge a common identity?

That's difficult to answer, but I think there might be possibilities of new kind of alliances or affiliation we haven't really thought of yet. One discussed occasionally over the last two or three years was whether China in terms of international market politics isn't in a sense two enormous zones already, each with its own spheres of influence with neighboring countries. One could imagine a northern China trade zone including Beijing and Tianjin and Northeast China along with Korea and Russia, and perhaps even Xinjiang in the far west. This could be a very powerful bloc, partly led by China but also partly autonomous in terms of the member border countries. If there were such a northern bloc that would harness productivity capacity in northern China, then that might make for a logical structure.

That might be balanced with a southern China region which would take more interest in Myanmar and Vietnam, with perhaps at some future date would include more trade with Japan and Southeast Asia, perhaps even deeper trade ties with Taiwan. That southern bloc might spread from Myanmar into northern India and link into more global regions. This is utterly speculative, but different kind of arrangements might be possible.

Do you think that environmental concerns such as water scarcity, an issue as many of India's great rivers begin in Tibet, could that play a role going forward?

I think that they definitely could, but I'm not an expert on the water situation except to know that it's regarded as a very serious problem. China has backed away from one or two dams recently that might have had an adverse effect. But the feeder water supplies for the Yellow River are already badly compromised, and southern water flows interrupted Yunnan and Tibet become very important. I think water politics will become an international regional problem.