Interview: Author Blaine Harden on North Korea's Gulags

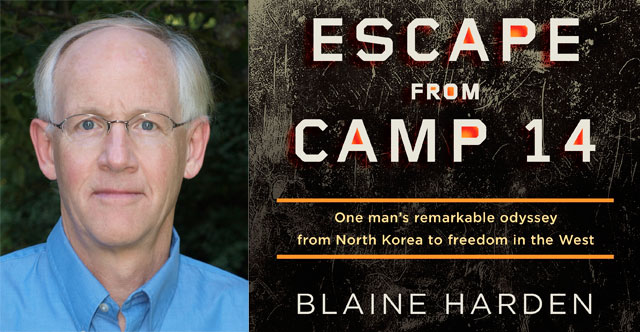

Blaine Harden and his new book 'Escape From Camp 14.' (Blaine Harden photo by Blake Chambliss)

North Korea houses a vast network of forced labor camps, where it is estimated between 150,000 and 200,000 men, women, and children are imprisoned and often worked to death. A new book by journalist Blaine Harden, Escape from Camp 14, tells the story of Shin Dong-hyuk, who is the only person born and raised in a labor camp known to have escaped and to tell his story. Harden’s book puts a personal face on the suffering and brutality of the camps, contrasting Shin’s miserable existence with the charmed life of Kim Jong-un, who recently succeeded his father as Supreme Leader of North Korea. Harden, who has written for The Washington Post and The New York Times in Africa, post-Communist Eastern Europe, and East Asia, interviewed Shin over two and a half years in South Korea, Southern California and Seattle.

Asia Society Northern California will host Harden at an event on Wednesday, July 11 in San Francisco to discuss his new book. Co-organized with the World Affairs Council of Northern California, the event will be moderated by Philip Yun, Executive Director and COO of the Ploughshares Fund. Copies of Escape from Camp 14 will be available for purchase and signing by the author. Click here to register.

Harden recently spoke to Asia Blog about how he reported Shin’s story, human rights in North Korea, and the future of the Kim dynasty.

North Korea’s labor camps have not received much attention in the West. Why did you decide to focus specifically on Shin’s story, rather than writing more broadly about the history and conditions of the country’s labor camps?

I focused on Shin’s story because it is irresistible, even for readers who know nothing about North Korea. It is an escape adventure, a story of a profoundly dysfunctional family, a story of the awakening of a young man to his own humanity. And of course it is a fascinating and horrifying window into the operation of North Korea’s gulag.

One of the central dramas in the book is Shin’s revelation that he informed on his family. When he revealed this to you, he refuted his previous accounts of the episode, including in his memoirs. How did this come about? Was it because you were able to gain Shin’s trust, or was he just ready to come clean?

Shin surprised me when he said he had been lying about his role in the death of his mother and brother. As I wrote in the book, he decided to disclose his lie because he was surrounded in Southern California by people he trusted. He believed they were trying to help him. He was feeling increasingly guilty and ashamed of what he had done as he learned more and more about what “normal” relations are supposed to be between a son and his mother. I do think he wanted to come clean.

In your book, you suggest that it is difficult to ensure the North Korean people receive adequate food, medical, and fuel aid without unintentionally propping up the regime. How can the international community strike this balance? Is it possible to have effective sanctions without starving North Korea’s people?

I don’t know the answer. U.S. food aid clearly helped save the lives of tens of thousands of North Koreans in the late 1990s and helped end a catastrophic famine. But food aid has been — and seemingly always will be — diverted by the North Korean government to feed the army and the elites. I guess the aid should be limited, except in the case of a catastrophe.

Your book has received a lot of attention in the West. Have you seen a comparable reaction in East Asia, particularly in South Korea and China? Do you feel it has led to greater awareness among Americans of human rights abuses in North Korea?

The book is to be published in coming months in Japanese, Chinese (not on the mainland), and Korean. We shall see the reaction. I do think it has helped raised awareness in the U.S. and Europe, in part because of coverage in The Washington Post, the New York Times, and the Economist. It is the power of Shin’s amazing story that works to hook the interest of news media and readers.

South Korean President Lee Myung-bak recently told U.S. Rep. Ileana Ros-Lehtinen, chairwoman of the House Foreign Affairs Committee, that human rights issues in North Korea are more urgent than stopping the country’s nuclear program. Do you agree?

Yes, I do agree. The nuclear program is of course worrying and deserves attention. But the human rights issue is an ongoing crisis that every day cripples the lives of millions: One third of the North Korean population is chronically hungry, with widespread stunting and cognitive impairment for infants. The camps continue to starve, torment, and work people to death. There is no rule of law.

What role can the U.S. play in promoting human rights in North Korea? Do you see China as enabling human rights abuses in North Korea, or could China potentially exert influence on the regime to curb these abuses?

The U.S. can make human rights a part of every conversation it has with North Korea and with China. This hasn’t been the case in the past. There is, of course, a limit to what the US can do. Leverage on China is also limited.

Besides telling a compelling story, what do you hope your book achieves?

Raise awareness of the existence of the camps and of the misery that continues to go on inside them. I hope that this will lead to popular and political pressure on the U.S. government to make human rights a part of diplomacy with North Korea going forward. This is also Shin’s goal — in agreeing to do the book.

You covered Eastern Europe after the collapse of the Eastern bloc. Do you think there are any lessons for North Korea? Do you foresee a nonviolent end to the regime?

The Kim family is said to have paid close attention to what happened in 1989 to the Romanian dictator, Nicolai Ceausescu and his wife. They were lined up against a wall and machine-gunned to death. Many analysts (at the CIA and elsewhere) believe that the hard line maintained by Kim Il Sung and Kim Jong Il was the result, at least in part, of that messy business in Bucharest. Kim Jong-un may think differently. It is now too early to know.

The soft landing that seems possible to me is for Kim Jong-un to allow gradual Chinese industrialization of the North. Factories could give North Koreans real jobs with real pay (at salaries much lower than in China). With hard currency in the economy, food could be imported. This would quickly solve the greatest human rights problem in the North, which is widespread hunger. There is then the possibility of gradual change along the lines of what we have seen in Vietnam or even China.

Going this route would reduce the chances of a regional war, reduce the chances of a sudden collapse in the North that would send refugees into China and South Korea, and reduce the chance that Kim Jong-Un would one day be shot. So far, though, Kim the youngest has not demonstrated any interest in opening North Korea to Chinese business. Indeed, in his first six months he seems to have gone out of his way to irritate his indispensable patron. I cannot say that I understand why.

Asia Society Northern California will host Harden at an event on Wednesday, July 11 in San Francisco to discuss his new book. Click here to register.

Reported by Xiaoxiao Li and Jameel Naqvi.