magazine text block

Before becoming vice president at the Asia Society Policy Institute, Wendy Cutler spent decades working as one of the United States’ top trade negotiators. During that time, she helped draw up some of the most significant trade agreements inked between the U.S. and Asian nations. Cutler was chief negotiator to the U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement, which was signed in 2007, and served as a senior negotiator for the Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP) during the Obama administration.

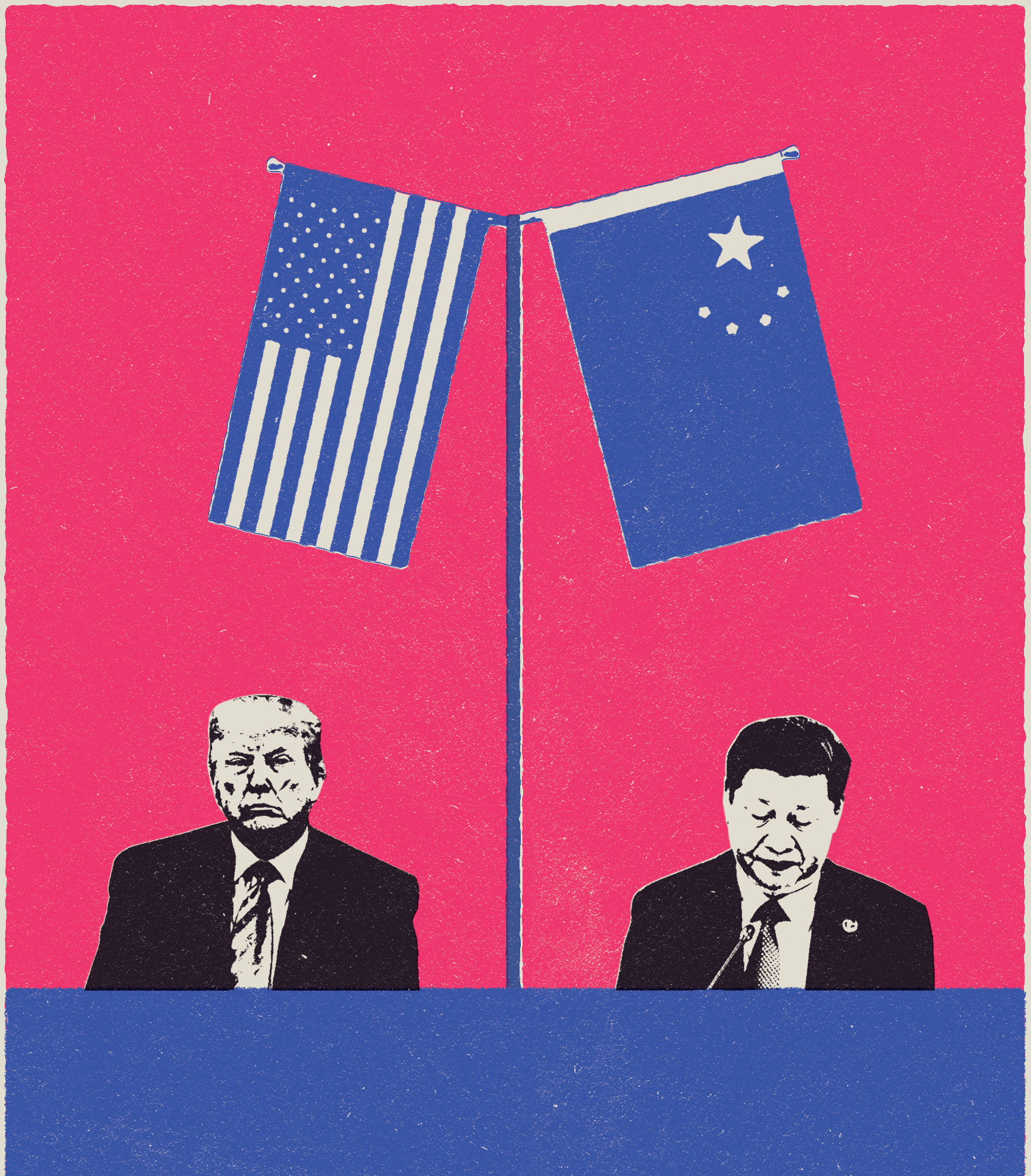

In just a few years, however, those deals have been reopened, or rejected outright. With populism gaining traction, the very concept of free trade as a net good is increasingly questioned by leaders in the U.S., U.K., and some Asian nations as well. At the height of the 2019 trade dispute between China and the U.S., Cutler sat down with Asia Society Executive Vice President Tom Nagorski to talk about the past, present, and future of global trade.

Tom Nagorski: In your long career as a trade negotiator, you have worked on no fewer than 10 major trade deals. They are long, grueling, 24/7 endeavors. Is there some great backstory to how you became a trade negotiator in the first place?

Wendy Cutler: Trade is an issue that has always been of interest to me. It’s something I studied in college, and it seemed like a vehicle that helped take a lot of people out of poverty around the world. When I started appreciating the international benefits of trade, as well as what it meant for the U.S., I became increasingly passionate about it. I entered the government at the Department of Commerce and was thrust into trade negotiations at a young age, put at the table representing the U.S. within a few years of when I joined the Office of the U.S. Trade Representative. And once I could actually sit in that seat, representing the U.S. — at that time on the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT) in Geneva — there was no holding me back. This is what I wanted to do.

Is it fair to say you also came into that role at a time when this notion of fair trade as an unalloyed good for the U.S. and the world was at a high point? We’re talking early 1990s, mid-1990s; there was not a whole lot of questioning, at least in this country, that it was good to have a U.S. trade representative; it was good to pursue these deals.

Well, absolutely. And when I look back at the early part of my career, I wish I had valued all the support we were getting at that point because people weren’t questioning the benefits of trade. The labor movement still had concerns and we took those concerns seriously, but for example, there was strong bipartisan support from Congress. It wasn’t a matter of whether we should be going forward with these deals but more of how we could make them not only beneficial for the United States but also for our trading partners.

magazine text block

Now that whole notion — that free trade between nations is fundamentally a good thing for humanity — seems to be under attack, certainly in many quarters of this country and in other parts of the world. The U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement and the TPP were big landmark deals with Asia front and center. Then President Trump comes to office and the Trump administration very quickly says these are bad deals, and pulls out. What’s it like, given all the blood, sweat, and tears put into it? What’s it like just on a personal level to see these things gutted so quickly?

On a personal level, obviously it’s very difficult to watch any project you’ve worked on for many, many years to be basically eliminated with the sign of a pen. But more importantly, with respect to threats to withdraw from the U.S.-Korea FTA and also the actual withdrawal from the TPP, I felt that as a country we were going to lose.

I feel somewhat vindicated on both fronts because I don’t think anyone really understands how difficult a trade negotiation is until they’re the ones at the table. When you’re not at the table, it’s easy to say: “We needed a better deal. Our negotiators were incompetent. If I were at the table, I could achieve this.” And I think this administration, like previous ones, has learned that these talks are hard and the results that you’re able to achieve — assuming you’re able to reach closure in the negotiations — are going to require a give and take.

With the U.S.-Korea Free Trade Agreement, the president ended up not withdrawing but rather amending it. When I look at those amendments, they were modest and — frankly — things that I think any previous president probably would have asked for had the agreement continued over the years.

And with respect to the TPP, somewhere between 50 and 75% of the new NAFTA actually includes language straight out of the TPP. So, in many respects, whether it be digital trade, or state-owned enterprises, the environment, or labor, the new NAFTA’s rules are very close to the TPP. In certain areas they built on the TPP, they improved it; and in certain other areas they took away some of the TPP benefits and came up with new ways to address these issues. But overall there are a lot of similarities.

magazine quote block

magazine text block

Whether you’re pro-free trade or not, it’s fair to say some of this stuff can seem, certainly to the layperson like myself, pretty arcane. Some of the issues that you spent all that time working on are not that easy to understand. Let me ask you to give the general public some examples of what really matters to them. How does trade impact the consumer, the business owner, et cetera?

Trade brings enormous benefits to our overall economy but also to families, communities, and individuals. You mentioned consumers, for example. As a result of trade, we’ve seen lower prices and more choice. We now can buy vegetables year-round because many of them are imported in the seasons when we don’t produce them. And, obviously, when tariffs are imposed and additional ones are being threatened, the consumer is going to see prices increase.

Keep in mind that a lot of trade is not only about imports that benefit consumers, but it’s also about exports. The United States is a very innovative, productive country. We export loads and loads of agricultural products, manufacturing products, services, ideas, and intellectual property. All of those exports have to go somewhere. When you produce those exports, you’re employing people in the United States. And what the statistics show is not only do exports create thousands of jobs per a billion dollars worth of exports, but most of these jobs are higher-paying jobs than jobs associated with the traditional economy.

Through the years, trade has helped lift people out of poverty and also contributed to economic growth and to the promotion of innovation in economies around the world.

Now, that said, I’ll be the first to admit that there are people who do not benefit from trade. And I think that the United States needs to do a much better job taking care of those people and also promote policies that get our workforce ready for the international marketplace of tomorrow.

Given all the prosperity that’s been realized through trade with Asia, what happened? Why is free trade as a concept, as a doctrine, not just under some review and debate but really fallen into disfavor?

Well, it’s an interesting question. Institutions like the GATT were established right after World War II. Let’s remember the United States was by far the number one economic power at the time, and our objective was to help other countries recover in the aftermath of the war and help them grow their economies. And what’s a better way to grow your economy than to open up our markets and work to open their markets so we could trade? The idea was that this was going to be a win-win proposition, not only for the United States but for other countries.

magazine text block

And for a while it was, right?

Absolutely. But what has happened is that people are questioning the benefits of trade now because the United States is not the only game in town. What we’ve seen over time is many other countries — whether it was Japan 20, 30 years ago or China now — threatening our supremacy in the trade area. There is a feeling that these countries have not had to live up to and adhere to the same obligations that the United States lived up to under the GATT and the WTO. And as a result, the feeling is that these trade agreements have exacerbated income inequality in countries like the U.S., in Europe, and I think we’re going to see this emerge in other advanced, developed countries. The feeling is that now a lot of the countries that were once on top of the world are really being disadvantaged by trade.

Let’s get to the heart of the issue in the trade war that the United States and China are waging, which dates in its current form to the new administration in Washington. It all started because the United States said China is not playing fair — whether we’re talking about trade or currency issues or other things. How did this start?

First, it didn’t really start with Trump. There was frustration building up with respect to China for many years and most acutely during the second term of the Obama administration.

There is just a fundamental view that there’s not a level playing field between the United States and China when we’re trying to trade and compete in the world on the economic front. For example, China does not adequately protect and enforce intellectual property rights — an area where the United States is extremely competitive. China provides its companies with financial assistance, both direct and indirect, which provides advantages that are not enjoyed by private companies around the world.

When it comes to technology in particular, China is focused on subsidizing the next generation of technologies at the same time that it’s forcing our companies to turn over their knowhow, their source codes, their intellectual property, their trade secrets, as a cost of doing business in China. If you put it all together this is unfair. This was never contemplated. This wasn’t the pact that we expected with China. There’s a growing feeling that the past approaches of trying to work with China, attack these practices, and address them to the World Trade Organization — we’re making some marginal improvements, but overall are not fixing the situation. So a new approach was called for and that’s where our president has been extremely vocal and focused on.

magazine text block

And, just to be clear, you have no issue with the fact that you felt some stronger measures or some standing up to China in this regard was appropriate.

That’s correct. I agree that the time had come to call China out and to try and find a new way to get Beijing to play fairly.

But I also think you’re not a big fan of what seems to be this almost never-ending cycle of the threat of a new tariff, a tariff being implemented, maybe some talks in Beijing or Washington, and then those talks collapse and we have more threats and more tariffs. We’re in the middle of a cycle like that right now. Tariffs are the antithesis of free trade. What do you think about the tactics that have been used to carry out the standing up to China?

Well, to share a story with you: I worked for nine U.S. trade representatives throughout my career and a number of them through the years would ask us, “Why don’t we just impose tariffs against this country if it’s not playing by the rules?”

Our response was basically twofold. Number one, we would break our obligations under the World Trade Organization which would then invite other countries to do the same — and that would work against our interests. And, two, tariffs end up hurting the United States, whether it be our consumers, our workers, our farmers, or our businesses. Frankly, both of these concerns have really played out in real time.

Perhaps it was worth it to go ahead with the first tranche of tariffs against China. It clearly got their attention. It got China to the negotiating table. But, I don’t think they’ve played out the way that the Trump administration expected.

There was hope that once we started imposing tariffs China would be hurting economically, cave, and come to the negotiating table and make major concessions. And unfortunately what we’re seeing is that the Chinese are not only responding by counter-retaliating, but their position seems to be hardening. They seem to be saying: “We’re not going to respond to these tactics. We’re not going to cave. We have the wherewithal to get through this tit-for-tat tariff dispute.”

Right. And I believe on many occasions the president himself, or others in the administration carrying out these policies, have said: “First of all, it’s not going to hurt Americans — at least not as much as it’s going to hurt the Chinese.” And there’s been an implication that it’s going to bring more manufacturing jobs back to the United States. What’s okay or not okay with those arguments?

Let me be the first to admit that the tariffs are hurting China. We’ve seen their manufacturing output going down. We’ve seen some plants being closed. We’ve seen economic growth decline over previous quarters. But what we’re also seeing is that the United States is suffering from these tariffs as well. And particularly as more and more products are hit by U.S. tariffs, and China responds with counter retaliation, the hurt to U.S. consumers, workers, farmers, and businesses is now becoming more and more acute.

magazine text block

So just marrying the current conversation with the U.S. and China with this broader look at what’s happened to the doctrine of free trade. Does the fate of the U.S.-China trade war, as we’re calling it now, have the potential to really steer the world in a different direction?

There’s one scenario where this just goes down the tubes and then it’s really protectionism writ large between the two largest economies on Earth.

Or, if a deal gets done, might you see a way in which people do start to see the benefits and maybe we’re back to a place where free trade as a policy and as a proposition suddenly comes into better regard, its reputation might be salvaged if things go well?

I don’t think we’re ever going to get back to where we were. I believe we are in a new world and we need to be more cognizant and responsive to concerns about trade that have been expressed by many constituencies in the United States.

With respect to China, we’re at a juncture in these negotiations where it’s uncertain where they’re going to lead. If they lead to a deal, it’s not going to be a perfect deal. But I would expect we’ll have a deal that would make sufficient progress to allow both sides to lift some of their tariffs at a minimum. And maybe to get back to some new normal — to be defined.

If you had the possibility of a few moments in the Oval Office sometime soon — let’s say tomorrow you’ve got 15, 20 minutes with the president — how would you make your case given all the things you’ve thought about and been talking about here? What would you say to Trump?

The United States has a strong and innovative economy — in order for us to continue to grow and to create the kind of jobs that we need, we need to export, we need to be part of the international trading system.

At the same time, we need to address the concerns of those who are left behind: through some social safety net policies, and also by educating the next generation of workers to make sure that they are ready and prepared for the new types of jobs that are going to be created by the new technologies that are that are now hitting the streets.