magazine text block

A Collapse in Afghanistan Restores The Taliban to Power

When President Joe Biden announced in April that the U.S. would withdraw the remaining 3,500 troops from Afghanistan by late summer, experts largely agreed that, eventually, the Afghan government would fall to the Taliban. Even still, no one was prepared for it to happen so fast. On August 15, six weeks after the U.S. military left Bagram Air Base, Taliban fighters entered Kabul and assumed control of Afghanistan for the first time since 2001. The U.S. then spent the next two weeks in a furious scramble to evacuate as many Americans — and Afghans who had helped the U.S. effort — as possible. Hundreds of thousands were brought out of the country, but in the midst of the evacuations a terrorist attack killed 13 U.S. service members and dozens more Afghans. On August 30, nearly 20 years after U.S. troops entered Afghanistan in the wake of the September 11 attacks, the last American soldier departed the country.

The chaotic withdrawal sparked fierce criticism both within the United States and among America’s allies across the world. But the consequences for Afghanistan are far graver. While the U.S. failed to build a self-sustaining Afghan government, the two decades of occupation had brought significant change in the country. A generation of Afghan girls attended school and entered the workforce. Telecommunications and media flourished. Kabul and other cities leapfrogged into modernity, their upwardly mobile residents better connected to the outside world than ever. But for Afghans living in the vast hinterland, the two decades of U.S. occupation left behind a different legacy — one characterized by little progress amid constant internecine violence.

Upon taking power, the Taliban initially struck a conciliatory tone, promising that they’d evolved from the group whose draconian rule had elicited international condemnation in the 1990s. Their new leaders swore that they would not harbor terrorist groups, and that they would be more supportive of women’s rights and other freedoms. But early indications have not been promising. Thousands of Afghans who’d risked their lives for the United States and its allies over the previous two decades remain inside the country, fearful of reprisals from Taliban fighters. Women, once again, are barred from attending university.

Sorting out the geopolitical implications of the Taliban’s return may take years, as numerous players — the U.S., China, India, and Pakistan among them — adjust to the new status quo. But in the early months of “Taliban 2.0,” a more basic question emerges: Is anyone capable of uniting this fractious country of 38 million people — more than 65% of whom were born after 9/11? There are few reasons for optimism.

“The current situation is simply unsustainable,” Tamim Asey, a former Afghan government official, said during an Asia Society Northern California town hall event in October. “It’s sowing the seeds for a full-blown war.”

Outside the mortuary of a COVID-19 hospital in Ahmedabad, India, a woman mourns after her husband dies from the disease on May 8, 2021.

Amit Dave/Alamy

magazine quote block

magazine text block

COVID Explodes Across Asia

Throughout 2020, as COVID-19 devastated North America and Europe, much of Asia (China aside) remained largely unscathed, leading to claims that the world’s most populous region had, somehow, discovered a formula for avoiding the calamitous pandemic. Asian countries were generally slow to procure sufficient vaccines once they became available in late 2020, believing that inoculation was less urgent due to their successful suppression of the virus.

Asia’s good fortune did not hold in 2021. Across the continent, country after country experienced larger and more frequent viral outbreaks than they had the year before. In India, a terrifying spring surge, fueled by the hyper-infectious “delta” variant, claimed hundreds of thousands of lives in a matter of months and exposed deficiencies in the Indian government’s response. “The state’s relationship with science has been tenuous at best throughout this pandemic,” Dr. Satchit Balsari, a professor at Harvard Medical School, said in an Asia Society India program in May. “They’ve tried to minimize COVID deaths, as if it’s some bizarre badge of honor in the middle of the pandemic.” The outbreak was so bad that India halted exports of vital vaccine doses to the rest of the world, a major setback in the global effort to stop the spread.

Countries elsewhere on the continent experienced similar travails. In Indonesia, hospitals ran out of oxygen as doctors, even those who were fully vaccinated, perished in alarming numbers. COVID breakouts in South Korea and Japan were worse than what either country experienced in 2020. Even countries that had claimed to have largely suppressed COVID-19, like Australia and New Zealand, abandoned a “zero tolerance” strategy in an acknowledgement that they would have to live with the virus.

By year’s end, the pace of vaccinations had quickened across Asia, even in poorer countries, sparking hope that 2022 might bring better news. And, all things considered, most Asian countries have still managed the pandemic more ably than the United States and Europe. But delta’s rampage across the continent in 2021 disrupted a triumphant narrative that had taken hold in 2020: that Asia had, by and large, dodged the pandemic’s bullet.

A protester shouts slogans during a demonstration against the Myanmar military coup in Mandalay on February 28, 2021.

Alamy

magazine text block

A Coup Overtakes Myanmar’s Fragile Democracy

On February 1, Myanmar’s military announced that it had dissolved the country’s civilian leadership, detained de facto leader Aung San Suu Kyi and other figures in her National League for Democracy (NLD) party, and assumed power in a military coup, halting the fragile, decade-long democratic transition.

The ostensible reason for the coup was the result of nationwide elections held in November 2020, in which the military fared poorly and Aung San Suu Kyi’s party captured the vast majority of seats in parliament. “The military felt quite threatened because the NLD had won a huge mandate,” Scot Marciel, former U.S. ambassador to Myanmar, said in an Asia Society program held soon after the coup. “It was a pure power grab.”

In the ensuing months, the military violently suppressed pro-democracy protests across the country, and reneged on a promise to return Myanmar to civilian rule by February 2022. This political turmoil exacerbated long-simmering ethnic conflicts and stymied efforts to manage the spread of COVID-19. Economic conditions in an already-poor nation have deteriorated: The World Bank projects that Myanmar’s economy will contract by 18% in the 2021 fiscal year. As of this writing, the future of Aung San Suu Kyi’s leadership, as she is now 76 and once again in custody, remains in doubt; the fate of her country currently seems little brighter.

Israeli demonstrators celebrate the passing of a vote confirming a new coalition government during a rally in front of the Knesset on June 13, 2021 in Jerusalem, Israel.

Eddie Gerald/Alamy

magazine text block

Elections Upend Politics in Israel and Iran

In the middle of June, two of West Asia’s most powerful countries — Israel and Iran — held consequential elections a mere six days apart. On June 12, an unwieldy eight-party coalition prevailed in Israel’s national elections, elevating Naftali Bennett to prime minister and unseating the powerful Benjamin Netanyahu after 11 years in office. On the 18th, Iranian voters chose Ebrahim Raisi, a hardline cleric, as their new president in an election marred by numerous disqualified candidates and a distinct lack of voter enthusiasm.

“Iranian elections have always had a unique combination of being unfree, unfair, and unpredictable,” Karim Sadjadpour, an Iran expert at Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, said during an Asia Society New York program in July. “This election was unfree, unfair — but predictable.”

Neither of the new leaders appear to augur a significant policy shift for their countries. Bennett, the head of Israel’s New Right coalition, seems poised to continue his predecessor’s uncompromising stance toward the country’s Palestinian population. As for Raisi — thought to be an eventual replacement for Iran’s supreme leader, Ayatollah Khamenei — early evidence suggests that he will not easily yield to U.S. demands in negotiations over Iran’s nuclear program. Policy stakes aside, the elections nonetheless each had symbolic significance. For Israel, Bennett’s victory punctured the aura of invincibility that Netanyahu had enjoyed for years — even if the long-serving prime minister’s ideology largely remains in place. Raisi’s victory in Iran, meanwhile, removed any lingering doubt that the country’s theocratic leadership would remain unchallenged.

A woman walks past an Alibaba sign outside the company's office in Beijing on April 13, 2021.

Greg Baker/AFP via Getty Images

magazine text block

China Cracks Down on the Private Sector

The conflict between the Chinese government and the private sector, which began with the suspension of the financial behemoth Ant Group’s initial public offering in 2020, accelerated in 2021. In April, China’s market regulator imposed a $3 billion fine on Ant Group’s parent company, Alibaba, for “monopolistic behavior,” while in July cyber-regulators demanded that Didi, China’s Uber, be removed from app stores pending an investigation into the company’s compliance with data laws. That month, Beijing also effectively killed China’s multi-billion-dollar for-profit education sector by announcing that firms, overnight, reorganize into nonprofits.

China’s actions against some of its best-known companies has had a profound economic effect: Between February and August, $1.1 trillion was knocked off the combined market value of China’s top six technology stocks alone. But the real legacy of this crackdown may be political.

“The best way to summarize it is that [Chinese President] Xi Jinping has decided that, in the overall balance between the roles of the state and the market in China, it is in the interests of the Party to pivot toward the state,” said Asia Society President and CEO Kevin Rudd in a September 2021 speech. “In doing so, it reflects Xi Jinping’s wider worldview on the role of the Party, the state, and the market in the transformation of modern China into a global great power — one in which the Chinese Communist Party nonetheless retains complete control.”

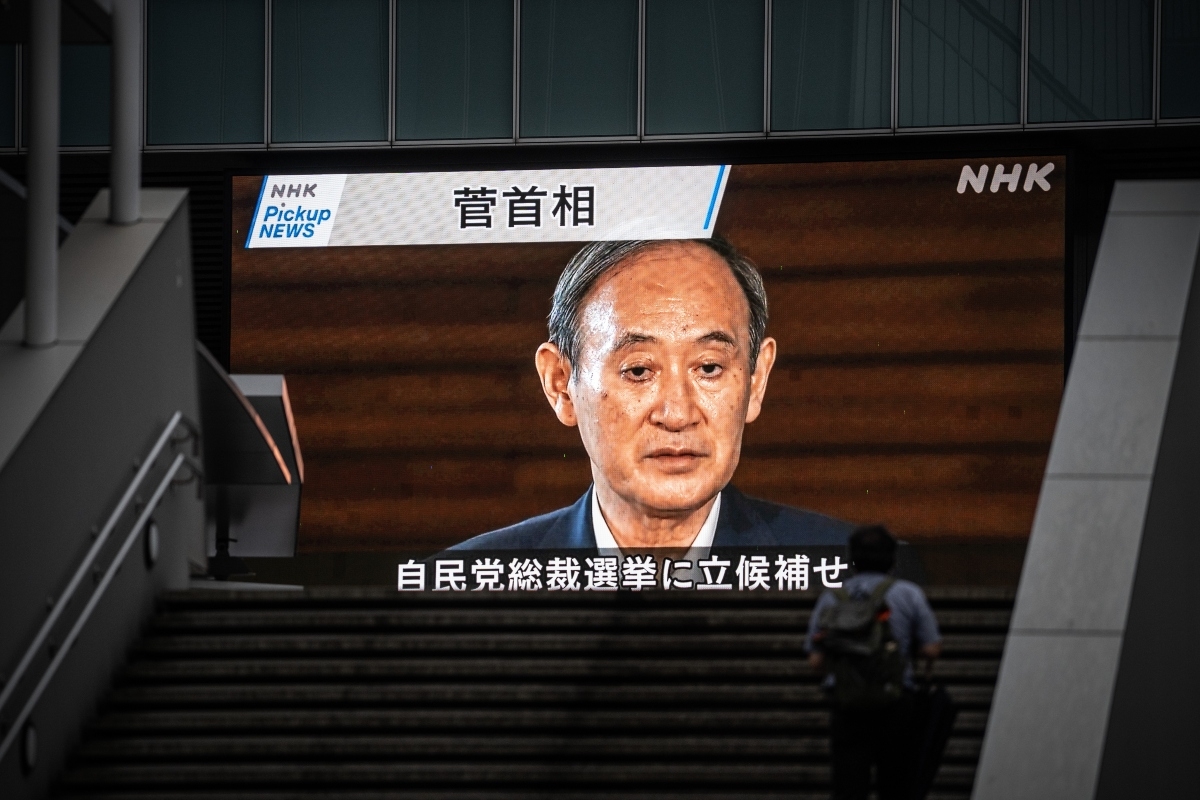

A giant screen shows a news report detailing the announcement by Japan's Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga that he will not stand for re-election at the forthcoming Liberal Democrat Party leadership contest, on September 3, 2021 in Tokyo, Japan.

Carl Court/Getty Images

magazine text block

The Pandemic and an Unpopular Olympic Games Cause a Japanese Prime Minister To Resign

When then-Prime Minister Shinzo Abe popped out of a Super Mario Brothers’ costume at the closing ceremonies of the 2016 Olympic Games in Rio De Janeiro, initiating the symbolic transition to the Tokyo 2020 games, Japan had every reason to be excited about hosting the quadrennial sporting competition: A successful Olympics would signal that the country had fully recovered from 2011’s earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear disaster at Fukushima.

Neither Prime Minister Abe nor his constituents could have imagined what 2020 would bring.

The emergence of COVID-19 initially forced Japan to postpone the Games, originally scheduled for July and August 2020, by one year. By the spring of 2021, with COVID still raging and vaccinations slow to transpire, most Japanese people seemed to think that the Olympics should be scrapped entirely. An April poll found that nearly 80% of the population opposed the Games going forward that summer. Instead, the Japanese government and the International Olympic Committee forged a compromise, allowing the world’s best athletes to compete but barring spectators from watching.

From an athletic point of view, the resulting games were a success. But the spectacle was less joyful for Tokyo’s population, who were forced to endure strict COVID-19 lockdowns and were unable to capitalize on the expected tourist bonanza. For Prime Minister Yoshihide Suga, who insisted that the Games proceed, his tenure in office barely outlasted them. He announced on September 2 that he would not seek re-election.

Rescuers help evacuate stranded people at the entry to an expressway in Zhengzhou, a city in central China's flood-ravaged Henan Province, on July 23, 2021.

Xinhua/Alamy

magazine text block

Terrifying Floods in China Punctuate a Year of Climate Disaster in Asia

As viral videos go, few were more terrifying than those filmed in Zhengzhou, China, in July: As historic rains flooded the city’s subway system, terrified passengers trapped in a car hoisted themselves up to avoid being submerged by water that had reached shoulder height. The flooding in the subway system ultimately killed 14 and temporarily displaced more than a million others; in the end, more than 300 people in and around Zhengzhou lost their lives to a storm in which an astonishing eight inches of rain fell in the span of one hour.

Zhengzhou’s flood disaster was only the most high-profile extreme weather event in a year, like recent years preceding it, when such events became almost common. A tropical cyclone that struck Indonesia in April killed 160 and displaced 22,000 others. In West Asia in June, summer temperatures soared over 120 degrees across a wide swathe of the region, setting records in multiple countries.

In September, President Xi Jinping announced that China would cease building coal-fired plants abroad, a move that triggered widespread praise. But at year’s end, China’s own coal production was still booming, and the flooding in Zhengzhou — where the submerged subway line opened only two years ago — illustrated the speed at which climate change is reshaping our world.