'West of Kabul, East of New York' with Tamim Ansary

The day after the terrorist attacks of September 11, Tamim Ansary, a children's book writer and columnist for Encarta, wrote an anguished email to a few of his closest friends, explaining how the situation looked from his perspective as an Afghan American. "We now come to the question of bombing Afghanistan back to the Stone Age," he wrote. "Trouble is, that's been done." Within days, his September 12 email had been forwarded to millions of people all over the world, and Ansary became the unofficial voice for the Afghan people.

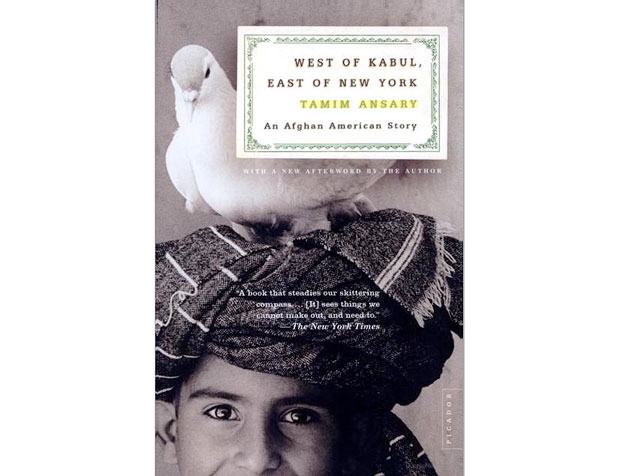

Tamim Ansary was born in 1948 in Kabul; his father was an Afghan, his mother an American. His first 16 years were spent in prewar Afghanistan, where he was raised in a close-knit extended family. Ansary left Afghanistan in 1964, along with his mother and siblings, to study in America. But it turned out to be only the beginning of a life spent at the crossroads between the traditional Islamic society of his youth and the secular Western culture he came to call his home. Asia Society spoke with Tamim Ansary about his recent memoir, West of Kabul, East of New York: An Afghan American Story, and how his life as an Afghan American was transformed by September 11.

It seems that your life, like many, has been turned upside down by September 11. Did you plan to write this book before September 11? In what ways have your plans changed since your September 12 email?

I did plan to write this book before September 11, and I had written certain portions of it over the course of the last couple of years. I wanted to address a central preoccupation of my life that I thought would be interesting to other people as well: my bicultural identity, and the question of the differences, conflicts, and possible reconciliation between these two cultures. It certainly was interesting to me, even before September 11. That's something that expressed itself in my life just through an accident of history, and so I was always planning to write about that.

However, it's true that the conception of the work changed after September 11 because my own focus, and the focus of everybody's conversation and thoughts, was so much about the question of terrorism as it related to East and West. And so, out of that larger work I had been planning, it came to me to carve out the smaller work that was more tightly focused on the issue that I'm talking about in the book.

You've been asked if you regretted anything you said in your September 12 email, considering you never intended it be read by so many people. I am curious about what more you would have said if you had known your email would reach, and find resonance with, such a wide audience. Does this book address some of the things you might have said?

There continue to be more things I want to say, beyond the email, that have emerged as time goes on, and that I have been talking about. Wherever I go and read from this book, people ask questions and new things come up. In that sense, my thoughts keep enlarging and unfolding. But this book is actually not an extension of the email, because the email was a polemic, and this book is a memoir. It's in a sense much gentler. I think of it as storytelling, rather than analysis, that revolves around the times in my life that involve loss, or love, or adventure, or dealing with change, or growing up, or death.

Someone asked me the question, "Do your kids know all that you've been through?" And I wanted to say, "No, it's not that I've been through that much. I wasn't in Afghanistan; those guys went through horrific things. My life has not been that adventurous but fairly quiet." When I talk about things like culture separating me from my father, and what it was like for him to die so far away and me not to have seen him for 16 years, I'm only talking about the particular way that loss manifested itself in my life. I feel like we all have versions of these peaks and lulls and high points and losses. So in that sense I'm not saying, "Oh look at me, because I've had an experience that's unlike anybody else's." I think my life is, in a lot of ways, like everybody else's, but it's just got these particular characteristics.

You describe your September 12 email as a time when you "spoke for Afghanistan with my American voice." But due to the volatility of the period immediately after September 11, and also due to the immediacy of the Internet, your email addressed a very specific moment in time that has now passed. What was a clearly stated analysis of a situation in Afghanistan that few Americans knew about now reads as common knowledge. Do you see this book as an extension of this "American voice speaking for Afghanistan" from your email?

To some extent that certainly is true. In the whole first part of the book where I describe my childhood in Afghanistan, I'm speaking in my American voice about not just my Afghan self, but also the context that gave rise to that Afghan self. I feel that the culture of Afghanistan in those days before the war was something that nobody had been situated to describe in a way that could make Americans really see it. One reason was, those who experienced it didn't speak English, and beyond that, even those who did experience it, while being very literate like my father, had literary impulses that expressed themselves through poems that were epic or lyric but not through a descriptive evocation of a time and a place.

I think I am using whatever voice I have to speak for not just Afghanistan, but also for a certain kind of cultural and social coherence that has passed away in a lot of places, especially in the parts of the world we now describe as the developing world. I think it is only recently that secular Western civilization, thoroughly industrialized and technology-driven, has come in contact with cultural frameworks that are much more traditional and more ancient. I was using what voice I had to describe that older culture and what it was like to experience it, and maybe to try to evoke what was lost.

But having written this book, I discovered two things are true: Afghans who talk to me say, "Oh yeah, that's really how it was. You got it." They like what I said and they like me for having said it. So I'm discovering to my own delight that I did speak for Afghans in that way. And then I have also heard from many Americans who have read the book that they are very interested in this portrait and that it shows them and tells them something about Afghans and Afghanistan they find likable. Then I think, "Wow, I did speak for Afghans." So surprisingly enough to myself, the answer is yes.

Despite America's strong desire and need to learn more about Afghanistan's history and culture, we have heard from relatively few Afghan writers. How do you think other Afghans will be able to start to speak for themselves?

I think you're going to see that coming. One of the reasons I say that is because now that I've published a book and I've been reading from it, I've been meeting lots of Afghans who are interested in writing and who are writing here in America.

Afghans came here relatively recently; most of them came 20 years ago or less, and most of these people spent maybe the first 10 years just trying to figure out how to survive. Now, for the first time in the last couple of years, there are Afghans who are articulate in their second tongue, or they're young Afghans for whom English has become their first language. There is a large enough pool of such people that sophisticated writing can begin to emerge.

Just the other day I was reading at the Society for Afghan Professionals in Fremont, California, and I met a man who wanted to interview me for the Afghan Internet site Lemar - Aftaab. Of course, he had also written a short story and asked what I thought. I read it, and it was pretty moving to me. I thought it was really well done; I liked it a lot.

I also met a young doctor named Khaled Hosseini who is writing a novel about Afghanistan that I am actually jealous of. I immediately thought, "Wait a minute, I was going to write that!" So there's Afghan writing coming, for sure.

A review of your book says that it can be seen as "illustrative rather than revelatory, reinforcing what we feel we understand rather than shedding new light or bringing new understanding." What do you think is the role of memory, and of the memoir, during such times of political and cultural upheaval?

The role of memoir and of memory in general is something that I think is very important. It's my view that you find the meaning of your life in the arc that unfolds as you live. I am very interested in pushing this view here in America, because I think the opposite point of view has a great hold on the American imagination, which is that the past doesn't matter--you don't need to think about it; just start from here and go towards tomorrow. My view is so strongly that there is no "right here" without the past, and that remembering and finding the patterns and meaning of the past is very much not the same thing as living in the past. It's an attempt to find the meaningful pattern in what you're doing and where you are going.

And in the same way that that's true of a personal life, I think that's true of our cultural life. It's all very good to have official histories and dry texts taught by Harvard professors about the unfolding history of our times, but I think memoirs are the lifeblood of history. It's important to keep remembering that history, seen up close, is nothing but myriad memoirs interlocking and intertwining. So I'm adding my little bit to that tapestry.

The difficulties you describe in growing up bicultural are resolved differently by each of the Ansary children. Your younger brother embraces an orthodox interpretation of Islam, while your older sister settles into a wholly secular American life. You, the middle child, try to "straddle the crack in the earth" between both cultures, although, as a non-practicing Muslim, you remain more firmly on the American/ Western side. Do you think that your siblings' struggles to reconcile themselves with the differences between both Islamic and Western ways of life mirror the struggles many Muslims feel about this issue?

Definitely. I think that the Islamic world has been going through a period of self-examination for at least a century or more that has to do with its encounter with the West, in a way that the West hasn't been doing because of its encounter with Islam. I would say that most of the West as an overall entity has been almost unaware of Islam. It has overwhelmed Islamic civilization and barely noticed it was there. But Islamic civilization is very much aware of the West, and has been asking for these several centuries, "Wait a minute, what's going on here? We're the world's civilization, what are we doing wrong? No, it can't be our fundamental premises that are wrong, so what is it?"

They've been going through this, and there have been movements arising in Islam that at some times said, "Okay, we can be Muslims, but we have to accept technology." And then other movements have said, "The problem is all the new social ideas, let's smash those and get rid of them." I think that going back and forth and trying to figure out a stance is certainly a part of what's been going on in the Muslim world and also of what has ended up generating these troublesome sects.

You write in your book of the difficulty in growing up between Islamic and Western lifestyles; "When you're in two worlds so different, your mind is forced to say that one is legitimate and the other is a crock." Do you think it is possible to live in both cultures in a way that is simultaneously acceptable to both, without necessarily declaring one "a crock"?

I think that is a difficult question. I want to say, "Yes, of course"; I don't want to say it isn't possible. I think where I come down is that in terms of the world, it is important for the West to be able to somehow step back and let go, and let societies whose overall impulse is to discover their own way become Islamic societies. We in the West have to allow some societies to be Islamic if they want to be, and many do want to be. And what that would mean in some places, possibly in Afghanistan, is that they wouldn't be pluralistic and kaleidoscopic societies, because I think there is something in the vision of Islam that demands that a society have a certain uniform pattern; Islam is not solely about personal conduct.

It's a different question when you come to Muslims living in America, however. America has its own vision, one that I subscribe to, and if a Muslim comes here, they have to find a way to satisfy their religious life and also become part of America's pluralistic, multicultural society, with tolerance for all others and without demanding anything of the society that's special for Muslims. I think they have to be able to accept that you might go to a restaurant and the guy at the next table might be eating pork while the guy at the table after that might be drinking martinis. I think the two systems ought to be able to coexist in the world, and there also has to be a way for purely Islamic societies to exist in the world.

A reviewer wrote that your book was "highly useful for anyone seeking to understand the Muslim world's hatred for the West." It could be said, however, that your book could be more useful in helping the West understand the peaceful and benevolent Islam of your youth, before the growth of extremist Islam in Afghanistan and other Islamic countries. What understanding of Islam did you hope to bring with your book?

I think I wanted to bring both, because I see that there are two angles to this. I think that in portraying the peaceful Muslim society of my youth, I did want to bring this vision of Islam to Americans and show that this is how a lot of Muslims live and want to live. At the same time, I became aware that there was an emerging political ideology in the world that had its roots in Islam. That is to say, it was finding in the myths and narratives of Islam a way to justify and to rally people for a political purpose. Because this political ideology has been emerging in the Islamic world, I think it's important to see the people that are behind it and how they're managing to construct such effective propaganda. It's important because, in my view, we are actually in competition with that Islamist, extremist point of view. And the competition is for the minds and hearts and allegiance of most of the Muslim world.

I would say we're not at war or in conflict with the Muslim world; it's not a done deal whatsoever. I would not even say of fundamentalists that they are our enemies. Because when you speak purely of religious fundamentalism, of somebody who wants to pray five times a day and live exactly as the Prophet Muhammad and not wear western clothes and so on--well, so what? Let them. Why would we have to go kill that guy? And we would be wrong to assume that someone who does all those things is a militant, much less a terrorist. But the militant and the terrorist are busy trying to convince the religious fundamentalist that you cannot do those things without being against Americans, because they're not going to let you do them. So we're in competition with somebody who is trying to tell millions of fundamentalists such a thing. Not to mention all the Muslims who are devout but not fundamentalist, or who are secular but not devout. I wanted to probably speak about both of these things in my book.

There is much discussion about the need for the return of the intellectual middle-class to Afghanistan during this time of rebuilding. Do you think that is what the country needs, and if so, do you have any plans to return?

I'm about to take a trip that's going to end up, I hope, in Afghanistan. I personally don't plan to go back to Afghanistan to live because my life is here in the West. However, since September 11, it has become clear that my life is very much involved with Afghanistan. This wasn't a one-shot deal. I think for the rest of my life I'll be heavily concerned with what happens in Afghanistan.

I know that lots of people who have been living in the West are talking of going back. And I think one of the things that I'm going to be interested in seeing for myself when I go there is how things are going between the people who stayed and the people who are coming back. I think it's an interesting dilemma that the country desperately needs the skills and the sophistication of those who have been living in the West, and yet, when they go back to try to contribute their skills (with very idealistic and warm impulses in all instances I've seen), they will instantly be the upper class because they'll be running things. And will the people who have been there all along be able to take orders from people who didn't suffer?

Right now, from all I've heard however, there's nothing but tenderness and warmth between those two groups. When I went to Pakistan two months ago to distribute aid in the refugee camps along the border, I was bringing blankets gathered by the American Friends Service Committee. That was my first visit back, and I felt that the people in the camps would very justifiably look at me with a certain hostility. They would say, "Wait, where were you all this time? We've been here in these camps, and yeah, now you bring some blankets, great." But it wasn't like that at all. Their attitude was, "You didn't even have to come back, you were in the States. And yet you came back; you didn't forget us. Oh, you're so good." It was a very heartwarming experience.

What is your next project? Where do you plan to go from here?

I don't know what my next project is. I have been thinking about writing a historical novel, which I might still go forward with, but I discovered that the exact episode in history I wanted to talk about has served as the basis for a historical novel published in the last four years. So I'm thinking well, maybe I have to think of something else to do. At this point I don't know. I think I'm just going to go and look at Afghanistan, and try to be involved a little bit. I'm also going to continue to do what I've done in the last six to seven months, which is bring information from that part of the world to this part of the world.

Interview conducted by Alexis Menten of Asia Society.