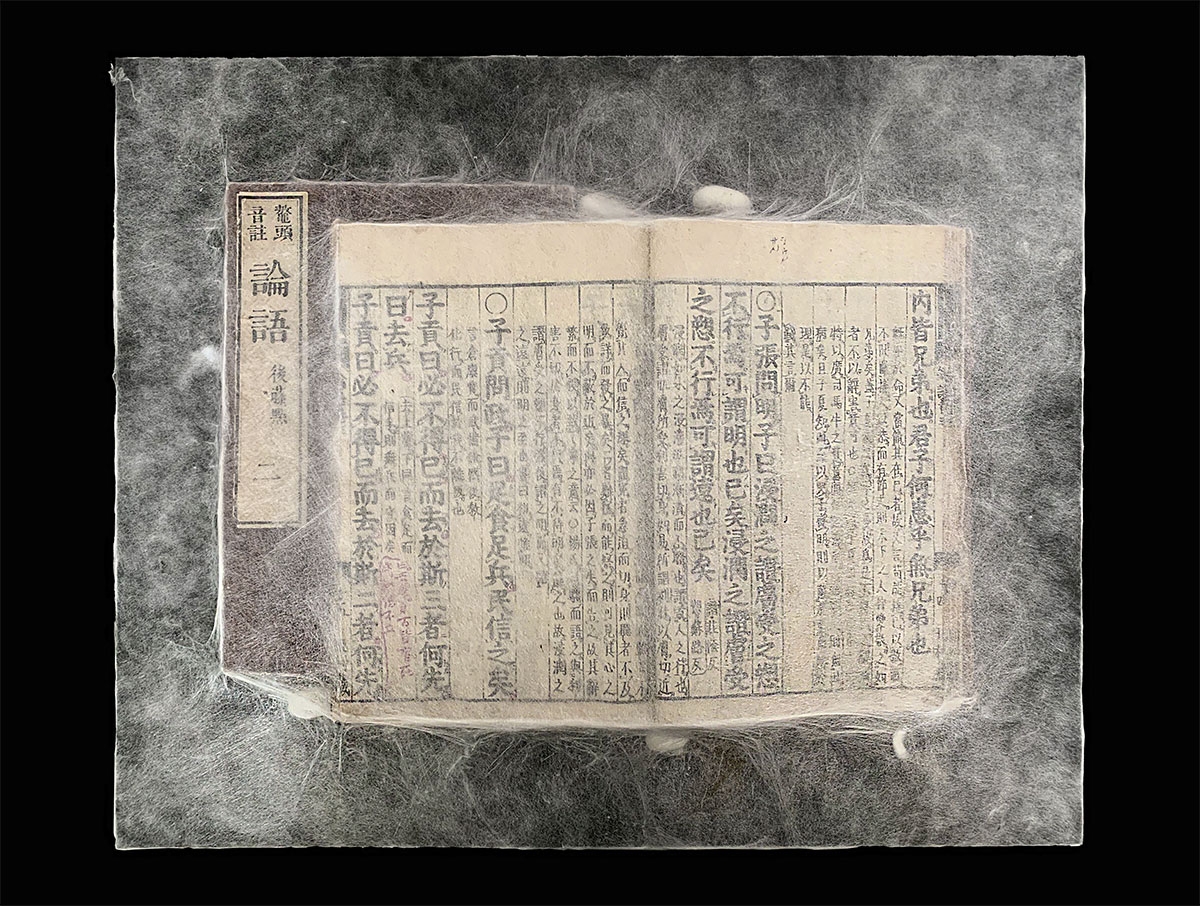

Photograph courtesy of Xu Bing Studio

-

Photograph courtesy of Xu Bing Studio

Dreaming With: Xu Bing

In the lead up to the Triennial opening, our Dreaming With Q&A series provides an exclusive glimpse into the artists’ lives and studios.

Where have you been during the lockdown?

During the lockdown, I was staying in my New York studio in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. I feel so grateful that I have a small backyard to breathe in some outdoor air.

Is there anything you have found yourself cooking a lot of, and if so, would you be open to sharing the recipe with our readers?

With the same seriousness as I used to make prints, I meticulously reject the virus from my territory. Never before have I spent so much time doing chores, cleaning the room, organizing the backyard that has long been neglected, and learning to cook. I am also in charge of sanitizing all the groceries.

What are you reading?

In great depth, I reread a lot of nineteenth-century classics by Victor Hugo, Nikolai Gogol, and [Romain Rolland’s] Jean-Christophe. Also Charlotte Brontë and Charles Dickens. At this age, the understanding of the same works turns out to be totally different from that of years before. The literature covers some of the most basic weaknesses of human beings, which are revived and exposed to another level during the COVID-19 pandemic.

What music are you listening to?

No, I rarely listen to music. Sometimes I enjoy the sound of nature and civilization from my backyard, instead. For example, the sound waves of the parade from the street in front of my studio. It is too blurry to comprehend the content due to the noise from the helicopter above my head and the sirens of the police car.

Have you seen any particularly good digital exhibitions in the past few months?

I cannot say I remember seeing any. Perhaps I am still not used to experiencing and judging art through the screen as a medium.

What do you find yourself working on most during quarantine?

I write a lot during the quarantine, recording in detail what I can feel and what I can lay my eyes on, despite the fact that I am confined to my studio. The keen observation of ordinary things can be surprisingly rewarding. I work remotely and use video conferences to collaborate with my studio staff from Beijing to discuss and proceed [with] ongoing projects.

How has your studio practice changed in recent months?

It came to me that my works from the past are neither personal nor emotional. However, my current practice is so personal and highly relevant to what has happened to my life during the pandemic.

What artists most inspire you?

Instead of artists and artworks, what inspires me the most actually comes from the ever-changing social scenes.

What are you most looking forward to about participating in the upcoming inaugural Asia Society Triennial and what do you most want viewers to take away from experiencing your work in the Triennial?

I hope that the inaugural Asia Society Triennial will not turn out to be so self-centered that it excludes those outside of the art world system, thus speaking to itself. After suffering from the pain of the pandemic and the dishonesty of the media and politics, people’s past understanding [of] their life and the world they are living in is no longer valid. [The] same thing applies to contemporary art. Please spare the audience the suffering from the drawback of contemporary art. The Triennial shall put the audience at ease and let them enjoy the connection between contemporary art and themselves.

Has your perspective as an artist changed in the midst of the pandemic and are there any fun facts about your practice you would like to share with readers?

The pandemic makes me reflect on why some art has values while other [art] does not. What are the differences? In my opinion, the art that has values resembles coronavirus in so many ways. If there is something called "contemporary art," it is like an "unknown virus" from outside of the body if we compare the human body to our civilization, lurking inside the biological system, grabbing the blind spot of the existing system, and breaking such a mature and complete system with something that was not available in the past. Its nature is unknown, its origin is undetected, and it has never been classified or categorized by any knowledge from the past. Then the balance is broken, it has to rely on philosophers, art historians, theorists, art critics, etc., to categorize and analyze these things (artworks), and, as a result, produce new knowledge. While these "unknown viruses" are being studied and understood, they are mutating into conventional viruses (such as influenza viruses) in order to adapt themselves to the environment; they turn into long-term service viruses and do the work of regulating and improving the body’s health at the right time. All are "viruses," the difference is "unknown" or "regular." A healthy body needs the attachment of some "bad" cells to cooperate with the “good” ones. As a group of “bad” cells, contemporary art is acting as a trigger point for the cleansing and reconstruction of human civilization through a seemingly naughty way.