Renewing the City: Efforts to Improve Life in Calcutta’s Urban Slums

By V. Ramaswamy

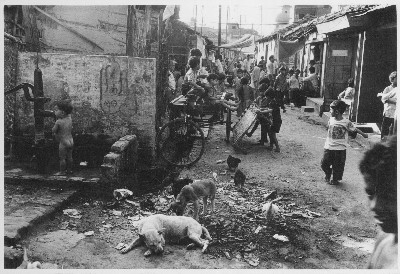

Metropolitan Calcutta is characterized by acute geographic, social and ethnic disparities. Such disparities severely threaten health, the urban environment and social harmony. A third of the metropolis’ population lives in deprivation from basic civic amenities in highly congested and degraded slums. These occupy large tracts of land in the metropolitan core. Simultaneously, uncontrolled urban sprawl to meet large-scale housing requirements endangers the ecologically sensitive wetlands fringing the city.

Metropolitan Calcutta, home to some 14 million people, sprawls over 1,350 sq km, spread in a linear north-south alignment along the east and west banks of the Hooghly river. (New York, for comparison has a population of 8 million in 800 square kilometers or 309 square miles), on the two sides of which lie the core cities of Calcutta (pop. about 5 million) and Howrah (pop. about 1.5 million).

Muslims constitute a bit under 20% of the population of Calcutta city. Over three fourths of the city's Muslim population may be living in slum neighbourhoods. There are likely to be deep-rooted and institutionalized attitudinal constraints to development in ethnic minority settlements. Socio-economic deprivation and disparity also breeds a criminalised polity and enhances sectarian strife.

Howrah, a million-plus, historically neglected city, is among the most blighted areas. Over half the population here lives in slums, a significant proportion belonging to the minority Muslim community. Available health and infant mortality statistics indicate high morbidity and mortality on account of waterborne diseases. Infant mortality rates in slums may be more than double those in non-slum areas. This stems from the continuing reliance of millions of vulnerable people living in the slum-like bastis (see below for a complete description) on contaminated water sources, in the absence of access to adequate supplies of potable water, and inadequate sanitation.

This forms the city context within which I have been working since 1984, when I joined the Chhinnamul Sramajibi Adhikar Samiti (Organisation for the Rights of Uprooted Laboring People), an umbrella-front of squatter communities in Calcutta struggling against demolitions and forced evictions. In 2001, I convened the establishment of the Metropolitan Assembly for Social Development, a civic platform to take up a concerted city-wide programme of slum community empowerment. This article seeks to elaborate on the problem situation, and the journey through civil society action interventions in pursuit of greater social and environmental justice in my city.

Bastis in Calcutta

Basti (meaning ‘settlement’ or ‘place of habitation’ in north Indian languages) in Calcutta has a culturally loaded connotation: the place where the city’s low-income and the poor, the laboring people, live. Bastis are physically distinct, with tile-roofed huts made of brick, earth and wattle (Wattle is a framework made of sticks and twigs; hence the term in building wattle-and-daub, for earthen walls where earth is applied over the wattle.), and are generally poorly serviced in terms of water, sanitation, sewerage, drainage and waste disposal.

The metropolis grew around the colonial port, trading and administrative hub. Large numbers of laboring people were absorbed in factories, manual labor and domestic service. An arrangement developed that eventually led to a unique three-tier tenurial structure. A landlord would, typically, rent out vacant plots under his ownership to members of his retinue, who in turn built a large number of huts on the plot. Rooms in the huts were rented out to the laborers. As this part of the city attracted more people and started getting civic improvements, the landlord would have these plots vacated and sell them for a handsome gain. The laboring tenant dwellers were then forced to move on to another site.

This arrangement, and the informal settlements or bastis, ensured that a place existed in the city for its laboring population, albeit an insecure one. However, with no investments being made by either the landlord or the civic authority, the deplorable basti conditions were viewed as a threat to public hygiene. Colonial Calcutta saw frequent basti demolitions in connection with civic improvements benefiting its affluent citizens; these were usually inspired by public health goals. But the plight of the labourers, and the question of their shelter, was never substantively addressed.

By the time of India’s independence in 1947, the metropolitan area had a large number of bastis that had been in existence for a considerable period of time and housed the overwhelming majority of the city’s low-income, laboring and poor people. Calcutta has a unique demographic feature of being home to a large number of single male migrant laborers from the eastern hinterland, e.g. in the jute factories. The bastis accomodated them, as well as others with their households, extended families and kin networks.

With the influx into the city of a huge number of refugees after the partition of India in 1947, bastis were severely overcrowded. The largely unresolved question of responsibility for civic services in bastis meant that living conditions were deplorable. Post-independence legislation curtailed the rights of the landlords, while granting secure tenancy rights to the intermediate (land-renting, hut-building) tenant. A communist-led movement in the 1950’s that focused on the shelter rights of the basti dwellers, coinciding with the development of national ‘slum clearance and improvement’ legislation, ensured that all dwellers were entitled to resettlement in the event of basti demolition. Bastis were brought under the purview of the Slum Act, which was introduced with a view to enabling provision of basic amenities to the dwellers.

Traditionally bastis have been the sites of a large number of small industries and crafts. Before the development of automobiles the transport system was almost entirely in the hands of the basti people. They controlled the milk and cattle market and the horse market. They also housed the masons and construction workers.

All these trades and crafts catered to the needs of the city and also areas far beyond. But there has also been a persistent process of the basti people, and especially Muslims, losing their independent occupations and turning into wage earners under those possessing superior financial resources and networks. The city’s development and economic blight has meant continuing marginalization for the laboring population. Garment-making, footwear, paper and stationery are some of the sectors that are still based in large Muslim bastis in the city. But given the unorganized nature of these trades, workers and small traders are at the mercy of middlemen and large traders. Lack of access to capital and hence reliance on high interest charging money-lenders; lack of proper marketing opportunities; lack of skill and technology upgradation - are some of the principal problems affecting the trades. Given that all these trades together employ tens of thousands of workers, their vulnerable situation poses a severe threat to their livelihood and hence also to the city’s social stability.

From a social planning perspective, bastis are significant because the bulk of the city’s vulnerable population resides here, in a concentrated manner. This includes Hindus and Muslims. On the whole, basti dwellers are not the poorest of the poor, though many very poor people may also be found. They are subject to marginalization by socio-economic forces; but, by virtue of having a legally recognised foothold in the city - their basti tenant status - and the stability that this brings (in comparison to less fortunate, unrecognized squatters), it is possible to think about their social development.

Basti Improvement

Following a WHO study on Calcutta in the early 1960’s, which expressed serious concern about public health risks - in particular those arising from conditions in the bastis - a high-level planning effort to rescue Calcutta was taken up, with the support of the Ford Foundation. A Basic Development Plan (1966-86) was prepared. The Calcutta Urban Development Programme was taken up from 1970, with assistance from the World Bank. Basti improvement was a major element in this.

The Basti Improvement Programme (BIP) aimed at conversion of unsanitary toilets, provision of water taps, surface drainage facilities, construction and widening of roads and pathways, and provision of street lighting and waste disposal facilities within the bastis. After the coming to power of the Left Front government in the state of West Bengal in 1977, most basti lands were taken over by the state. But the right of the state to carry out developments on this land was impeded by a court ruling upholding the right of the intermediary tenant to undertake improvements to the existing basti structures. Through new legislation, the rights of the intermediate tenants were restricted, while the tenure security of the tenant dwellers remained protected.

Bastis improved under this programme are today once again facing acute deficiencies in services. Toilets constructed to be used by 25 people, may today be used by as many as 300-400 people. Maintenance of the infrastructure is a major problem. Overcrowding is rife. Since the mid-1980’s, improvement works in bastis have been the responsibility of the local municipal bodies. Drainage or sanitation improvement works are the sole responsibility of the local body, which is not in a position to undertake these. Given the chronic fund shortages in the local bodies, and severe institutional malfunctioning, today bastis are under acute stress. It is likely that bastis will simply degenerate further. The whole question of basti conditons, and the issue of initiating sustainable improvements - is a very pertinent one.

Displacement of the Laboring Poor

Bastis present a further major challenge for policymakers. Ultimately the improved housing is taken over by relatively better off people. The burden of the overall housing shortage in the city is borne by those at the bottom. The tenant basti dwellers are in a situation of insecurity as the housing scarcity and real estate forces work to push out the poor and low income - either to fringe areas, or to unrecognised dwelling. Sooner or later the imperative of strategic redevelopment of basti lands has to be acted upon.

However, this can mean the complete displacement of a huge population, with devastating social and economic consequences for the metropolis. Lessons have to be learnt to avoid repeating the negative experiences in Bombay, where, since 1991, the attempt to undertake slum redevelopment on the basis of land sharing, through private developers, meant that insecurity, intimidation and even violence was unleashed upon the slumdwellers. Thus, basti redevelopment, that is led by an empowered community acting through a capable local institution, is the objective that has to be worked towards.

But today, bastis in Calcutta do not offer any hope of such tenant-led development. The principal actors so far have been political parties and the state, with some philanthropic agencies and community-based organisations undertaking welfare activities. Basti dwellers are not organised as a class, and in the bastis it is the intermediary tenants, building developers and their allies (often political party activists in league with muscle-men ) who are more powerful. Given that bastis are spread all over the city (rather than in a separate shanty-town), basti lands are very valuable. The major success of the BIP has been in reinstating these settlements in the land market. With the existence of a large unmet demand for housing among the lower-income groups and middle class, the blighted bastis represent a site for considerable profiteering through illegal building construction, and thus attract ‘money power’ and ‘muscle power’. The tenant dwellers are the most vulnerable within this environment.

Crime and Politics

Slums have also to be understood in the light of the growing criminalisation in these localities. Bastis may be the sites of a considerable amount of illegality and crime. Illegal building construction is a major activity.

All this takes place blatantly, with political protection and involvement of the authorities. It is part of the common knowledge of people in bastis that the local members of the ruling party are closely involved in all this. With them ruling the roost in most localities, over the years a terrible lawless, corrupt, rowdy environment has grown. Common people prefer to stay out of any trouble and remain in the background. Thus, a cloud of fear and violence hangs over the community.

Generalized society-wide youth unemployment, breakdown of social values, rising material aspirations and growing consumption, widening socio-economic disparities, mass media exposure, impatience among youth with traditional values, together with criminalization of politics through political protection of criminals, endemic corruption, the police-crime nexus - it is in this context that one can begin to understand the socio-cultural environment in bastis today.

Party politics at the grassroots level is about power, for oneself and those one considers one’s own. Power can mean material benefit, besides being in a position to do what one might want, without any disruption. Having power means being able to appease a few people, and thus remain in power. Gratifying some also helps to keep them in obligation, for repayment in one form or another - donations, participating in party rallies, voting for the party and getting one’s friends and relatives to also support the party, joining the party group in its conflicts etc.

There is a vast gulf between the senior leadership in the party and the basti-level party workers. The latter view themselves as local lords, free do to as they choose. They intervene in all affairs in the basti, in order to ensure their total dominance. And ordinary people try to keep themselves away from any trouble or conflict. Hence the dominance of the party activists.

Calculations for the party are only in terms of numbers - who will be affected by any step, who will gain. What is correct, or legal is of no importance in such a context. In this milieu, the predominant urge in any situation is to gratify, or benefit, to gain or seek support. What is right, or correct, or legal often gets obscured as a result.

Higher-ups in the party do not have a personal base in the basti, nor would they like to devote any of their own time or efforts here. Hence party affairs are entirely in the hands of the local unit. They are a kind of local broker to deliver the bloc vote of a community living separate and segregated.

Within the party, there are groups and sub-groups, with allegiances being flexible in line with emerging circumstances. Thus petty politicking, factionalism, cliques, and continuing conflicts, sometimes mild, sometimes serious, as attempts are made to settle scores - this is a key feature of the local environment.

Ultimately, patronage to criminals is simply a practical thing to be done by any political party. In their view, only this can ensure that there are ‘fair’ elections. Also, it is only with the help of muscle-men that any party can be in a situation of complete dominance locally. Thus, politicians and criminals help each other to survive and thrive. Senior, committed leadership within the party is quite aware of and concerned about the situation in basti localities. But they are unable to act forcefully because the party is severely compromised.

For ordinary people, their social background and personal circumstances serve to render them powerless and keep them dependent upon others for the smallest matters. This also means that efforts made on vital matters - such as water supply or electricity - follow community-level practices. Thus, if at all someone decides to do something, they would typically approach one or other of the local power wielders for help. The means through which such a powerful person helps the needy one would be inherently individual-oriented rather than community-oriented, creating dependence rather than independent capability, and often, illegal rather than legal.

There does not exist at this juncture any prospect for any positive improvement, in fundamental terms, in the living conditions of the people in bastis. Nor does there exist any institution, organisation, entity, actor or individual, who is capable and committed enough to take up a long-term improvement-oriented programme.

The prospect for united action by households at large, and especially the poor households, so as to seek, pursue and secure sustained improvements in their socio-economic and environmental stakes and thus be successful in mitigating the poverty and environmental degradation confronting them - is extremely remote.

Women, and poor women in particular, emerge as the worst sufferers. In the existing psycho-socio-cultural milieu of bastis, the prospects for united action by poor women, to secure improvements in environmental services, in collaboration with people and groups from the wider basti and community - are virtually zero.

Communal Riots

Calcutta is also the city that witnessed the Great Killing of 16 August 1946. Bastis had been the centres of major communal riots between Hindus and Muslims during 1945-47, and again in 1950. Post-riot analyses dwelt upon the degraded conditions prevailing in the bastis, which led to the build-up of rage that erupts in riots. In December 1992, some Muslim slum areas of Calcutta were rocked by communal riots following the destruction of a mosque in Ayodhya. Looking from within a basti, it is possible to begin understanding how and why riots actually take place, in the context of the politician-criminal nexus that thrives on deprivation and disempowerment.

For the ruling state government, preventing communal riots has become a matter of utmost importance. Given that it is Muslims who are ultimately worst hit by riots, this commitment by the state is indeed commendable. However, despite being in power for 25 years, the state government has been unable to do anything about the steady social and economic disempowerment of Muslims.

Owing to the lack of direct control of senior party functionaries over basti matters, local criminalised cadres who face obstructions from the party are in a position to blackmail the party higher-ups by giving a communal colour to any matter going against them and inciting a small-scale riot if necessary to press their point home.

Slum environments are sites within which communal riots are manufactured. Hence the challenge, of making a breakthrough in empowering basti dwellers.

The Unintended City

In 1975, Jai Sen, an architect-planner, wrote an influential essay titled ‘The Unintended City’. He argued that hidden within the commonly perceived ‘respectable’ city, of wealth, institutions, planned improvements, intellect and culture, was another city, an unintended one, of the laboring poor. This city was characterized by the survival struggles of its inhabitants. Every planned improvement for the ‘intended’ city also necessarily meant displacement and hardship for the unintended. It was the unintended who ensured that a range of services and products were available to the city; in a sense, they subsidised the quality of life of the citizens, through their own deprivation.

Sen called for a programme of empowerment of the unintended, through community-based action-planning initiatives. Such initiatives could become the basis for a holistic understanding of the city, and hence a planning intervention that sought to advocate the interests of the unintended and integrate such concerns with the formal planned developments. And thus lead to the transformation of such planned development itself, as well as of the cityscape and its social relations.

Sen started a social action group in 1977, called Unnayan to take up an ambitious, long-term programme in east Calcutta, which was just about to witness major infrastructure investments by the state government in middle-class housing, water supply, drainage, transportation and electrification. Unnnayan anticipated that the process of displacing development would again result and sought to intervene in such a context - towards enabling a future for east Calcutta that would be more in keeping with the lives and aspirations of the marginalised laboring communities settled there.

By the end of the 1980’s, Unnayan’s work had grown to cover social and technical support initiatives to a number of poor communities across Calcutta. It took an active part in the formation of the Chhinnamul Sramajibi Adhikar Samiti (Organisation for the Rights of Uprooted Laboring People), an umbrella under which local committees from squatter settlements across Calcutta came together in 1984 to take up a campaign against forced evictions and demolitions, and more generally to press for recognition and regularization or resettlement. A national workshop on the housing question was organized in 1985. Legal strategies and actions were taken to advance the housing rights of unrecognized dwellers. Persistent advocacy was taken up, at city, state, national and international fora. Unnayan played a key role in the formation of the National Campaign for Housing Rights (1986) and the Asian Coalition for Housing Rights (ACHR, 1988).

Unnayan networked with organizations and individuals in the city and nationally, and tried to bring into this fold other groups such as political activists, trade unions, professionals, academics and sections of the intelligentsia, civil liberties organizations, cultural activists and groups, NGOs and other social movements.

Through all this, in the absence of any other institutional effort on the crucial public domain issue of rights and social development of the city’s laboring poor, an ‘alternative’ planning perspective had entered the public space.

Unrecognized Settlements

Unrecognized or squatter settlements on vacant land on the margins of city infrastructure began to emerge in Calcutta from the early 1960s. It was a result of stoppage of basti expansion in the post-Independence era, the insignificant role of public housing schemes in providing for the low income and economically weaker sections, and the absence of any private sector mass housing programs.

There is no authoritative official data on dwellers in unrecognized settlements - along rail tracks, canals, highways, under bridges and flyovers and on vacant public and private land. Broad-brush surveys undertaken in the mid-1980s by Unnayan estimated the number of unrecognized dwelling, of all types, at between 5 -10% of the metropolitan population.

These settlements are viewed as ‘unauthorized’ or ‘illegal’ and are hence entirely unserviced. The fear of eviction and demolition looms large over them and serves to inhibit any community initiative to improve housing and settlement conditions. Their ‘unauthorised’ status is in effect a means for the complete disenfranchisement of these communities.

Unrecognized settlements represent some of the most degraded environmental conditions, with severe health impacts for the people living there, and with potential larger public health consequences as well. Given that most unrecognized settlements in the metropolis lie on the margins of infrastructure features, like canals, rail tracks etc., the relevance of in situ regularization here is questionable. Resettlement in a new location also poses serious difficulties. Residence for such dwellers is closely related to livelihood opportunities, and hence relocation could be disruptive unless the resettlement program includes economic rehabilitation. That requires considerable external support, and puts the people into a situation where their dependence on others is increased.

A Pluralist Perspective

In 1995, with support from ACHR, Unnayan took up a project to prepare a proposal substantively addressing the issue of unrecognized settlements in Calcutta. Based on an analytical understanding of the larger question of the housing situation in Calcutta, I developed a proposal (on behalf of Unnayan) looking at this - rather than just the squatters’ question. They represented only the most visible, raw end of the problem, which, however, affected large numbers of people of other classes as well. Not addressing the question of supply of shelter to middle and lower income groups would mean increasing the pressure on the space in the city occupied by the laboring poor, eventually leading to their displacement.

Thus arose the imperative of viewing the middle-class, low-income, poor and vulnerable section as a whole. It is basti renewal that can make available land to resettle squatters, while also providing a powerful beginning to city renewal itself.

A proposal was developed for comprehensive area renewal in the blighted canalside region of Calcutta. This was well within the ‘city improvement’ paradigm of government and developers, but emphasized, up-front, the normative social and environmental goals for which a part of the surpluses generated through the renewal needed to be channeled. A purposeful utilization of the real estate market mechanism, to achieve public goals for the city.

All the erstwhile residents, and especially the low-income and poor, would get new, better and affordable housing. This required maximization of net built-up area, which could be sold at the highest market rates. The most fundamental aspect of this renewal proposal was organizing the poor communities. Calcutta simply did not have the institutional wherewithal for this. A new generation of institutional forms needed to come up, to take up the immense social development agenda that would arise if bastis were to be developed in the interests of the dwellers. In turn, such social investments would directly lead to the large surpluses potentially available through basti redevelopment.

Calcutta Environmental Management Strategy and Action Plan (CEMSAP)

The Calcutta Environmental Management Strategy and Action Plan (CEMSAP), a project of the Dept. of Environment, Govt. of West Bengal, was a strategic initiative for long-term environmental improvement in the Calcutta metropolitan area, supported by the U.K. aid agency, the Department for International Development (DFID),. CEMSAP’s Social Development group focused on the vulnerable sections, seeking to promote greater social justice in environmental improvement efforts.

As the project’s Social Development Coordinator, I developed the Community Environmental Management Strategy and Programme. Basti development was identified as the key action issue for achieving sustainable environmental improvements to benefit the vulnerable sections. Given the silence and capability vacuum in this regard as far as the formal institutional were concerned, capability-building for community-based environmental management in bastis was seen as a strategic imperative for advancing the cause of dweller-led basti development. I also led CEMSAP’s ‘pilot project’ on participatory environmental improvement in slum pockets of Howrah.

Howrah Pilot Project

In 1997, as an independent follow-up to CEMSAP towards long-term redress in Howrah, one of the most blighted cities in the world, I established the Howrah Pilot Project (HPP). The goal was community, slum and city renewal beginning from the poorest and most socially and environmentally degraded slum localities.

Through the efforts of HPP, on International Women’s Day 1998, Idara Ittehad-ul-Khawateen (IIK) which means the Organisation of Women’s Unity, was formed under the spirited leadership of a group of young women volunteers from Priya Manna Basti in Howrah. This is a century-old jute workers’ settlement of about 50,000 people, mainly laboring, Urdu-speaking Muslims.

About 10 % of the households in Priya Manna Basti are in the poorest category. Typically the bread-winning male would be a daily wage earner performing manual labour, petty vending, rickshaw-pulling etc to earn Rs 50 - 100 per day ($ 1-2). Family size is large, with at least 5 children being the norm, and in some cases more than 10. Shelter consists of a single (rented) room of about 100 sq ft. The physical environment is degraded, with a high degree of overcrowding, inadequate drinking water, very poor sanitation, drainage and waste-disposal. Health conditions are poor, with high infant mortality and morbidity. Primary education is rarely availed of, and children begin working from as early as the age of 5, within the household or outside. Lacking vocational skills, livelihood options for youth, and especially girls, are extremely limited. A range of piece-work production activities take place, with very low remuneration. Girls get married by the age of 16, and continue to raise children in the same manner. Illiteracy is almost universal in this poorest class.

Such an environment also breeds and hosts petty crime and anti-social activities as well as major, violent crime. Political parties have a powerful presence in such an environments, mediating civic improvements and community conflicts and stifling independent community action. They are also often closely linked to criminal elements.

The life of the poorest households revolves around daily survival in the margins of society. There is a conservative attitude regarding female education and movement outside the house among the uneducated sections of the Muslim community.

Idara Ittehad-ul-Khawateen has initiated and managed through its squad of young women volunteers a range of community development efforts in and around this slum, targeted at women and children from the poorest households. This includes literacy and social and health awareness for women, a non-formal school for poor and working children, a vocational training program for girls, a thrift-and-credit program, linkages to health services and livelihood enhancement efforts.

IIK works as a vehicle for community awareness and development, for the betterment of the quality of life of women and children in the poorest slum households, and to build communal amity. In the process, a grassroots organization is being built and its capabilities developed so that it can work effectively and in a sustained manner for its objectives.

Metropolitan Assembly for Social Development (MASSDEV)

Inspired by the HPP program in Howrah, the Metropolitan Assembly for Social Development (MASSDEV) was established in 2001 by a group of concerned citizens in Calcutta to work purposefully for all-round community development in the basti localities in the metropolis.

The objective is to catalyse, facilitate and guide effective community development programs under the leadership of capable local organizations. The main focus of MASSDEV would be on economic uplifting of the poor, through a network of vocational training and production centers supported by a marketing effort. Local-level ownership of initiatives and efforts in this direction through committed and capable community organizations would be complemented by a central, facilitating, training and linkage effort through MASSDEV.

The work of MASSDEV would be to build, sustain and strengthen long-term efforts for the empowerment of the laboring poor and vulnerable sections. This would take place principally through capable community organizations in basti localities. As a pluralist, metropolis-wide, civic integrating platform, MASSDEV would seek to enable the building of civil society and grassroots ownership and practice of action for social and environmental justice in the Calcutta metropolitan area.

A similar initiative has been undertaken since 1995 with very positive results in the slum areas of the old city in Hyderabad, through the Confederation of Voluntary Associations (COVA). COVA is closely associated with the efforts in Calcutta.

MASSDEV may be seen in the light of the current situation regarding public domain institutions in Calcutta. The institutional infrastructure remains to be built for the critical grassroots and civic roles vital for sound urban governance and environmental and social justice. Pro-poor city renewal, at a metropolitan scale, is principally hostage to this systemic deficiency.

MASSDEV may also be seen in the context of the forthcoming city infrastructure, slum improvement and poverty reduction projects in Calcutta, under the aegis of the World Bank, Asian Development Bank (ADB), DFID etc. The earlier slum improvement efforts had failed to build any systemic institutional capability for socio-economic-habitat development at the slum community level. So all these new projects would require active and capable community organisations, resource organisations and civic fora. That cannot be built by the project funder or the recipient state or local government, though the process of building this institutional infrastructure could be facilitated by the government.

The challenge for the citizens of Calcutta is to exercise effective and capable ownership of the public domain concerns of social and environmental justice.

V Ramaswamy is a Calcutta-based business executive, public policy consultant, community development worker and teacher. He has been associated with a number of social and people’s organizations, campaigns and movements. He is Chairman of Howrah Pilot Project and Secretary of the Metropolitan Assembly for Social Development, Calcutta. He is also a Public Policy Associate at the Jerusalem Institute of Urban Environment, a visiting Master at the Rashtriya Indian Military College, Dehradun, and Guest Faculty in the Department of Architecture at Jadavpur University, Calcutta. Click here to e-mail.

Achinto Bhadra is a Calcutta-based photographer who has documented extensively life, labour, habitat and community in India's villages and towns. He has undertaken assignments for international development agencies and NGOs. His work has been critically acclaimed and been published and exhibited in India, Europe and America.