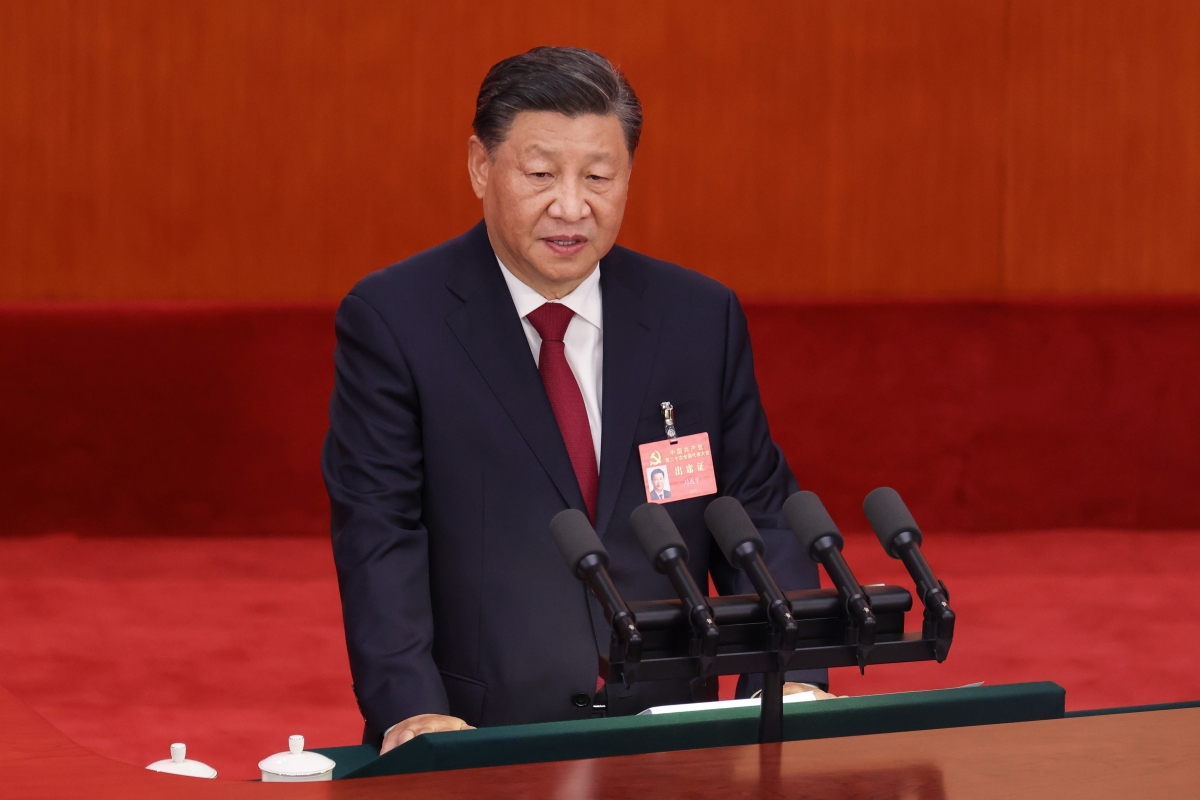

Xi Jinping’s 2022 Work Report: The Return of Ideological Man

Xi Jinping’s “Work Report” to the 20th Party Congress provides an ideological and political framework for understanding the likely direction of Chinese domestic and foreign policy for the next five years. It is a report that underscores Xi’s Marxist-Leninist worldview — a worldview that also drives his nationalist ambition of making China the preeminent regional and global power by mid-century. The report also makes clear that the shift in economic policy direction over the last five years (back to the state and a retreat from the market) will continue over the next five years. More disturbing, however, is the document’s formal conclusion that China now faces an increasingly adversarial external environment and that the country’s national security establishment and the People’s Liberation Army (PLA) should be increasingly prepared for “the storm” which lies ahead. Finally, Xi’s report makes abundantly clear the delineation between this “new era” of ideology, statism, foreign policy assertiveness and national security vigilance — and the rolling political and policy pragmatism of the Deng Xiaoping era which preceded it.

The Role of Ideology

Ideology has always mattered to the Chinese Communist Party. But with Xi Jinping, we have seen the return of Ideological Man with his own brand of Marxist-Leninist nationalism. This was clear from Xi’s earliest writings in 2013 which resulted in the reassertion of the Party’s Leninist control of Chinese politics. His Marxist ideological worldview began extending to the economy after the 19th Party Congress in 2017 when he formally redefined the Party’s ideological priorities away from the rip-roaring days of unconstrained “reform and opening” to develop the economy, to a new era dealing with the “imbalances of development” which the Deng Xiaoping, Jiang Zemin and Hu Jintao periods had created.

The 20th Party Congress report is more ideological in tone and content than we have seen in congress reports for the last 40 years. The report speaks to the great ideological progress which has been achieved over the previous decade in developing a “new chapter in a modern Marxism for the 20th century.” He enjoins the party to “grasp both worldview and methodology of Socialism” and to apply the analytical tools of dialectical and historical materialism to the Party’s understanding of the great challenges of the time. Indeed, this ideological lens should be applied “to advance every aspect of our work” — and in so doing, also develop “a new normal for the civilization of all humankind.”

Chinese Communist Party officials (for whom the work report is intended) are acutely attuned to changes in the ideological phraseology of these core party documents. This goes down to an analysis of basic word counts for particular phrases. For example, the term “Marxism” itself is referred to 26 times in the work report — double the number that we saw in the already ideologized report of 2017. The Marxist-Leninist concept of “struggle” (violent or non-violent) as the means by which to realize domestic or international progress against the Party’s stated objectives, has 22 references in the report — about the same number as in 2017. The Marxist concept of “common prosperity” is also emphasized in equal measure compared to the 2017 document. But Xi Jinping’s overriding nationalist objective of building a powerful state (qiangguo), together with the term “Marxism” itself, represent the dominant ideological thematics for the 2022 report: there are 32 references to a “powerful state” in 2022, versus 20 such references in 2017.

State versus Market in the Economy

On the economy, the central question has been whether development remains the central task of the party or whether that has now been equaled (or even surpassed) by national security. One indication of the shift away from the absolute centrality of the economic growth agenda lies in the number of references to the simple term “the economy” in the text of the 2022 report compared with its predecessors. In the 14th Congress report in 1982 when Deng relaunched his economic agenda of market reform and opening, the term “economy” was referenced 195 times. By the time of Xi’s first Congress report in 2017, that number had come down to 70. In this report, “the economy” is referenced on only 60 occasions. This declining emphasis on economic development is also reflected in the report’s somewhat tepid treatment of the Party’s growth objectives for the 5 years ahead; the CCP now aspires to only “reasonable growth rates,” presumably mindful of the vast array of domestic and international headwinds now bearing down on the Chinese economy.

The qualitative treatment of the Party’s economic policy settings in this Congress report also indicates a continuing drift away from market principles back towards the more comfortable disciplines of state direction and control. Whereas the report does make reference to an earlier party mantra of “giving full play to the decisive role of the market in resource application,” this continues to be tempered by parallel reference to the need for “a better role being played by the state.” The same sort of parallelism is evident in the report’s treatment of state-owned enterprises and the private sector: the party is told to “consolidate the public economy” while simultaneously “encouraging the non-public economy.” The report also speaks of the need for “national self-reliance” in science and technology, the “strategic” allocation of resources for the development of new technologies (rather than sharing that remit with China’s dynamic, privately-owned tech sector). The party is also directed to undertake the strategic deployment of human capital, rather than talent being allocated according to the competitive opportunities of the market. There are also numerous references to China’s new mercantilism as reflected in the impenetrable dogma of the “dual-circulation economy” whereby China’s future growth drivers are seen to be largely domestic, although net exports are still encouraged in order to increase foreign dependency on the Chinese market. This is reinforced by a call to “increase the security and resilience of China’s own industrial supply chains” in anticipation of future national security challenges. Moreover, all of this is compatible with Xi’s embrace in his congress report of a “high level of opening to the outside world” in contrast to the unconditional formulations used during the Deng period on the centrality of “reform and opening,” long seen as being central to China’s growth performance in the past.

This statist emphasis on China’s unfolding economic model is tempered by a limited number of more reformist concepts. For example, there is a new call to increase total factor productivity across the economy although little indication is given as to how this might be achieved in practice. Similarly, there is an indication that China will reduce the exclusion list for the categories of permissible inbound foreign direct investment for the future. Just as there are references to China’s desire to bring about “the increased internationalizing of the renminbi” — although this would appear to be part of a more general strategy to reduce China’s future international dependency on global financial markets which continue to be denominated in US dollars. China is mindful of the consequences of financial sanctions applied against Russia following the invasion of Ukraine — and what that might imply for any future Chinese military action over Taiwan. Nonetheless, whatever pro-market signals might be contained within these measures, they are qualified by Xi’s new, overriding ideological narrative of “a Chinese style of modernization.” This represents an implied critique of neoliberal globalization. It also reflects Xi’s embrace of what is now termed the “correct direction of globalization” for the future.

Xi’s New International Threat Perception: Putting China onto Long-Term Military Alert

The most disturbing component of the 20th Party Congress report, however, lies in its formal analysis of China’s rapidly evolving external strategic environment. In previous Party Congress reports back to the 1990s, there has been a standard reference to “peace and development” as the major, underlying trend of our times. Indeed, a benign external environment had long been seen by Deng and his successors as the analytical underpinnings for China focusing exclusively on its economic development imperative. This formulation was complimented by another standard phrase in Congress reports since 2002 that “China was experiencing a period of strategic opportunity” (zhanlue jiyuqi). Critical to this analysis is that neither of these standard expressions feature in the 20th Congress report. The analytical and policy implications of this conclusion are clear. The party no longer rules out the possibility of major war in the future. As a result, the party’s security agenda now rivals and perhaps surpasses the central priority attached to its economic agenda over the previous 40 years.

This conclusion is reinforced by a new set of formulations that lace the document’s analysis of China’s rapidly development external environment. Xi now describes a “severe and complex international situation” where the party must be “prepared for dangers in peacetime” as well as “preparing for the storm” (jingtaohailang). In doing so, Xi also calls on the Party to continue to adhere to “the spirit of struggle.” And in all of this, Xi refers to the next five years as “critical” for the continued building of a powerful Chinese nation. The Congress report goes on to refer to “national security” as the “foundation of national rejuvenation.” Xi also uses the Congress report to entrench earlier statements he has made on the need for “a total security agenda” incorporating ideological security, political security, economic security, and strategic security. The report then directs the party to apply this concept of “total security” across the full spectrum of the Party’s internal processes. As for the PLA, Xi calls for “an increased capacity for the army to win;” an “increased proportion of new combat forces;” and for the promotion of “actual combat training for the military.”

Importantly, however, the Congress report’s language on Taiwan is relatively conciliatory. Xi emphasizes the Party’s preference is to resolve the Taiwan issue peacefully, while not renouncing the use of force. This is not a new formulation. What is new, however, is Xi’s warning that its harsher measures over Taiwan are targeted not at the bulk of the Taiwanese population, but instead at the small minority of Taiwan independence supporters and those foreign states (i.e., the U.S.) that back them. Xi nonetheless reminds his Taiwanese audience that on the broader question on reunification, the forces of history are still grinding forward toward the “inevitability of reunification.”

The Individual Political Power of Xi Jinping

Finally, on the pure politics of the 20th Party Congress report, the document represents a further elevation of Xi Jinping’s paramount political status within the party. On a close reading of the report, Xi seeks to surpass Deng’s standing by effectively replacing the latter’s “four cardinal principles” on party control with his own “five important principles.” The latter adds a new, fifth principle on the importance of “struggle,” a term which in itself represents a partial resuscitation of an earlier Maoist legacy.

Second, there are also new Xi formulations on the enduring question of the longevity of the party’s governance over China, given Mao’s earlier preoccupation with China’s long imperial legacy of the rise and fall of dynasties. Mao’s response to this dilemma in the 1940s was his concept of “the People’s continuing supervision of the Party” in order to prevent it from becoming detached, bureaucratized, and corrupt. To this, Xi has added a further answer to Mao’s earlier question in the form of his doctrine of “self-revolution” (ziwo geming) whereby the Party deploying its own internal rectification, anti-corruption, and other surveillance mechanisms could potentially sustain itself in political power indefinitely.

Third, Xi dedicates a lengthy section of his report on the party’s achievements over the last decade under his own leadership, which are listed as “the great changes of the new era.” The list is a familiar one. It ranges from the consolidation of the Party’s leadership overall, the confirmation of China’s new middle-income status, the evolution of his new development concept as an alternative to Deng’s era of reform and opening, the elimination of poverty, the proper handling of COVID-19 (albeit without any indication in the document on a future transition from China’s “dynamic zero COVID approach”). Internationally, it includes the resolution of the Hong Kong problem by placing the special administrative region (SAR) “in the hands of Hong Kong patriots;” the international acceptance of the Belt and Road initiative, and dealing effectively with a rolling series of drastic changes in China’s international operating environment. The net impact of these three records of achievement is to elevate Xi’s ideological status as he heads for his third and by no means last five-year term.

Therefore, while we are still several days away from seeing any further additions to Xi’s leadership titles, or any further elevation of “Xi Jinping thought” into the Party’s canon of ideological orthodoxy, as well as the composition of the slate of new appointments to the Politburo and its Standing Committee, what we see in this 2022 Work Report are the ideological foundation stones being laid for Xi’s long-term elevation within the Chinese Communist Party pantheon. Xi is now described as a more significant leader than Deng. And also as one beginning to acquire co-equal status with Mao as he leads China from having stood up in the eyes of the world in 1949; to having become wealthy during the period of reform and opening between 1978 and 2017; to one which now seeks under Xi’s “new era” to now become the most powerful country in the world over the next quarter of a century.