China’s Economic Downturn Gives Rise to a Winter of Discontent

The Wall Street Journal

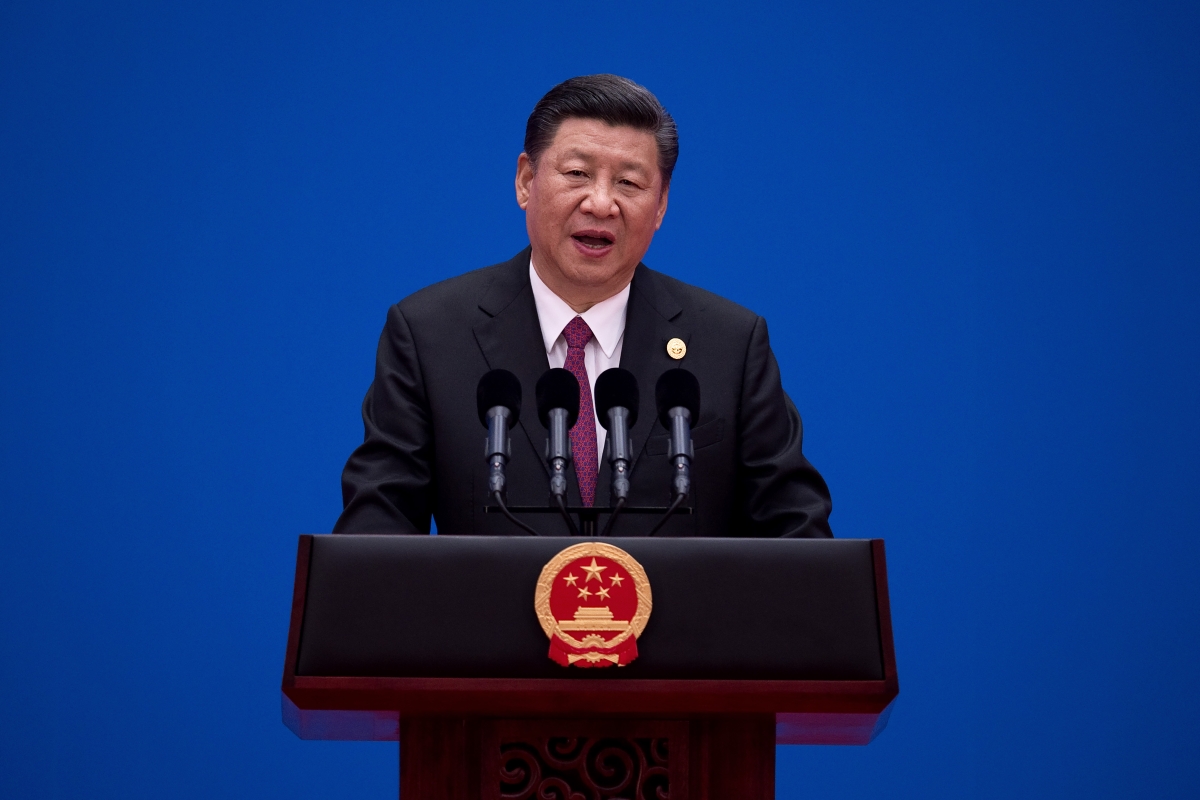

(Photo by Nicolas Asfouri-Pool/Getty Images)

(Photo by Nicolas Asfouri-Pool/Getty Images)

The following is an excerpt of Kevin Rudd's op-ed originally published in The Wall Street Journal.

China’s economic future isn’t looking all that bright and is starting to have political implications for President Xi Jinping. The Chinese Academy of Social Sciences expects annual growth to slow to 5.3% in 2022 from 8% in 2021. Real-estate giant Evergrande, declared in default last month by ratings agencies, unleashed a wave of defaults in the country’s property sector, which is worth about 29% of gross domestic product.

Evergrande, with $300 billion in liabilities, is only the tip of the iceberg — one of many problems flowing from economic-policy decisions made in Beijing. Political reverberations of those decisions are emerging in China’s official media.

China’s most important annual economic meeting, the Central Economic Work Conference in December, revealed a debate roiling between reformists and more-conservative officials over whether the market or the state can more efficiently allocate capital and economic resources.

Policy documents from the most recent CEWC — where senior Communist Party officials convene — included a loosening of Mr. Xi’s flagship “Common Prosperity” campaign. The effort to ease wealth inequality included a crackdown on many of China’s richest private-sector individuals and enterprises and stoked fears of a witch hunt against the wealthy. Policymakers at December’s CEWC meeting, while grappling with slower growth, concluded this may have been an overreach and said Common Prosperity should be more of a “long-term historical process.” In other words: Now may not be the time to kill the private-sector goose that laid the golden egg.

It is also significant that the directive to “strengthen antimonopoly and prevent disorderly expansion of capital” — which appeared among “Eight Major Tasks” of the 2020 CEWC — wasn’t among the “Seven Major Policies” of the 2021 meeting. Instead, policymakers focused on achieving macroeconomic “stability” in 2022. This change in messaging appears designed to assuage China’s massive fintech firms, which Mr. Xi has targeted over the past 18 months.

This is a crucial year for Mr. Xi because he will likely seek a third five-year term at the Chinese Communist Party’s 20th Party Congress this fall — and then potentially rule for life. Presumably, he wants to prevent any disruption of China’s economic, financial or social stability. But the economic destruction Mr. Xi’s centralization of power has wrought may give his critics leverage that they haven’t had for years.

Beneath the surface of Chinese politics, there is other evidence of a political reaction to Mr. Xi’s attacks on the private sector and his overall negative views on the role of the market.

Read the full article in The Wall Street Journal.