Paul Auster: Lost (and Found) in Translation

American novelist, Japanese translator on cross-cultural communication

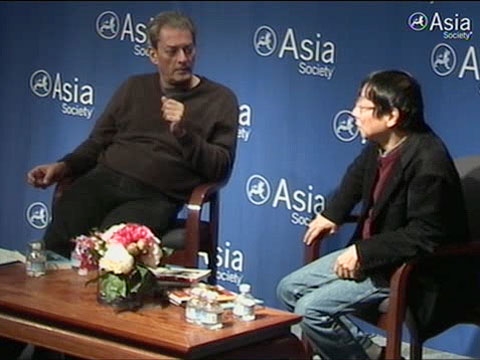

NEW YORK, December 7, 2010 - Two writers shed light on the nuances of translation and its importance in cultural communication at the Asia Society, as internationally renowned novelist Paul Auster and his long-time translator Motoyuki Shibata appeared together publicly for the first time to talk about their ongoing collaboration.

The conversation had the intimate quality of overhearing two old friends getting to know each other after years apart as they ranged across film, baseball, and everything in between.

As an introduction, Auster read the opening paragraphs of his novel Oracle Night, after each of which Shibata read his translation in Japanese. The subtle changes of rhythm, cadence, and breath hinted at the profound differences of both languages and at the daunting task of translating someone else's art.

Shibata then spoke about his early exposure and progressive interest in American literature and culture. In response, Auster shared his first, vague impressions and concept of Japan as a kid growing up in post-WWII America. Years later, his love of Japanese film and literature as well as his experience as a judge at a film festival in Tokyo consolidated his current understanding and curiosity about the culture.

Both writers expressed their interest in translation and different cultures as formative to their craft. Shibata's work developed partly from the curiosity of whether or not translation can accurately express the tone and style of a work. Auster taught translation classes and has translated the works of French writers extensively. "Translation is a great thing for young writers to do; every young writer should try to do it... (It's) the best way of reading," he elaborated. "You have to understand a text completely before you try to translate it. Then you have to dismantle it, completely take it apart, and then build it back up again in a new language."

Shibata offered a narrative description of what he does. "I visualize the act of translation this way: a bunch of kids are on the street, there is a wall and beyond the wall there is something interesting going on. There is a ladder, and only one kid can go up there and report what is going on to the rest of the kids. This kid, this privileged kid, is like the translator.”

As to the cultural benefits of translation, the answer was clear. Auster explained: "It seems to me that there can't be a writer living today who is any good or of any interest who hasn't read outside of his own culture. It would seem impossible. You can't be a 21st-century writer and not have read Flaubert or Thomas Mann or any number of great writers... I think in a way we are all living through translations."

The personal tone of the evening seeped into the Q&A session, in which the audience's questions raised a number of issues on the craft of translating. One of the questions triggered a discussion on how translations always age faster than the originals they spawn from and the changing use of language through time.

Another question referenced a line from Goethe, in which the German author compared translating literature to changing the soil of a plant: some literary works are like potatoes that grow anywhere while others are more delicate, like tropical flowers. Both writers agreed and noted the different degrees of difficulty in translation depending on the complexity of a writer's language. Auster remarked that some writers, like Dostoyevsky, travel well, while others simply don't. Shibata noted that Auster's work is highly translatable, to which Auster readily replied, "I'm a potato, that's why."

Reported by Sumie Garcia