Rehabilitating the Last Empress

Jung Chang’s Revisionist Take on Cixi

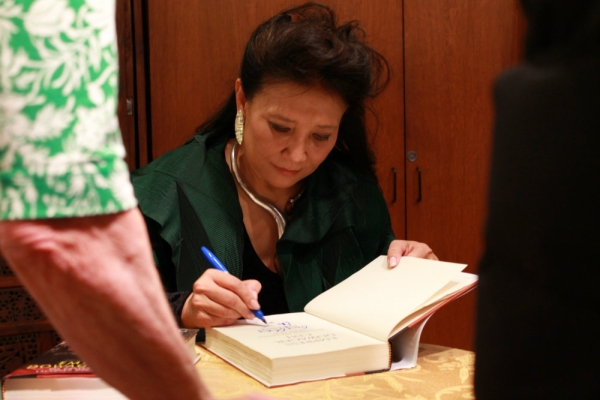

Best-selling author Jung Chang’s newest work, Empress Dowager Cixi, upends the stereotypes of China’s last Empress, who ruled for nearly five decades until her death in 1908. Instead of a cruel, ineffective despot or scheming traditionalist, Chang finds in Cixi a modernizer and proto-feminist determined to remake China as a modern state with a strong military and to free women from the constraints of medieval society. While many of these efforts failed, Cixi was the first Chinese ruler to attempt them. Chang spoke before a standing-room-only audience at an Asia Society-Mechanics’ Institute event on November 18.

Making use of a treasure trove of newly available Chinese-language resources, Chang combed through official records and countless diaries written by members of the court, eunuchs, ambassadors, and ladies in waiting, uncovering everyday details down to the type of rouge Cixi wore.

The story Chang tells is of a pragmatic if often ruthless reformer. Cixi sought to make China modern, with a strong military, internationally oriented economy, and at the end of her life, Jung says, a constitutional monarchy complete with universal suffrange and an elected parliament.

Cixi was certainly not born to rule China. She was first brought to the Forbidden City in 1852 as a low-ranked imperial concubine, albeit one from a prominent Manchu family who could read and write Chinese. She was not considered a great beauty, was not shy about expressing her views, and Emperor Xianfeng, whom she served, did not even like her, Chang said. But Cixi gave him his only son, and she used her growing stature to mount a successful coup after Xianfeng’s premature death in 1861.

Cixi ruled for nearly 50 years, though as a woman in traditional China she could only do so through men (or boys, whom she could manipulate more easily). She was literally “the power behind the throne”, governing from behind a yellow silk screen separating herself from her subjects.

Cixi took power in a period of great uncertainty and change, as China was coming under threat, military and economic, from Europe, the U.S., and later Japan. Cixi, like her contemporaries in Meiji Japan (1868-1912), proposed a program of radical reforms and learning from the West not so much to imitate the West as to resist its incursions. Over her decades in power, she launched a series of often-radical reforms, calling for an end to foot binding, which had tortured Han women for a thousand years, releasing women from their homes into the world, opening China to foreign trade, building railroads and utilities, and pursuing military modernization with the purchase of Western iron-clads from the West. Similar reforms in Japan proved far more successful, but the parallels remain striking.

Cixi certainly made her share of mistakes. Perhaps the most disastrous was supporting the abortive Boxer Rebellion against the Western powers in 1900. In doing so, and in Cixi’s own words, she had committed “virtually a crime” by bringing thorough defeat and humiliation to China. To the end, Cixi refused to relinquish the power of the monarchy, helping pave the way for the overthrow of imperial rule and the rise of the Chinese Republic in 1912.

Perhaps it is too much to say, despite Chang’s prodigious scholarship, that Cixi “launched modern China”, but she mounted the earliest, and in many ways most radical, campaign to do so.