Legacies of War in Laos

Asia Society Northern California and the Japan Policy Research Institute hosted veteran journalists Karen Coates and Jerry Redfern for a program on November 12 looking at the “secret” U.S. bombing of Laos during the Vietnam War, the unexploded ordinance (UXO) left behind, and its profound impact on everyday life in the country even today. From 1964 to 1973, the U.S. dropped 4 billion bombs on Laos. To this day, the country holds the dubious distinction of being the most heavily bombed neutral country in history.

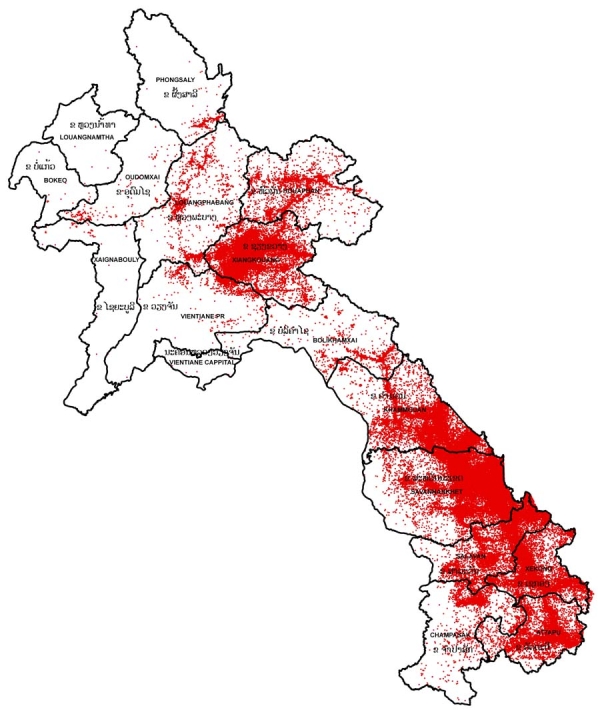

580,000 bombing campaigns and four decades later, a fourth of Laotian territory is littered with UXOs after nearly a third of the bombs failed to detonate on impact. Tens of thousands of Lao civilians have been killed or maimed by “bombies,” as they are called locally, including many children who mistook them, especially the tennis-ball-sized cluster bombs, for toys. Laos remains heavily agricultural, and many farmers have also been killed or injured while working the fields.

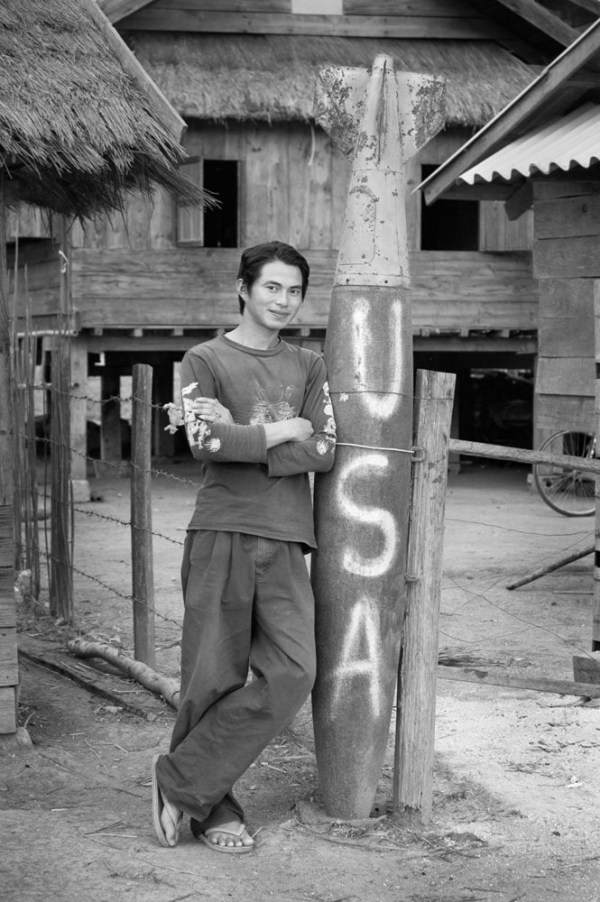

The Lao people have adapted in some surprising ways, transforming shrapnel, shell casings, and unexploded bombs into everything from decorations to boats, spoons, and ladders as well as creating a thriving, but highly dangerous market in scrap metal trade. Scrap is worth about 10 cents a pound and a large shell can bring in $30-40, a crucial income source for many Lao families. Scrap is sent for smelting across the border to Vietnam, where much of it is transformed into rebar used in construction sites across the region: “Laos is rebuilding on American scrap,” Redfern observed. Often the scavengers are young, helping support their families by searching bomb-ridden forests for metal. Children are taught about the deadliness of UXOs through the “bombie song,” which most Lao can recite from memory.

Clean up efforts to rid the country of UXOs are under way, but at a painfully slow pace. The U.S. spent $17 million a day to drop the bombs, but contributed just $61 million between 1993 to 2012 to remove them. At the current rate of spending, it will take several thousand years before Lao soil is bomb-free. Having little choice, “the Lao people live with these numbers and statistics every day of their lives,” said Coates.

Despite their high failure rate and the danger they pose to non-combatants, cluster bombs continue to be used today in conflicts from Lebanon to Iraq and Afghanistan--whose civilians will face the same dangers as seen in Laos for decades to come. The Convention on Cluster Munitions (CCM) was created in 2010 to ban all use of cluster bombs, but the U.S., China, and India (among others) have refused to sign or ratify the treaty.

Coates and Redfern’s reporting and photos are available in the just-published book Eternal Harvest: The Legacy of American Bombs in Laos. Photographs featured in the book are currently on exhibit at Holy Names University in Oakland, California.