"intriguing ... beautiful"

"hypnotic power"

"beautiful and enchanting"

A master of postwar abstraction, Zao Wou-Ki (1920–2013) created a unique pictorial language shaped by diverse influences. Throughout his long career, Zao’s experimentations in oil on canvas, ink on paper, lithography, engraving, and watercolor, allowed each image to evolve from the next, without imposing boundaries. As an artist, he came to inhabit his given name, Wou-Ki, or 無極 “no limits.”

Zao Wou-Ki began his formal artistic training at the age of fifteen at the newly established National Academy of Fine Arts (now China Academy of Art) located in Hangzhou. In 1948 Zao immigrated to Paris and soon took the international art world by storm. Over the course of the next six decades, Zao became a major presence in Europe, America, and Asia, and now stands out as an exemplar of the global scope of modern abstraction.

No Limits: Zao Wou-Ki is the first museum retrospective of the artist’s work in the United States. Drawing together key works from public and private collections in America, Europe, and Asia, this exhibition of Zao’s works illustrates the encounter between Asian aesthetics and international art movements that came to define postwar abstract painting. His artistic practice and innovative methods reveal the dynamic cross-cultural circulation of ideas and images, and the role Zao played in the creation of a modernist aesthetic that was a truly pluralistic phenomenon.

Boon Hui Tan

Vice President for Global Arts & Cultural Programs and Museum Director, Asia Society

Can't see the video? Click here.

No Limits: Zao Wou-Ki is co-organized by Asia Society Museum, New York, and Colby College Museum of Art, Waterville, Maine. The exhibition is cocurated by Dr. Melissa Walt, Research Associate, Colby College; Dr. Ankeney Weitz, Ellerton M. and Edith K. Jetté Professor of Art, Colby College; and Michelle Yun, Senior Curator, Modern and Contemporary Art, Asia Society.

The exhibition is on view at Asia Society Museum from September 9, 2016, through January 8, 2017. The exhibition will be on view at Colby College Museum of Art from February 4 through June 4, 2017.

Purchase the richly illustrated exhibition catalogue online at AsiaStore.

[A friend] said to me: ‘To learn is to create.’ I will use that motto.

The National Academy of Fine Arts, where Zao studied, was China’s most progressive art school. Lin Fengmian, its founding director and one of Zao’s teachers, instituted a curriculum that offered instruction in oil painting, as well as in traditional Chinese painting. Zao’s passion lay in mastering western techniques, but he also had classes in traditional calligraphy and ink painting. The still lifes, landscapes, and portraits of this early period drew upon the variety of reproductions of European artworks that he found in western books, Japanese periodicals, and American magazines including Life, Harper’s Bazaar, and Vogue. Zao collected and methodically catalogued clippings of works by Cézanne, Chagall, Matisse, Klee, and Modigliani, among others. Zao graduated from the Academy in 1941 and was immediately appointed assistant professor, a position he held until 1947. During these years in China he embarked on a course of visual “research.” Paintings in this section illustrate Zao’s daring experiments with composition and techniques that included sources as diverse as modern European painting, Chinese landscape painting, and “primitive” motifs from Han-dynasty tomb rubbings. After arriving in Paris, Zao continued his experiments with materials and subject matter emboldened by the new world in which he found himself.

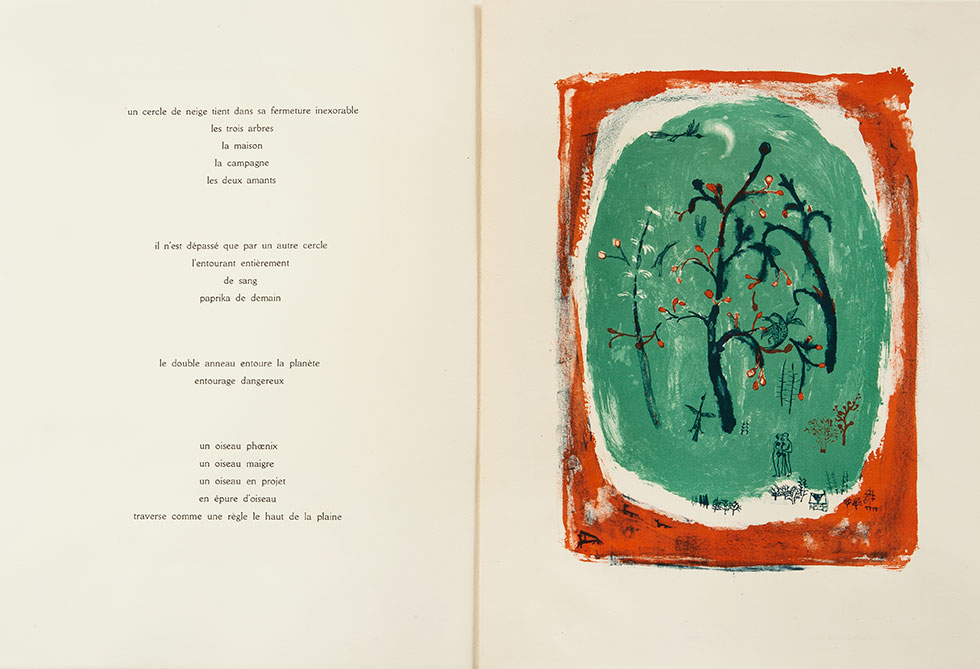

Lecture par Henri Michaux de huit lithographies de Zao Wou Ki (Reading by Henri Michaux of eight lithographs by Zao Wou-Ki), 1950. Eight lithographs. Page: 17¼ × 12 7⁄8 in. (43.8 × 32.7 cm). External portfolio (closed): 17 3⁄8 × 13 1⁄8 × ¾ in. (44.1 × 33.3 × 1.9 cm). Edition 16 of 90. Book by Henri Michaux. Éditions Euros et Robert J. Godet, Paris. Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Columbia University Libraries, New York, Book Arts Collection NC350.Z17 1950 M58. ©Zao Wou-Ki/ProLitteris, Zurich. Photography courtesy Columbia University Libraries

Zao’s interest in lithography dates to 1949. That year, he visited the workshop of the master printmaker Edmond Desjobert, and created a suite of eight prints that caught the attention of the Belgian avant-garde writer and artist Henri Michaux. Zao’s experiment inspired Michaux to pen a series of poems that became Lecture, Zao’s first collaborative artist book, and also marks the beginning of a lifelong friendship between the two artists. The eight lithographs illustrate Zao’s early trials with a new process; in them he employed traditional ink painting techniques, which resulted in a washy, expressionistic effect. Zao drew from his previous sketches for the subjects and compositions of these images, filling them with the symbols and motifs that comprised his visual vocabulary. Mastery of lithographic printmaking opened new arenas for Zao to learn and to create.

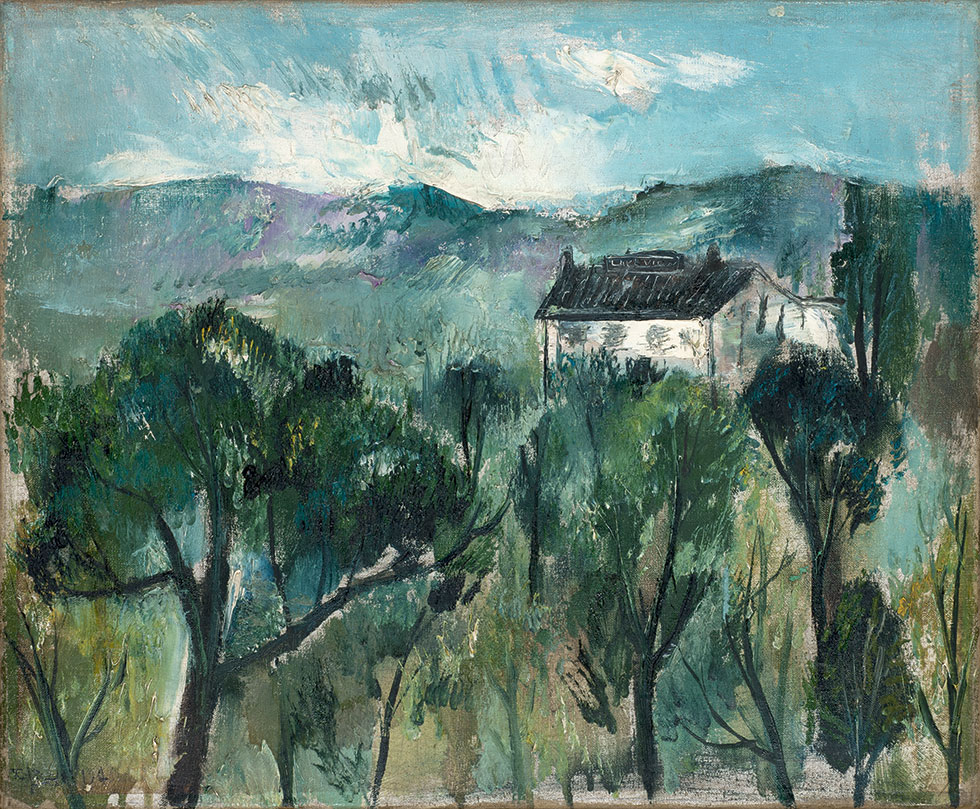

Paysage à Hangzhou (Landscape in Hangzhou), 1946. Oil on canvas. 15 × 18 1⁄8 in. (38 × 46 cm). Private collection, Switzerland. ©Zao Wou-Ki/ProLitteris, Zurich. Photography by Antoine Mercier

The landscape surrounding Hangzhou is renowned for its beauty and has been a compelling subject for artists and writers through the centuries. This early oil painting is a tribute to both Zao’s connection to Hangzhou and to the French painter Paul Cézanne, whom Zao greatly admired. This bucolic painting evokes Cézanne’s own late landscapes depicting Aix-en-Provence in its rich palette of blues and greens, and energetic brushwork. Zao also employs Cézanne’s technique of developing forms through color, rather than through line, one of the fundamental principles that informed Zao’s mature abstractions. Of his early influences, Zao noted in 1979: “Picasso taught me to draw like Picasso. But Cézanne taught me to look at Chinese nature . . . [he] helped me to find myself, to become a Chinese painter again.” But in 1946, Cézanne was just one of the many models and styles from which he found inspiration.

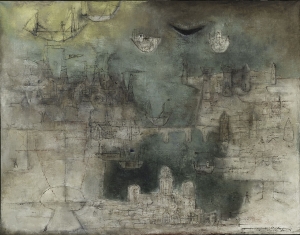

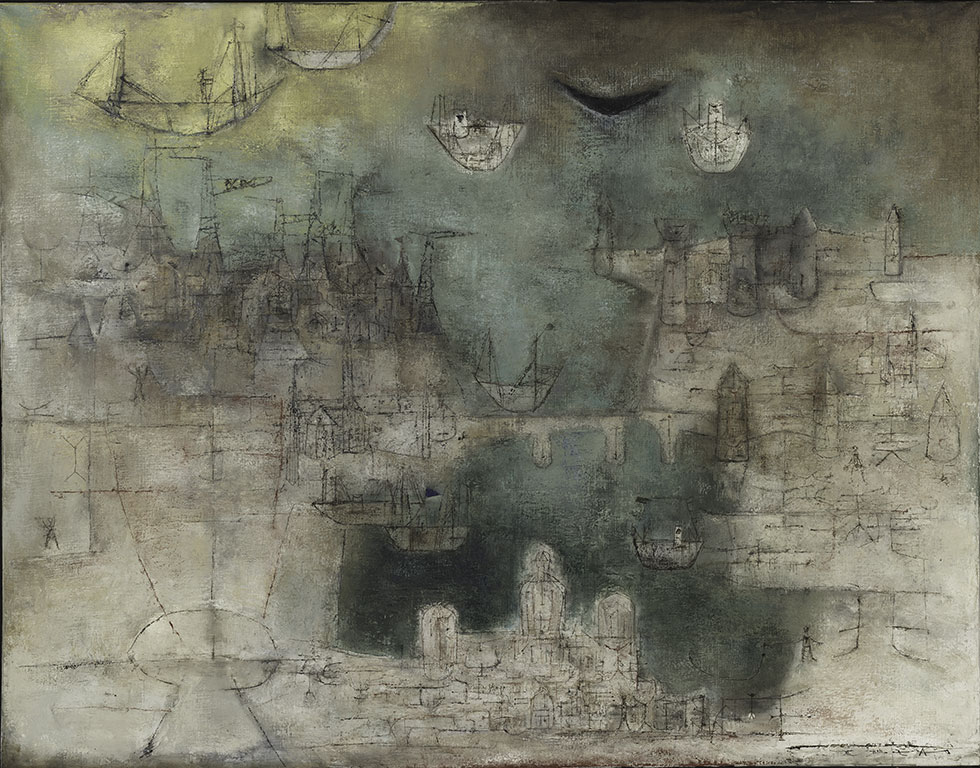

Lune noire (Black moon), 1953. Oil on canvas. 45 × 57 5⁄8 in. (114.3 × 146.4 cm). Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Charles Zadok / Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University. ©Zao Wou-Ki/ProLitteris, Zurich. Photography courtesy of Herbert F. Johnson Museum of Art, Cornell University

This painting is significant as an index of Zao’s motifs up to this point and as an indicator of what would shortly follow in his breakthrough period in the mid-1950s. Paul Klee, like Cézanne, was a significant source of inspiration for the young painter, and his influence left an indelible mark on Zao’s work. Of Klee, Zao noted: “Klee opened up the path that led me to look at nature in my own way.” Klee’s influence is apparent in the palette of Lune Noire, as well as in his use of signs and symbols, including boats, buildings, and other architectural structures drawn from his travel sketchbooks, to create a dense and sometimes almost indecipherable composition.

. . . if the influence of Paris is undeniable in my complete artistic development, I also must say that I have gradually rediscovered China, to the extent that my deepest personality asserted itself. . . Paradoxically, perhaps, it is to Paris that I owe this return to my deepest roots.

By the time Zao Wou-Ki made this statement in 1961, he had settled in Paris and was in the middle of a prolific and transformative period. The artist’s early work had been steeped in the conventions of western modernism, but from 1953 until the mid-1960s, he mined Chinese cultural forms and ideas for inspiration. Zao introduced calligraphic elements first influenced by writing engraved on Shang-dynasty bronzes and oracle bones, and later derived from the broad brush strokes of grass and standard script characters. From this starting point, his artistic language matured into a unique voice that synthesized multiple formal vocabularies and visual idioms.

Hommage à Chu Yun—05.05.55 (Homage to Chu Yun—05.05.55), 1955. Oil on canvas. 76 3⁄4 × 51 1⁄8 in. (195 × 130 cm). Private collection, Switzerland. ©Zao Wou-Ki/ProLitteris, Zurich. Photography by Dennis Bouchard

By the mid-1950s, Chinese cultural traditions came to have a greater influence on the formal and conceptual aspects of Zao’s painting. Chu Yun (also known as Qu Yuan; 340–278 BCE) is a cultural hero known for his loyal service to the King of Chu during the Warring States period (403–221 BCE) and for the collection of lyrical poetry he authored. Political intrigue led to Chu’s being sent into exile where, in despair, he committed suicide by drowning. Every year, Chu’s life and patriotism is celebrated during the Dragon Boat Festival, whose rituals Zao’s family observed each year. In this homage, Zao chose a deep blue palette to which he added Chinese characters and character-like forms in an abstracted tribute to the ancient poet and his literary legacy.

Mistral, 1957. Oil on canvas. 51 1⁄8 × 76 5⁄8 in. (129.9 × 194.6 cm). Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, 59.1545. ©Zao Wou-Ki/ProLitteris, Zurich. Photography © Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Nature was always a source of inspiration for Zao, and his turn toward abstraction coincided with his desire to give visual form to forces of nature that could be felt but not seen. The mistral is a cold, northwesterly wind that blows through the South of France and into the Mediterranean Sea in the late winter and spring. Zao’s dark rendition of this natural phenomenon draws dramatically from the violent and dashing brushstrokes of Chinese grass script. His calligraphic strokes simultaneously create a sense of depth and evoke landscape elements. In the dark lines of the upper left quadrant of the painting, one can almost discern a large tree blown horizontal by the wind and the Chinese characters for “big wind” 大風.

I like people to be able to stroll in my works as I do when creating them.

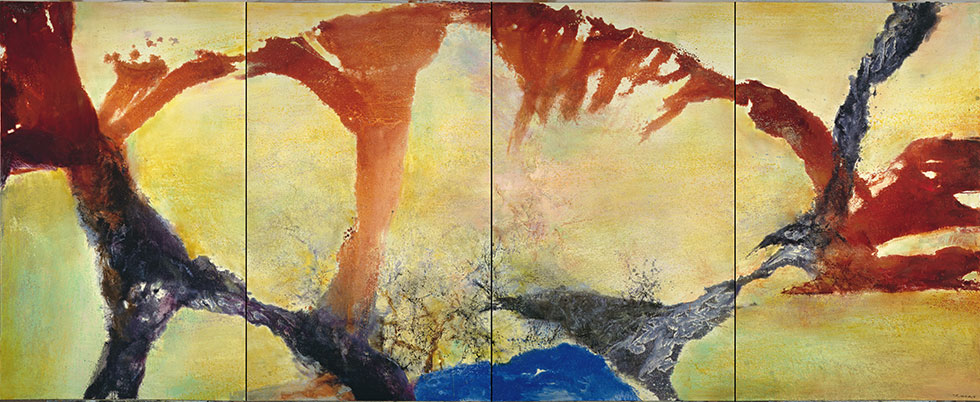

Zao came to this realization in 1967, as he approached a new phase of abstraction that would continue until the artist’s death in 2013 at the age of ninety-three. These ambitious works are meditations on the artist’s inner life and evoke expansive landscapes and traditional scroll paintings on a grand scale. What distinguishes Zao’s abstractions from those of his peers is the sensibility of ink painting expressed through the bold gestural marks in his vibrant oils on canvas. His return to ink painting on paper in the early 1970s coincided with the declining health of his wife May. Unable to spend the long hours in his studio that oil painting demanded, Zao took satisfaction in putting brush and ink to paper, and from that point on included ink painting as part of his professional practice.

Following the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976, more opportunities arose for artistic exchanges with China, beginning with the artist’s solo exhibition at the National Art Museum of China in Beijing in 1983, and followed by the 1985 invitation to teach at the China Academy of Art, his alma mater. Zao’s identity as a global artist, one who was able to transcend physical and cultural boundaries through his trailblazing vision, was secured.

15.04.77, 1977. Oil on canvas. 78 3⁄4 × 63 3⁄4 in. (200 × 162 cm). Private collection, Taiwan. ©Zao Wou-Ki/ProLitteris, Zurich. Rights Reserved

Following the death of his second wife in 1972, Zao returned to China to visit his family for the first time since 1948. After this brief hiatus, Zao returned to oil painting in earnest, but the influence of his engagement with ink painting is clear in many of the works of this period. Here, oil paint takes on the characteristics of ink and Zao even exploits a technique of Chinese calligraphy known as “flying white” (feibai), in which the hairs of the brush separate and leave unpainted areas of the surface visible. Zao’s use of this calligraphic motif conflates the act of painting with the pictorial structure of the work, something he had in common with other postwar abstract painters, such as his American contemporary Franz Kline. This work was formerly in the collection of the architect I.M. Pei, a fellow expatriate from Shanghai and longtime friend and collaborator of Zao.

Hommage à Henri Matisse I—02.02.86 (Homage to Henri Matisse I—02.02.86), 1986. Oil on canvas. 63 3⁄4 × 51 1⁄8 in. (162 × 130 cm). Private collection, Switzerland. ©Zao Wou-Ki/ProLitteris, Zurich. Photography by Dennis Bouchard

Henri Matisse was a lifelong influence on Zao’s work. As early as 1943 the French master’s influence can be seen works like Zao’s Untitled (Girl with Flower). Hommage à Henri Matisse I-02.02.86 was directly inspired by Matisse’s 1914 painting Porte-fenêtre à Collioure. In an interview with La Nouvel Observateur in 1984, Zao proclaimed Matisse’s work “perfect painting.” The outward simplicity of Matisse’s composition belies a depth that Zao found “diabolical” and which inspired this tribute.

Sans titre (Untitled),1980. Brush and ink on paper. 26 1⁄2 × 27 1⁄8 in. (67.3 × 69 cm). The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of Constance B. Cartwright, 1980. ©Zao Wou-Ki/ProLitteris, Zurich. Photography © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA / Art Resource, NY

Zao’s grandfather tempered his modern education with classical Chinese learning including lessons in painting and calligraphy. As a result, ink painting had always come easily to Zao and he found little challenge in it. However, in the early 1970s ink painting assumed a new place of importance in Zao’s artistic practice. Unsure of his new brush and ink abstractions, Zao sought the advice of his friend Henri Michaux, who had been using ink to create his own drawings since the mid-1950s. Michaux urged Zao to continue these experiments. The fluid sensibility Zao achieved through his re-engagement with ink painting again transformed his approach to oil painting.

Critical support for No Limits: Zao Wou-Ki is provided by The Henry Luce Foundation and the Julis-Rabinowitz Family Art Initiative.

Major support is provided by Betsy and Edward Cohen / Areté Foundation, Fondation Jean-François and Marie-Laure de Clermont-Tonnerre, and an anonymous donor.

Additional support is provided by Michel David-Weill, Michel David-Weill Foundation; the E. Rhodes and Leona B. Carpenter Foundation; Marina Kellen French and the Anna-Maria and Stephen Kellen Foundation; Cynthia Hazen Polsky and Leon Polsky; and Karen Y. Wang and Kevin J. Masterson.

Support is provided by Kaifeng Foundation; China Merchants Bank, New York Branch; and Patricia P. Tang.

Research, support, and collaboration were provided by Fondation Zao Wou-Ki. We gratefully acknowledge the professional services provided by Christie’s.

We would like to acknowledge Mr. Pan Gongkai, an enthusiastic champion of the exhibition, for whose support we are grateful.

SPECIAL EVENT

No Limits: Zao Wou-Ki Opening Celebration

Thursday, September 8

Please join us for a celebration of the Asia Society Museum fall 2016 exhibition No Limits: Zao Wou-Ki. This is an exclusive opportunity to view the exhibition before it opens to the public, with musical entertainment and fusion cuisine that bridges the East and West.

MEMBERS-ONLY LECTURE

Why Zao? Why Now?

Monday, September 12 • 6:30 pm

Join guest curator of No Limits: Zao Wou-Ki Melissa Walt for an in-depth talk exploring the diverse influences of Zao Wou-Ki’s singular artistic vision, and his role as a pioneering figure in global abstraction.

PERFORMANCE/ASIALIVE

Encounters: A musical exploration by Susie Ibarra, Samita Sinha, and Jen Shyu

Saturday, October 1• 8:00 pm

FILM

The China Onscreen Biennial

Thursday-Sunday, November 3-6• 8:00 pm

SYMPOSIUM

Asian Abstractions/Global Contexts

Friday, November 18

Presented in conjunction with the exhibition No Limits: Zao Wou-Ki and co-organized with Colby College Museum of Art.

All programs are subject to change. For tickets and the most up-to-date schedule information, visit AsiaSociety.org/NYC or call the box office at 212-517-ASIA (2742) Monday through Friday, 1:00-5:00 pm.