This small, focused exhibition uses one of the rare prints of Ma Junliang's map of the world Jingban tianwen quantu as a starting point to consider the interaction between China and Europe during the eighteenth century. The map offers viewers a Chinese perspective about power and the nature of the world with China at the center. The exhibition also includes Chinese eighteenth-century artworks that appropriate and reinterpret European images and techniques.

This exhibition is part of Asia Society Museum’s ongoing In Focus series, which invites viewers to take an in-depth look at a single, significant work of art.

The eighteenth century in Europe was a period of continued exploration and discovery. While European leaders including Louis XIV (personally reigned 1661–1715), Peter the Great (reigned 1682–1725), Catherine the Great (reigned 1762–96), and Napoleon Bonaparte (1769–1821) expanded their empires, in China the Kangxi emperor (reigned 1662–1722), the Yongzhen emperor (reigned 1723–35), and the Qianlong emperor (reigned 1736–95) brought the Qing dynasty to the pinnacle of its geographical expansion. In the eighteenth century, Qing domination included large portions of Central Asia and parts of the south, including Burma (Myanmar) and Annam (Vietnam).

European and Chinese engagement continued to increase after having already reached historic levels by the close of the sixteenth century thanks to exchanges between European Jesuits and China’s ruling elites. Geographic information gathered in the course of expansion and exploration, as well as mathematical, scientific, and medical research, was exchanged between east and west.

This interchange, combined with cross-cultural admiration, had considerable impact on the arts and crafts across the globe. For example, European craftsmen at Dresden working under enthusiastic support from Augustus the Strong (1670–1733) strove to discover China’s secret to producing true porcelain, finally succeeding by the first decade of the eighteenth century. Meanwhile, artisans working with Jesuits at the newly established Qing imperial glass workshops in Beijing strove to create the finest glass ever produced in China.

This exhibition is part of Asia Society Museum’s ongoing In Focus series, which invites viewers to take an in-depth look at a single, significant work of art.

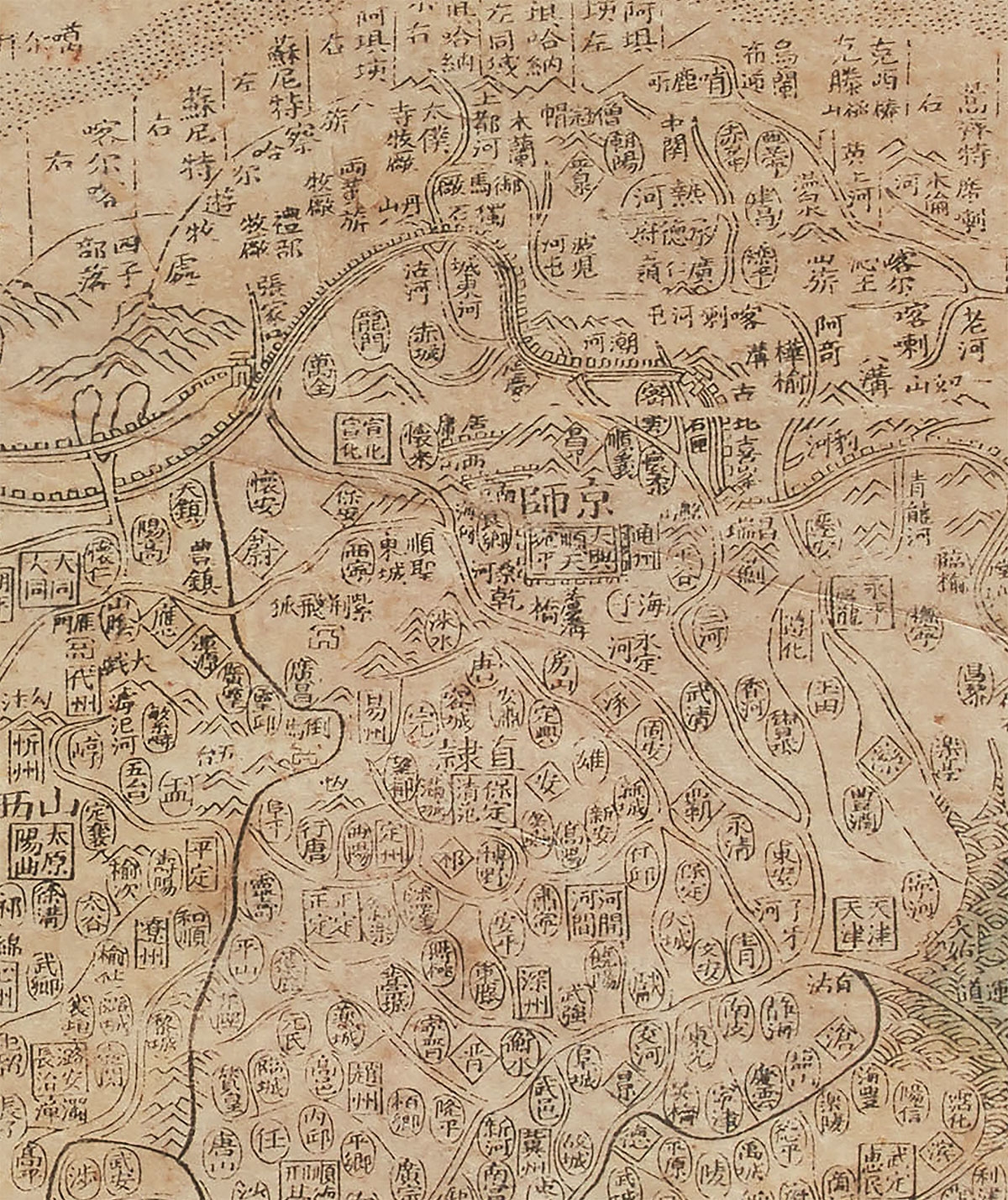

The rare woodblock print map datable from the 1780s or early 1790s titled the Capital Edition of the Complete Map (of the World Based on) Astronomy (Jingban tianwen quantu) is a testimony to the sharing of Chinese and European geographic knowledge. It is the work of the scholar Ma Junliang, a Qing dynasty civil servant, author, and, most famously, mapmaker. Ma came from Zhejiang province on the southeast coast of China and published the Jingban tianwen quantu when serving under the Qianlong emperor.

Ma’s map belongs to a Chinese genre called complete maps of all under heaven (tianxia quantu) that were the most commonly produced maps of the world between the late seventeenth and mid-nineteenth centuries in China. However, unlike previous maps in this genre, Ma’s map includes three very different maps on one sheet and represents a combination of contemporary eastern and western global geographic understanding. The large map of the Qing empire that fills the lower half of the composition is an updated version of one created by Huang Zongxi in 1673, which had been modeled after Ming dynasty mapmaker Liang Zhou’s Universal Map of the Myriad Countries of the World, with Traces of Human Events, Past and Present (Qiankun wanguo quantu gujin renwu shiji) from circa 1600. Ma’s map of the Qing dynasty empire details mountain ranges, rivers, lakes, and deserts. Large bodies of water are marked by repeating ripple patterns, mountains are indicated by chevron-shaped peaks, and deserts are represented by multiple small dots. China’s provinces are separated with bold outlines and the levels of smaller administrative establishments are designated by rectangles, ovals, and diamonds. The Great Wall is rendered using a battlement (square wave) pattern. Above this large map, Ma provided the name of each province along with the number of administrative divisions within each. The map includes areas subjugated during Qing rule including Mongolia’s forty- nine banners, Hami (Xinjiang), and others.

Above the large map are maps of the eastern hemisphere and western hemisphere. The map at the top left and the explanatory text to its left come from General Map of the Four Seas (Sihai zong tu), a circa 1730 map by Chen Lunjiong. Chen likely derived his map, which outlines the Eurasian continent and Africa, from both a European source given to him by the Yongzhen emperor and his own maritime experience and research. The upper right is Ma’s appropriation of the 1602 World Map (mappamundi), the first map of the world known in China and the product of a collaboration between Italian Jesuit Matteo Ricci (1552–1610) and Chinese scholars. Though largely based upon European models, like Chinese maps it is densely annotated and has China and the Pacific Ocean at the center. Ma’s version shows the world as spherical with more water than land, but it compresses and simplifies Ricci’s map. Unlike the original, which shows five continents, Ma’s only depicts Asia to the left, South America to the right, and Antarctica below.

The Kangxi Emperor began the Qing dynasty’s imperial engagement with western learning. He accepted scientific implements, ingenious gadgets, and works of decorative art offered as presents by European rulers like Louis XIV. He also engaged learned European Jesuits at court to advise him as well as to collaborate with Chinese officials and others serving him. European envoys hoped to entice the Chinese into trade relations, while the primary goal of Jesuit priests was the conversion of the Chinese to Catholicism following the principles of “assimilation and acculturation,” postulated by Italian Jesuit Alessandro Valignano (1539–1606). The Qing emperors remained wary of trade relations that would benefit rulers they believed should be subservient to China and also were not convinced that they should dispose of China’s other religions in favor of Christianity. Still, they were more than pleased to learn from and exploit foreign scientific knowledge, and the Jesuits, for their part, were able to learn from their Chinese counterparts at court.

Kangxi, having learned of the French Royal Academy of Science, established fourteen imperial workshops including a glass works, an armory, a clock manufacturer, precious metal and stone works, a lacquer and wood works, an enamel workshop, and a map workshop. He placed several Jesuits in supervisory roles in the workshops. Although the exact extent of the Jesuit influence on the Qing Emperors and their circles is difficult to determine, it is clear that they played a role in a range of areas, from the production of weapons and numerous mechanical devices; explorations in astronomy, mapmaking, and medicine; diplomatic efforts; and providing input into the artistic life of the court. The missionaries were careful to adapt their expertise to Chinese practices and values and to not contradict or impose their own cultural preferences. All the Jesuits residing at the Qing courts were highly skilled individuals and many of them excelled in several domains. For example, Joachim Bouvet (1636–1730) was a historian, mathematician, and geometrician and Jean-François Gerbillon (1645–1707) was a geographer and chronicler. Both were appointed at the Kangxi court and maintained strong contact with the Emperor.

Yet, the standing of the Jesuits at the Qing court shifted during the second half of the eighteenth century when they were relegated to a position of mere foreign advisors and experts, which in the court hierarchy put them below the Emperor’s minions. Still, the Jesuit mission in China remained strong since the Qianlong emperor continued to value their expertise in arts and architecture. Many works created in the Imperial workshops during Qianlong’s reign exhibit characteristics that reveal a delight in shared eastern and western skills and knowledge. Glass objects are among the exceptional works made by skilled Chinese craftsmen during this time using both eastern and western artistry. Though glass has been in China since at least the fifth century BCE and the earliest Chinese-made vessels date to the Western Han period (206 BCE–25 CE), glass never developed there to the same extent as jade, bronze, and porcelain. However, interest in imported glass, which was considered exotic and valuable, had ebbed and owed for many centuries. Western glass received renewed interest around 1595 when Matteo Ricci presented two glass prisms to the Emperor Wanli’s (1563–1620) officials. Later, the Kangxi emperor decided to satisfy the demands of his court for higher quality glass objects by seeking out missionaries to teach Chinese artisans how to make European-style glass. The Jesuits, needing optical glass for their scientific instruments, enthusiastically responded to this initiative, and an imperial glass workshop was inaugurated in 1696. German Jesuit Kilian Stumpf (1655–1720), a highly skilled glassmaker, was assigned to head the workshop. Stumpf’s successors, French Jesuits Gabriel-Léonard de Brossard (1703–58) and possibly Pierre d’Incarville (1706–57) taught Chinese craftsmen how to make two highly coveted kinds of glass: overlay glass, which was used to create the engraved glass vase pictured here, and Venetian aventurine or golden star (jinxing) glass. Another European technology, diamond-point engraving, was introduced about the same time in order to engrave ornamentation and to properly mark workshop production.

Glass was just one of the mediums used to produce the large quantity of exquisite and enormously popular snuff bottles created in the imperial workshops. Both snuff and snuff boxes became popular gifts from Vatican and European countries to the Qing court through the eighteenth century. To maintain its aroma and proper consistency, snuff has to be kept contained and dry. European-style snuff boxes, which were often gifted with snuff, were ill-suited to the humid Chinese climate. Initially, the Chinese used cylindrical medicine bottles to hold snuff, but soon the Kangxi Emperor’s workshops were producing cunning, multi-shaped bottles with pretty stoppers and attached ivory spoons for dispensing snuff.

The Qianlong Emperor particularly appreciated the artfulness of the miniature containers and, like his father and grandfather, he presented the tiny bottles as gifts to honored officials and foreign dignitaries. Court officials and others exchanged lovely snuff bottles as gifts, as did members of the Chinese elite beyond the palace walls. Some Qianlong-era snuff containers are embellished with exotic images of Europeans they may have thought seemed especially well-suited for this imported substance. The works included in this exhibition are copper-bodied painted enamelware with the enamel design painted directly onto the metal surface. The technique, which originated in fifteenth-century Flanders, was incorporated into palace workshops under Kangxi. Two craftsmen from Canton, Pan Qun and Yang Shizhang, were enlisted by the workshop in the 1710s and were joined in 1719 by a French Jesuit supervisor, Jean-Baptiste Gravereau (born 1690).

Today, through maps like The Capital Edition of the Complete Map (of the World based on) Astronomy and decorative objects like snuff bottles and glass vessels, we are able to catch a glimpse into Europe and European learning as seen through eighteenth-century Chinese eyes. Much of what they saw was cunning and delightfully exotic. Far from the Central Kingdom (Zhongguo, the Chinese name for China) there were strange lands as represented in the example in this exhibition and captured in the caricature of oddly dressed aristocrats accompanied by child-servant boys barely clad to conceal their nudity. This Chinese view provides an engaging counterpoint to that frequently provided on Europe’s chinoiserie, which is often filled with mandarins and ladies in exotic robes and headdresses strolling through fanciful landscapes with pavilions.

Curtis, Emily Byrne . Glass Exchange Between Europe and China, 1550-1800: Diplomatic, Mercantile, and Technological Interactions. Farnham, England; Burlington, VT: Ashgate, 2009.

Elman, Benjamin A. On Their Own Terms: Science in China, 1550-1900. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press, 2005.

Emerson, Julie, Jennifer Chen, Mimi Gardner Gates, Porcelain Stories: From China to Europe. Seattle, WA: Seattle Art Museum in association with University of Washington Press, 2000.

Pegg, Richard A. Cartographic Traditions in East Asian Maps. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2014.

Snuff Bottles in the Collection of the National Palace Museum. Taipei: Guoli gugong bowu yuan, 1992.

Website References:

"Complete Map of Astronomy and the Qing Empire." Reading Digital Atlas. Accessed January 31, 2019. http://digitalatlas.asdc.sinica.edu.tw/digitalatlasen/map_detail.jsp?id….

"Jingban tianwen quantu ," Rice Scholarship Home, accessed January 31, 2019, https://scholarship.rice.edu/handle/1911/81426.

Smith, Richard J., "History of the Jingban tianwen quantu." Woodson Research Center - Fondren Library - Rice University, accessed January 31, 2019, https://exhibits.library.rice.edu/exhibits/show/jingban-tianwen-quantu/….

To enjoy Asia Society's free audio guide for A Complete Map of the World: The Eighteenth-century Convergence of China and Europe, just look for the audio icon next to select artworks in the exhibition.

For easier mobile access, listen at Soundcloud.

Support for Asia Society Museum is provided by Asia Society Global Council on Asian Arts and Culture, Asia Society Friends of Asian Arts, Arthur Ross Foundation, Sheryl and Charles R. Kaye Endowment for Contemporary Art Exhibitions, Hazen Polsky Foundation, Mary Griggs Burke Fund, Mary Livingston Griggs and Mary Griggs Burke Foundation, New York State Council on the Arts, and New York City Department of Cultural Affairs.