magazine text block

To say 2020 has been a difficult year would, at this point, be cliche: Across six continents, millions of human beings accustomed to moving about freely have found themselves relegated to their homes, as the invisible coronavirus wound its way around the world like a slow-moving hurricane. Artists were not spared. The pandemic closed museums, galleries, concert halls, theaters, and cinemas across the globe, forcing cultural workers to isolate themselves indoors.

Asia Society has asked a diverse collection of artists and creators to reflect on this theme of isolation: How has the coronavirus — and living under quarantine — affected their lives and work? How will the pandemic shape the future?

Yet if we were to examine cultural isolationism more broadly, we’d find that the pandemic is hardly the only source of blame. In the years before 2020, populist nationalism and xenophobic attitudes fanned by right-wing politicians — and the exploitation of minority communities — steadily accelerated, a trend resulting in a more inward-looking culture.

The author Edward Said once commented about how, within nation states, forces aligning themselves with the orthodox, conservative, and mainstream traditions insist on the idea of a definable “pure” culture — “our culture.” These movements often look back to a historical golden age that may not have existed. There is thus an increasing inability to recognize how any one culture develops in relation to other cultures — that cultures consist not only of the legacies of past historical encounters, but also continue to develop in complex processes of exchange with the cultures of others.

This deterioration in the historical social compact between communities was what prompted my initial proposition for the Asia Society Triennial, a festival of art, ideas, and innovation slated to run from October 27, 2020, through June 27, 2021, in New York City. The artistic projects in the Triennial are an act of resistance against cultural isolationism and often demonstrate the impossibility of a “pure” culture. Artists and artworks are produced within complex webs of association and causality across geography and history. We can thus never be alone.

magazine quote block

magazine text block

Two projects of the Triennial demonstrate this by connecting Asia to the U.S. in unexpected ways.

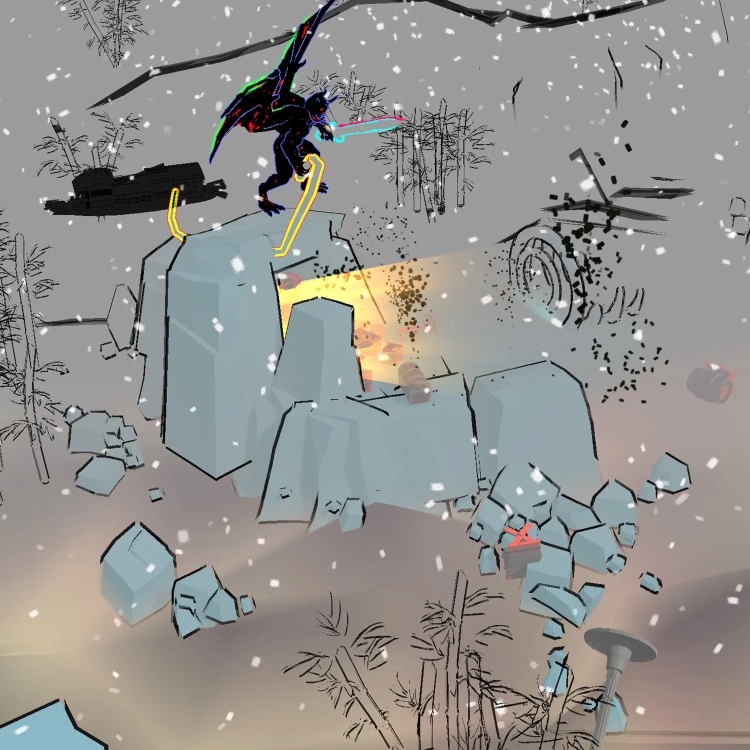

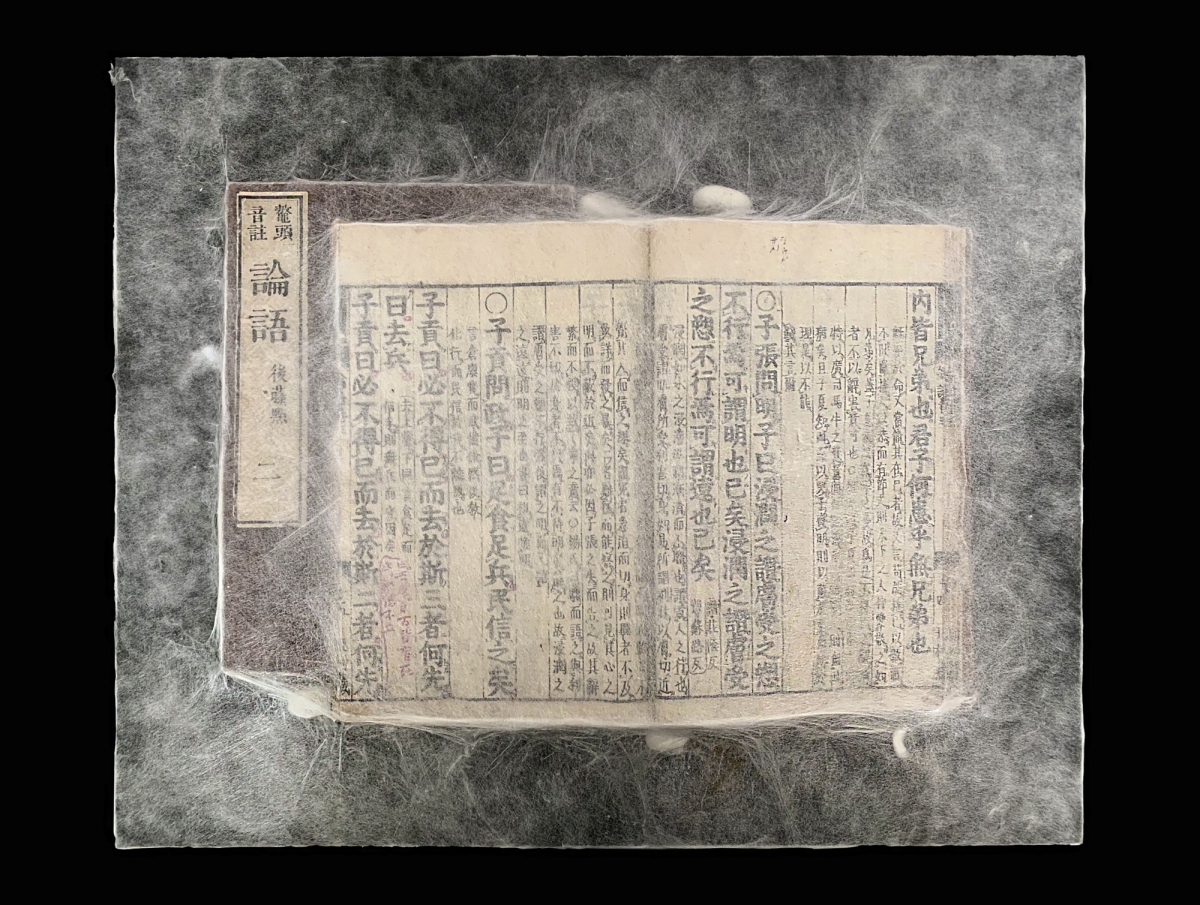

One is We the People: Xu Bing and Sun Xun Respond to the Declaration of Independence, guest curated by Susan L. Beningson, Ph.D. The artists Xu Bing and Sun Xun have created new works to respond to the ideals exemplified in the Declaration — a rare, 19th century copy of which will also be on display — but through the lens of Asia. In her catalogue essay, Beningson writes of how Xu Bing used a copy of The Analects of Confucius, a text that was studied deeply by the founders from the United States, to create a new work made from silkworm thread that comments on the fragility of manifestos such as the Declaration. The younger Sun Xun created a 24-page folding album that borrows from Chinese literati painting traditions to illustrate the fiery dynamics through which new worlds are born or established norms are broken.

The other project comes from Japanese-Australian artists Ken + Julia Yonetani’s Three Wishes installation, featuring three sculptures of an angelic creature. The creature’s wings are from the Zizeeria maha butterfly, hatched from eggs collected as part of a scientific study into the biological impact of the 2011 Fukushima nuclear power disaster. This work was inspired by Walt Disney’s belief in the benefits of atomic energy following World War II and connects the radiation fallout tragedy of Fukushima with its long-term impacts on wildlife and, by implication, human life, to the effusiveness and cheeriness of victorious America’s postwar embrace of a nuclear-powered future.

These two projects express one of the central concerns of the Triennial: that we can never dream alone — or, in fact, act alone. The title of the Triennial, We Do Not Dream Alone, references a line in Yoko Ono’s 1964 seminal publication Grapefruit: “A dream you dream alone may be a dream but a dream two people dream together is a reality.”

It is an argument that art has the potential to counteract our urge to silo during these uncertain times.

Boon Hui Tan is co-curator and former artistic director of the Asia Society Triennial.

Hamra Abbas, Every Color (Detail), 2020. Private Collection, Dubai, UAE. Photograph by Asif Khan.

Hamra Abbas

magazine text block

How did the pandemic change the way artists live, work, and think? We asked eight Asia Society Triennial participants to assess the toll 2020 has taken.

Hamra Abbas

Born in Kuwait City. Lives and works in Boston, and Lahore, Pakistan.

The disruption in our lives due to the strain of this pandemic has been a daunting experience. It has shaken our sense of security and requires a more profound reflection on who we are as people and our responsibilities towards [the] environment and life around us.

Ghiora Aharoni, Thank God for Making Me a Woman, III, 2019. Courtesy of the Artist. Photograph: Ghiora Aharoni Studio ©2019.

Ghiora Aharoni

magazine text block

Ghiora Aharoni

Born in Rehovot, Israel. Lives and works in New York City.

As I’ve had limited access to my studio where I make work, my studio decided to take up full-time residency in my head, so the commute has certainly been shorter. My practice has become more internal … researching, reading, writing, and then sketching new work, all of which I’ve very much enjoyed. Breaking the established rhythm of everyday life has certainly reinforced the preciousness of present time.

I was thinking about the virus being spread through our breath and having to cover our mouths, which is also how we communicate. So I created a face mask with sacred text that speaks to the power of what we spread through our words. I would have liked to produce it, though I knew that all mask manufacturing was dedicated to meeting the public’s needs, so I created it as a digital work instead and shared it on social media, and also as a limited edition work on paper.

Vibha Galhotra

In ... Times, 2020

Original Medium: Performative staged photo-work

Vibha Galhotra

magazine text block

Vibha Galhotra

Born in Chandigarh, India. Lives and works in New Delhi.

I have to say that living in isolation isn’t quite easy. In the beginning, it evoked many highs and lows and helped me reflect on many aspects of my life, not just as an artist, but as a whole. Reading and seeing visuals about the reverse migration of laborers, some of whom were walking up to 400 kilometers to reach their hometowns, the sight of their misery, hunger, mistreatment, and even death in some cases was not only heartbreaking, but induced a sense of loss and led me to question the fragile structures of the society we live in. I have also been attending numerous webinars and Zoom conversations as well as giving virtual presentations about my practice.

The first 45 days of the COVID lockdown in India was a complete shutdown due to which I did not have access to my studio at all. During [this] period I was sketching and making doodles at home. However, since I started going to my studio again, I have been working on some commissioned works which are taking a relatively longer period of time due to the COVID-related precautions of social distancing that my studio staff and I try to maintain.

IN _ _ _ _ TIMES is a series of staged photo works conceived in response to the unimaginable period brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic and is in some respects a continuation of the work I am creating for the Asia Society Triennial. The work exudes a forced sense of social distancing in fear of contracting the virus that has massively changed the world order, questioning the very meaning of what was previously considered normal. Despite being pushed towards surreal boundaries and lifestyles, the gap between our indispensable need for our planet and our uninhibited abuse of the same continues to widen. I wanted to create this series of photo works, then, to express this augmented fear of new-age viruses and the isolation that, while is considered forced in the present times, might just be the new normal of the future.

I don’t know if the pandemic has changed my perspective as an artist, but it definitely has, as a human being, forced me to notice and reflect upon the fragility of our world and the structures we hide behind. The experience is definitely daunting especially for people living in this part of the world with limited means of resources and health care services.

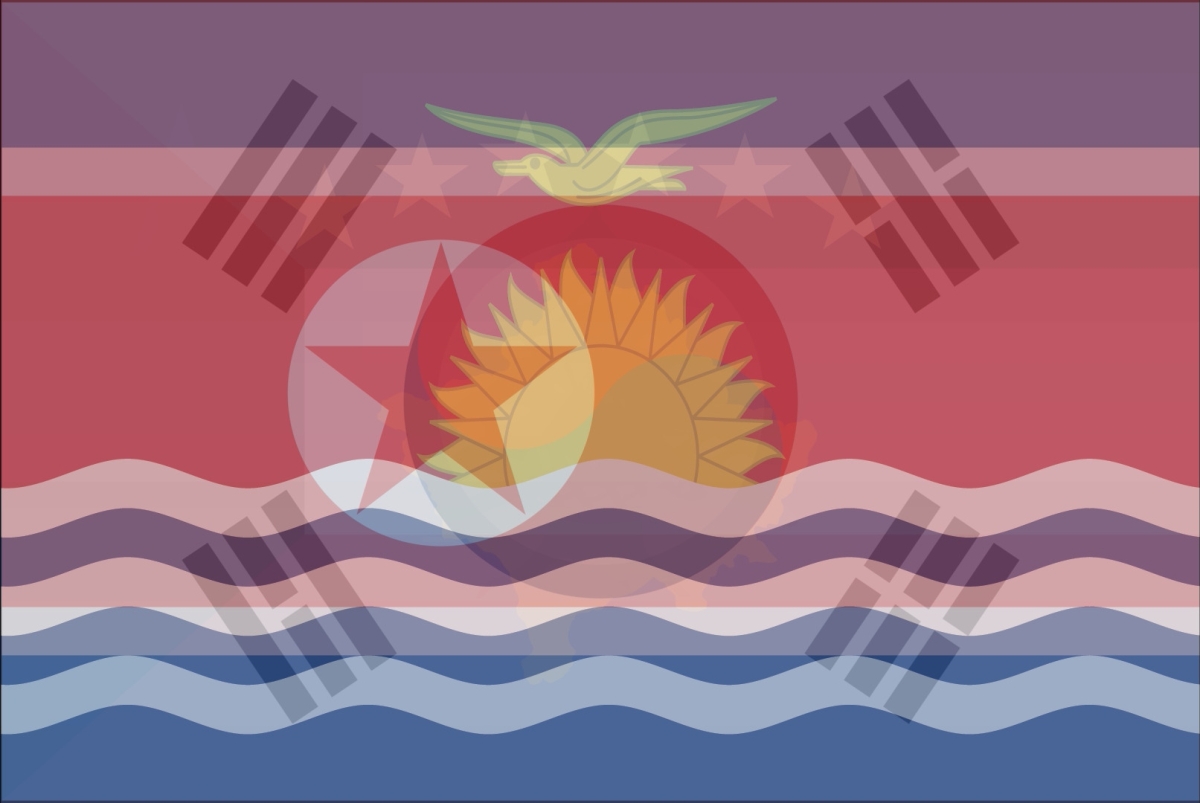

Kimsooja, To Breathe — The Flags, 2012. Courtesy of the Artist. Image Courtesy of the Artist.

Kimsooja

magazine text block

Kimsooja

Born in Daegu, Korea. Lives and works in New York City, Paris, and Seoul, South Korea.

Fortunately, I am used to working remotely from traveling all the time, so it is not a problem working long-distance on large-scale, site-specific projects, albeit with great support from each institution and my studio members who are located in Paris, New York, and Seoul — it is not an issue to not have a physical studio and meetings regularly. And I am not an artist who makes things in the studio unless there is a conceptual necessity. We’ve worked efficiently from each of our homes on different continents. I think installation via video call has been working great, so far.

Installation view of Asia Society Triennial: We Do Not Dream Alone at Asia Society Museum, New York, October 27, 2020 to June 27, 2021. From left to right: Minouk Lim, Hydra, 2015.; L'Homme a la Camera, 2015; Courtesy of the artist and Tina Kim Gallery. Photograph: Bruce M. White, 2020.

Bruce M. White

magazine text block

Minouk Lim

Born in Daejeon, South Korea. Lives and works in Seoul, South Korea.

The pandemic is another war. These days we talk about [the] “new normal” and are getting used to it. Because of [the] “new normal,” things are constantly dissipating, and as an artist, I came to think more about the problems of memory and records. Innovation for change and urgency of the task (vocation) have made us reflect more on the meanings of equality, creation, and extinction of civilization, and broader solidarity for not only human beings but ultimately, for all things.

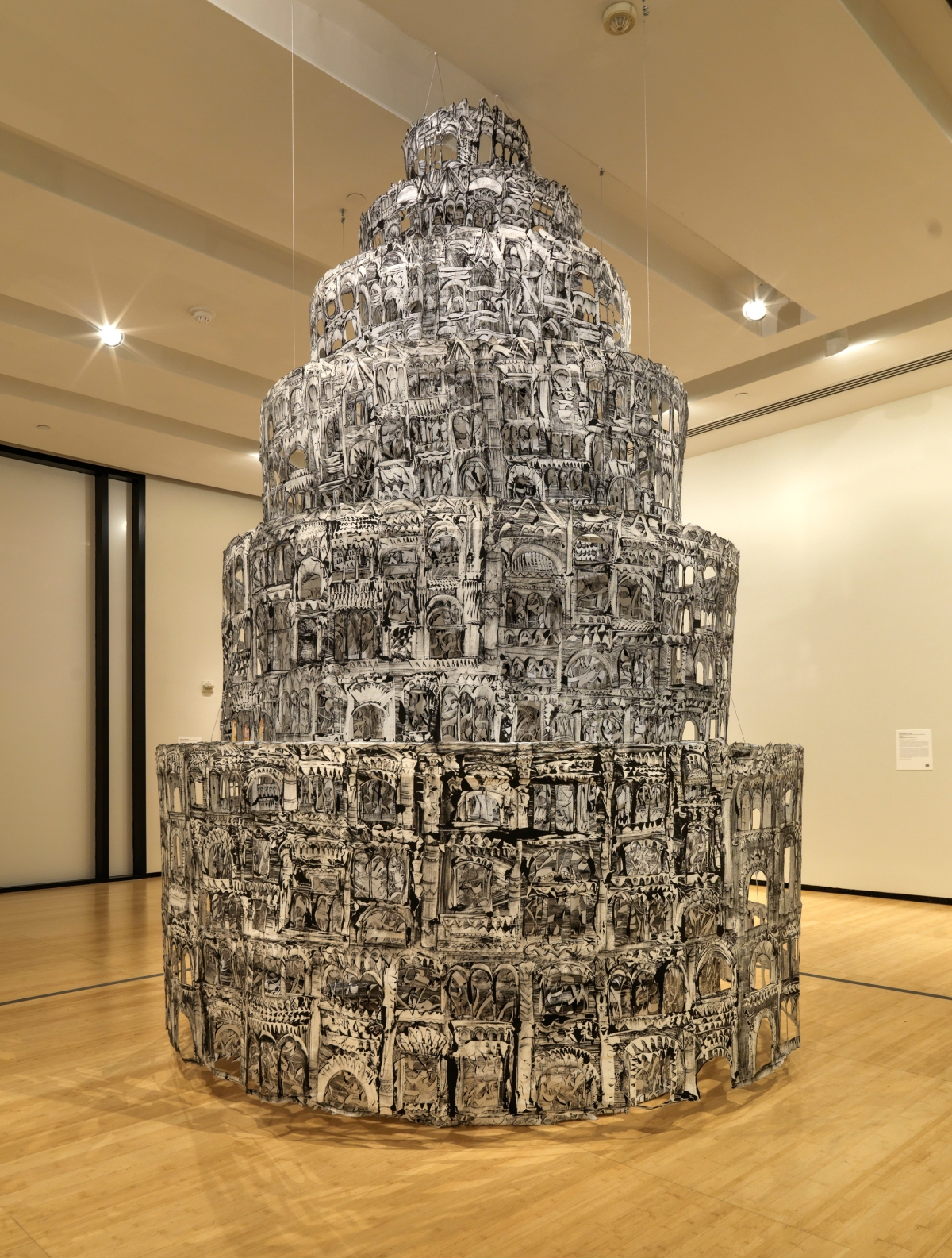

Installation view, Asia Society Triennial: We Do Not Dream Alone, Asia Society Museum, New York, 2020. Kevork Mourad, Seeing Through Babel, 2019, courtesy of the artist. Photograph: Bruce M. White, 2020.

Bruce M. White

magazine text block

Kevork Mourad

Born in Qamishli, Syria. Lives and works in New York City.

At the beginning of the quarantine, when all my upcoming projects were canceled, I decided to reach out to musician friends for musical compositions to which to set short animations inspired by their music. I called it the Quarantine Series, [and it was] done from home before I was able to return to the studio. I would post them on social media to show that we were still alive and active. I also pasted a large piece of paper to my living room wall and worked on it continuously, as well as [in] a small sketchbook, a quarantine diary.

I was fortunate enough to be asked by the Spurlock Museum to create a sculptural piece. I took the idea of being communally isolated in lockdown and created a piece called A World Through Windows for the museum.

More than ever, as artists, we’re responsible for creating work related to social justice and supporting organizations in need. There is more urgency to the artist’s message in these times. Especially now that so many people are in more dire need than ever.

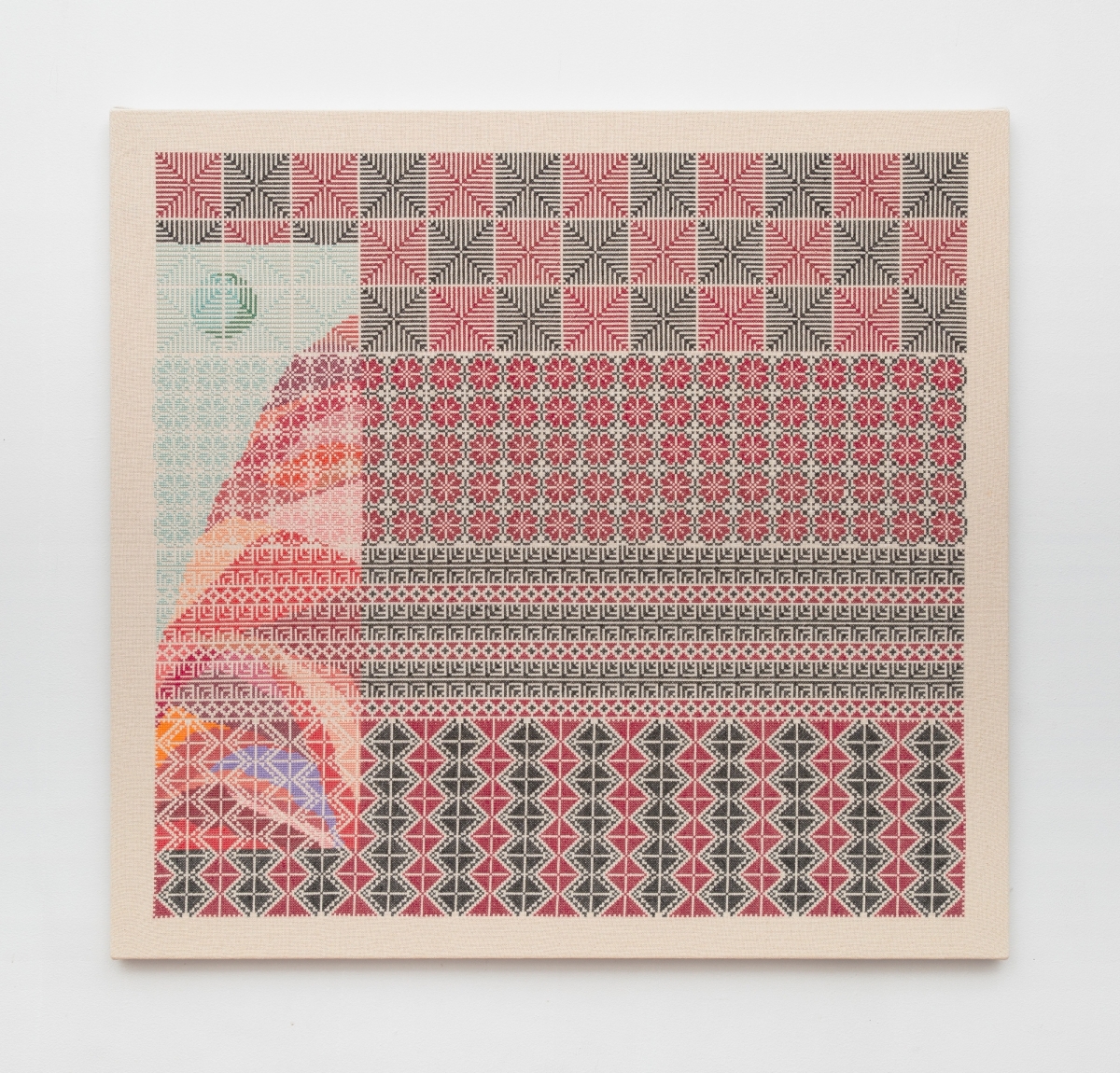

Jordan Nassar, I Am Waiting For You, 2018. Collection of Giora Kaplan. Image courtesy of the artist, Anat Ebgi, and James Cohan, New York.

magazine text block

Jordan Nassar

Born in New York City. Lives and works in New York City.

I think it's safe to say we've all experienced shifts in our perception of life and our priorities — I certainly have. I am feeling more urgency in taking action to solve the many problems of this world — and not just because we want to “solve problems,” but because it's people's lives we're talking about when we say that. I think, especially in politics, we get so wrapped up in concepts and intellectual arguments that it becomes easy to lose sight of real people's actual needs at this very moment, and I think I've been spending a lot of time accessing how to incorporate a variety of forms of activism into my way of life — not necessarily into my artwork specifically, but into my daily life.

Xu Bing, Silkworm Book: The Analects of Confucius, 2019. Courtesy of the artist. Photograph courtesy of Xu Bing studio.

magazine text block

Xu Bing

Born in Chongqing, China. Lives and works in Beijing and New York City.

It came to me that my works from the past are neither personal nor emotional. However, my current practice is so personal and highly relevant to what has happened to my life during the pandemic.

The pandemic makes me reflect on why some art has values while other [art] does not. What are the differences? In my opinion, the art that has values resembles coronavirus in so many ways. If there is something called "contemporary art," it is like an "unknown virus" from outside of the body if we compare the human body to our civilization, lurking inside the biological system, grabbing the blind spot of the existing system, and breaking such a mature and complete system with something that was not available in the past. Its nature is unknown, its origin is undetected, and it has never been classified or categorized by any knowledge from the past.

Then the balance is broken, it has to rely on philosophers, art historians, theorists, art critics, etc., to categorize and analyze these things (artworks), and, as a result, produce new knowledge. While these "unknown viruses" are being studied and understood, they are mutating into conventional viruses (such as influenza) in order to adapt themselves to the environment; they turn into long-term service viruses and do the work of regulating and improving the body’s health at the right time. All are "viruses," the difference is "unknown" or "regular." A healthy body needs the attachment of some "bad" cells to cooperate with the “good” ones. As a group of “bad” cells, contemporary art is acting as a trigger point for the cleansing and reconstruction of human civilization through a seemingly naughty way.