magazine text block

Climate change is one of the biggest crises of our time, and one of its most significant impacts will be on human migration. This is not a new understanding. We have long known that rising sea levels, increasing temperatures, desertification, and worsening natural disasters will force unprecedented population movements. The World Bank and the International Organization for Migration predict that by 2050 hundreds of millions of people will have been displaced due to climate change.

In the world’s poorest and most agriculturally dependent areas, this mass migration is already underway. Of the 71 million people currently displaced globally, roughly one in four has been forced to leave their home due to natural disasters and it is inevitable that more and more people will become migrant laborers as their livelihoods at home are threatened.

Take the case of Indonesia. Every year, millions of Indonesian workers head to plantations, factories, and homes across Asia and the Middle East — many of them driven by failing farms. With a changing climate leading to worsening floods and droughts, agricultural work is becoming increasingly unpredictable. Without a steady income, more and more Indonesian families are turning to risky migrant labor.

Over the past few years, I have been traveling across Asia documenting families impacted by climate migration. In 2018, I went to Indonesia’s East Nusa Tenggara province, where farming families have been struggling with drought. To cope, women migrate to work as maids in Malaysia. While it is a job prone to exploitation and worse, many families told me they feel they have no choice.

With climate change precipitating ever-higher levels of mass migration, experts warn that human trafficking will rise in kind. The most desperate workers will also be the most vulnerable to abuses like forced labor and sexual exploitation. In the absence of serious labor reforms, tragic stories like those from East Nusa Tenggara will become the norm.

This reporting was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

In November 2013, a stranger named Johan Pandi came bearing gifts and promises for the Abuk family, and asked for permission to take 27-year-old Dolfina to work as a maid in Malaysia. With their farm suffering, the family saw it as a crucial opportunity. Dolfina left her two children behind and went with Pandi, who gave her a fake identity card and passport. Here, Dolfina’s suitcase sits inside the family hut.

Xyza Cruz Bacani

The family was so happy with Dolfina’s good fortune that when another recruiter came to their village, they sent her older sister Mariah to work as a maid in Malaysia as well. In March 2016, Dolfina called her mother and said she would soon be returning. Those were the last words they heard from her.

Later that month, the family received a call from an employment agency in Malaysia saying Dolfina had died and her body would be shipped back. They insisted the young woman had died of natural causes and gave no further information. Above, Mikhael Abuk shows a photo of his daughter in her coffin.

Xyza Cruz Bacani

Police officer Ruddy Soik is a member of the human trafficking unit of East Nusa Tenggara. He has been working on human trafficking since 2012. When I met Soik in his home, he showed me his files related to some of these trafficking cases. He was proud to say that in 2018, his unit caught nine traffickers. The file is thick and well organized. It is filled with details and images of victims who left with a promise and came home either dead or abused.

Soik says he is frustrated that human trafficking is still so widespread. The hardest thing for him is changing the mindset of the families about sending away their daughters, but he says it’s hard to blame parents given the circumstances. When the land gets drier, they grow poorer, and the promise of hope in Malaysia seems brighter.

Xyza Cruz Bacani

Sea levels continue to displace those living in low land areas in Indonesia, and agricultural yields have dropped dramatically due to drought and water scarcity, says Renard Siew, an expert on climate change mitigation at the Climate Reality Project. Here, workers in East Nusa Tengarra quarry gravel from a dried-out riverbed.

Xyza Cruz Bacani

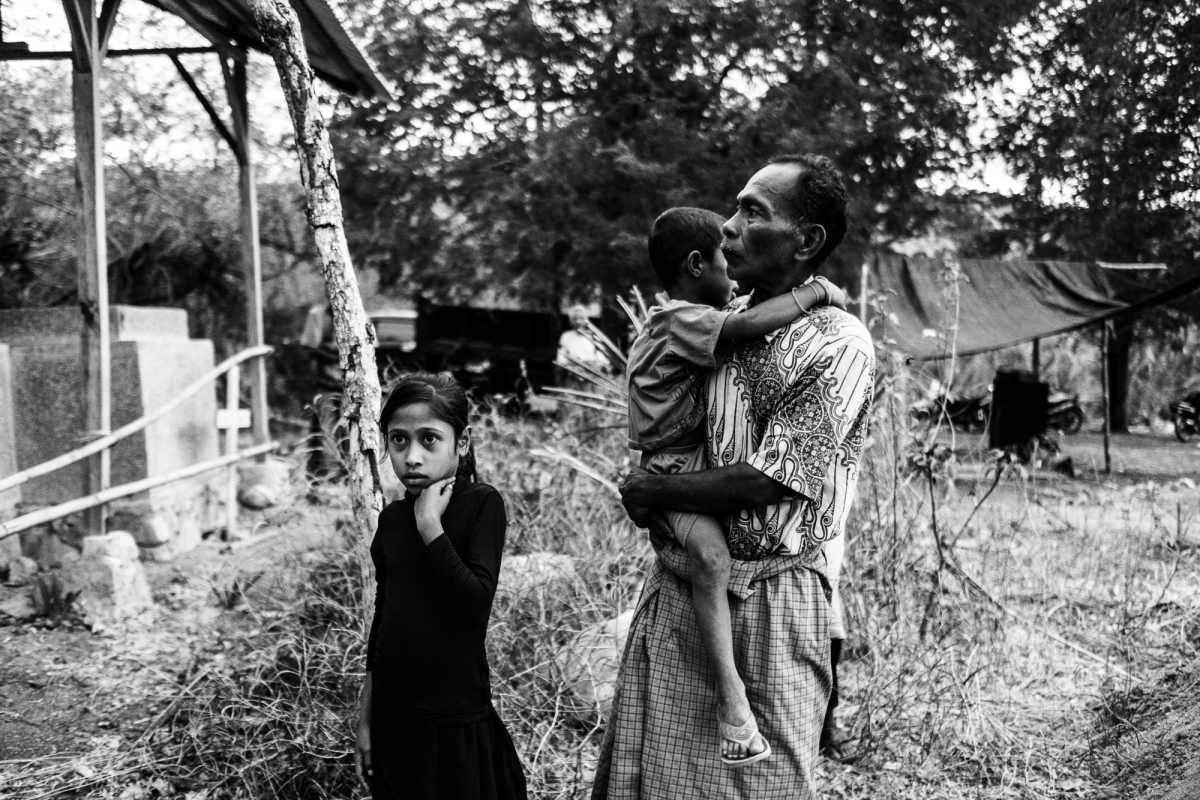

While still trying to cope with the death of his younger daughter, Mikhael received a call from Mariah, who said that she and other undocumented workers were hiding because of raids conducted by Malaysian authorities. Mikhael begged Mariah to come home, but she said she couldn’t risk it without documents or money. She told her family to wait to hear from her. Mikhael is still waiting for the phone call. They have heard nothing more. He can only hope that his remaining daughter will one day come back alive. In the meantime, he and his wife focus on raising their grandchildren.

Xyza Cruz Bacani

Another grieving father is Martin Sauk, a struggling farmer who was promised a better life when his daughter Adelina left for Malaysia. She died after being starved, abused, and forced to sleep outdoors with her employer’s dog in Penang, Malaysia. Her employer was arrested for murder, but the charge was later dropped for unknown reasons.

Xyza Cruz Bacani

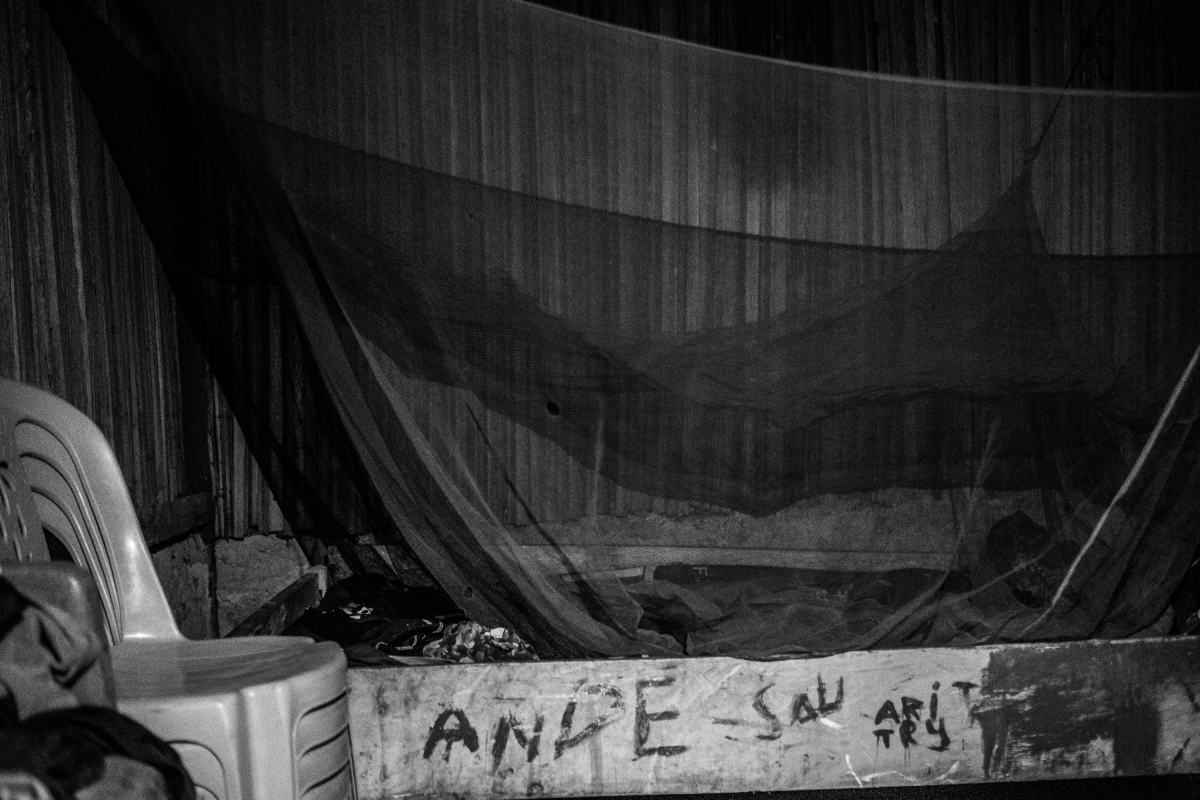

A blurry photo and a bed — that is what’s left of Adelina. Her case is similar to that of many women who left Indonesia hoping for a better life.

Xyza Cruz Bacani

Members of Adelina’s family gather at their home in Ponu, which, like many neighboring villages, has no access to electricity. Though these communities have played the smallest role in causing global warming, they are the hardest hit by it. With the climate changing, millions more people like Adelina, Mariah, and Dolfina will be forced into migration for survival. And unless regulations and enforcement improve — both in the countries people flee, and the ones in which they settle — cases like these will grow tragically ever more common.

Xyza Cruz Bacani