magazine text block

In 2004, India’s Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) was riding high. Led by Atal Bihari Vajpayee, a popular and respected figure who had overseen a growing economy, the party was seeking reelection after a first term generally perceived as successful. The BJP was so confident, in fact, that it called for elections six months early. The party’s campaign slogan — the strident “India Shining” — was meant to remind voters of its sterling stewardship of the economy, and along the campaign trail BJP backers touted the spread of a “feel good” factor under their reign.

None of it worked.

The BJP suffered one of the most surprising upsets in Indian electoral history, with its seat total in parliament dropping from 189 to 144. The Indian National Congress party (INC), which picked up 159 seats on its own and a total of 217 with its allies, would go on to form the next government.

The consumption-fueled optimism of the BJP’s slogan did not resonate with most Indians, and it became a watchword for the BJP’s disconnect with the plight of the common man — struggling with stagnant farm incomes and an unemployment crisis.

Fifteen years later, the ghosts of 2004 loomed large over the 2019 polls.

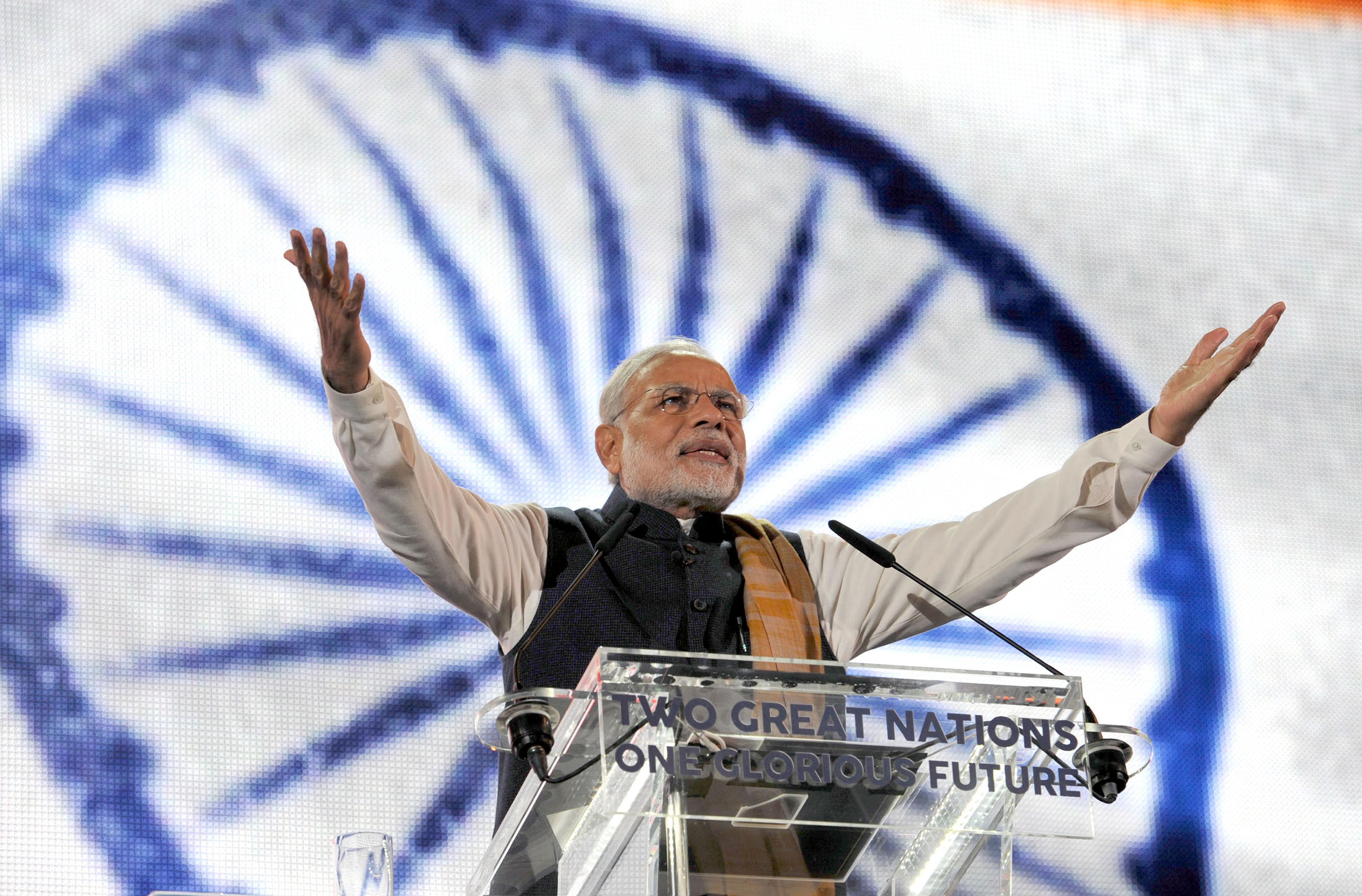

At the start of 2019, India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi and the BJP were gearing up for a reelection campaign to secure a second term in power. Modi’s broad popularity ought to have buoyed the BJP’s confidence, but the currents of Indian politics are famously unpredictable. Few analysts were confident the BJP could secure another majority in parliament on its own when the election took place during a six-week period in April and May.

Growth had plateaued (according to the World Bank, India’s economy grew at 6.98 percent in 2018, a high rate by global standards but the slowest annual rate during Modi’s tenure) and from the perspective of the aam aadmi, or common man, things were not improving quickly enough. For some in rural India, life even seemed to be getting worse. In February 2019, when an employment survey leaked, showing India with the highest unemployment rate in four decades, the BJP panicked.

For a brief moment, the 2019 election seemed to follow the script of 2004. Once again a popular BJP prime minister was running on his economic record, which upon closer inspection seemed less than stellar. The BJP had done poorly in the state assembly elections months earlier. And the moribund Indian National Congress was showing signs of being a worthy opponent again, hammering Modi’s government on the hollowness of its economic record. The stage was set for history to repeat.

Instead, the 2019 election flipped the script, and Modi and the BJP won the biggest majority any single party had managed in decades.

The party’s varied fate in the two elections, one early in the century, the other at the close of its second decade, is emblematic of the evolution of a rising India. The BJP’s 2004 defeat unleashed forces that led to its 2019 victory and have remade the country. At the turn of the century, India was seen as just South Asia’s preeminent player. Today, it has risen to the level of a rising world power.

In that 15-year span, the BJP had changed and the country with it. And in Modi, the party had found a leader who suddenly represented and spoke to the increasingly bold ambitions of the Indian public — for better and for worse.

Mumbai’s Chhatrapati Shivaji Terminus. India’s middle class doubled from 300 million people to 600 million between 2004 and 2012 alone.

Tuul and Bruno Morandi/Alamy

magazine text block

The Pivot

The BJP is a far greater force in Indian politics today than it was in 2004 — it is now a truly national party. In 2004, the BJP had experienced little success outside of India’s Hindi Belt, which severely limited its electoral ceiling. In contrast, at the start of 2019, it controlled more than half of India’s state assemblies and had made significant inroads into southern, eastern, and northeastern India.

It is also a more forceful party, taking on rivals not just in the opposition but in the media, academia, and independent government institutions. Most critically, unlike in 2004, the BJP of today has fully embraced its Hindu nationalist roots, openly touting a Hindu vision of India in its campaigns and attacking the defenders of India’s secular character.

Ironically, the electoral defeat of 2004 may have led to this right turn. Vajpayee was seldom linked with the Hindu right-wing base of his party and took pains to make the BJP appear more inclusive. After the BJP’s defeat in 2004, a major Indian editor warned that the party “may well slide back into extremism” after this moderation had failed to bear fruit at the polls. That prediction appears to have come true. Hindu nationalist sentiments have become mainstream in India thanks to the BJP. The BJP’s majoritarian vision has tremendous currency across India today, and its 2019 election victory is a byproduct of that.

Shrewdly, the party also co-opted some of the ideological ground of its sole competitor at the national level, the INC. The BJP learned a valuable lesson when it got pummeled in 2004 — it could not be perceived as negligent toward India’s poor and rural communities. When the BJP returned to power in 2014, it made governance and social services a priority, with initiatives to build toilets and accelerate financial inclusion. It also borrowed directly from the INC playbook by promising sops and subsidies to garner votes. The clearest example of this was the government’s announcement of a universal basic income for poor farmers in February 2019, mere months before the election.

For years the INC had castigated the BJP for being heartless toward India’s poor. In the 2019 election that narrative was harder to make stick. India’s two biggest parties ended up fighting the 2019 election by trying to outdo one another with their social welfare schemes, leaving the country without a major party advocating forcefully for markets and free trade. (If this trend continues, it could be a problem not just for India’s politics but for the country’s longer-term economic trajectory. Without significant reform and a stronger reliance on markets and trade, India simply cannot access the global supply chains it needs to grow at the pace necessary to create jobs and alleviate poverty.)

Socioeconomically, meanwhile, India has become a different country over the past 15 years. The economy has more than quadrupled in size since 2000 and vaulted from being the world’s 13th largest economy to the seventh. The middle class, which has been a consistent BJP voting bank, doubled from 300 million people to 600 million between 2004 and 2012 alone. This burgeoning middle class — those spending between $2 and $10 per capita per day — now makes up a large chunk of the Indian electorate. Devesh Kapur, a leading scholar on India, has written that the desires and demands of this new “aspirational” generation are remaking the Indian political landscape.

The rise of this aspirational middle class is a dramatic development with ramifications not just for India’s economy and its politics but for the rest of the world. This lifting up of living standards of hundreds of millions of people has turned India into one of the biggest consumer markets and the world’s third largest emitter of greenhouse gasses. Today, what happens in India, the largest democracy on earth and soon to be its most populous country, matters far beyond its borders.

More and more, this growing demographic in India embraces nationalism, seeks economic opportunity, demands clean and good governance, and desires greater respect for its homeland on the world stage. In 2014 and 2019, voters simply went for the party and leader they felt could best deliver.

Members of a Hindu nationalist group, RSS, march through Beawar in January 2020.

Pacific Press Agency/Alamy

magazine text block

A Leader for the Moment

One of the critical differences between defeat in 2004 and victory in 2019 involved the standard-bearers of the BJP; Vajpayee then, Modi now. Prime Minister Modi represents and speaks to the social currents that make India tick today. Kapur has written that “Modi’s India is aspirational, assertive — and anti-elite.” With his finger on the pulse of the Indian heartland, Modi is a natural leader for this moment in Indian history.

Unlike Vajpayee, Modi is beloved by the BJP’s Hindu right-wing and has helped usher in the Hindu nationalism now coursing through India’s streets. Because of his early links to the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the Hindu nationalist grassroots organization, the party’s ideological base views him as its own. Modi faced broad domestic and international condemnation for his handling of the horrific religious riots in Gujarat in 2002, which many critics and scholars describe as an anti-Muslim pogrom. However, the incident only endeared him further to his RSS supporters, who saw him as a leader that would stridently defend Hindus in India’s wars, cultural and otherwise.

Modi has returned the favor by delivering on several long-standing and highly coveted RSS priorities, including the provocative revocation of the special autonomy of the state of Jammu and Kashmir, legal permission to build the controversial Ram temple in Ayodhya, passage of a divisive Citizenship Amendment Act that provides a path to citizenship to non-Muslim migrants that fled religious persecution from three Muslim-majority countries, and the criminalization of “triple talaq,” the regressive “instant divorce” practiced by some Muslims in India.

In addition, his modest roots and unlikely journey from tea seller to prime minister are a compelling counterpoint to the dynastic INC, which has been controlled by the

Nehru/Gandhi family for much of India’s independent history. Modi’s lack of esteem for Western manners and his insistence on delivering speeches in Hindi are also strong rejoinders to the perceived pretensions of the Delhi political elite and the detachment of the INC in particular.

Simply put, many Indians believe that Modi represents and speaks for them.

Modi’s successful economic tenure as chief minister of Gujarat cemented his credibility as an uncorrupt and efficient economic steward. Even though his boldest economic gambit — demonetization — failed spectacularly, it reinforced voters’ perceptions of him as a leader of action. The countless Indians who have grown impatient with the country’s speed of progress see Modi as a kindred soul, laboring to transform India’s economy despite challenges from a decrepit bureaucracy.

Modi has also been at the forefront of co-opting the INC’s social welfare platform by focusing and delivering on social services. Government spending on social services such as health, education, housing, and water dropped under the BJP government of Vajpayee. While Modi was not necessarily better in all of these areas during his first term, his initiatives on sanitation, financial inclusion, and electrification have brought real change on the ground, and Indians have taken notice.

A BJP rally in Kolkata ahead of the May 2019 election.

Sopa Images Limited/Alamy

magazine text block

In his study of Indian voters, Milan Vaishnav of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace has found that in India “most successful politicians have mastered the art of skillfully combining both types of appeals” — economic and identity. In addition to endorsing a Hindu-right social agenda, Modi has skillfully exploited national identity in his approach to national security. The prime minister has whipped supporters and the Indian press into a nationalistic frenzy against neighboring Pakistan, responding to terrorist attacks emanating from Pakistan with bluster and confrontation.

After showing an openness to dialogue with Pakistan early in his first term, Modi quickly pivoted to a tough approach. He initially paused peace talks with Pakistan after the Pathankot attack in January 2016 and later ordered “surgical strikes” in Pakistan-administered Kashmir in response to an attack on the town of Uri. By publicly announcing such a retaliatory attack for the first time and suspending all talks with Pakistan, Modi heightened bilateral tensions further.

With diplomacy frozen, the Pulwama terrorist attack in February 2019 created a nationalist uproar in India that ultimately sealed the BJP win. Again, Modi went one step further in his response than India had in the past, ordering an attack on Pakistani territory beyond Pakistan-administered Kashmir.

Even though scant evidence has emerged that India’s military response accomplished the objectives the government claimed, Modi won the battle of narratives domestically by upping the ante and positioning himself as the protector of the country. The ensuing India-Pakistan crisis dominated the news cycle for an entire month, upending the campaign and undermining the opposition’s economic message just before elections. Modi’s political handling of the Pulwama attack was the turning point of the 2019 election. If the 2004 election was fought over the economy, the 2019 election was ultimately about national security.

Modi has officially diverged from the path of restraint that Indian leaders traversed in the 2000s. Both Vajpayee and his successor Manmohan Singh made the politically difficult decision to forgo confrontation for the sake of stability. Modi has benefited politically by rejecting that logic, but in doing so he has made escalation more likely in future crises. For years the international community looked to India to be the responsible player in the nuclear rivalry with Pakistan. With that no longer a guarantee, the coming decades are likely to see a number of dangerous clashes on the subcontinent.

The BJP’s surprise loss in 2004 and its resounding victory in 2019 are apt bookends for Indian history in the first two decades of this century. Whether consciously or not, lessons learned from 2004 altered the BJP’s approach for politicking and governing, and eventually awarded it the reins of the Indian state for a second straight term. Making it all come together is Narendra Modi, the strongest leader India has had since Indira Gandhi, and one who is leaving a lasting mark.