magazine text block

Since 2020, as the COVID-19 pandemic raised the profile of public health experts, few have been as visible as Dr. Leana Wen. Through her appearances on CNN, columns in The Washington Post, and her popular Twitter feed, Wen has frequently offered guidance to ordinary Americans struggling to reorient their lives around the virus. During the pandemic’s first year, she was a staunch advocate for stricter mitigation measures; more recently, however, she has argued that the presence of vaccines and treatments allow the United States to transition to accommodating the virus — a position that has drawn criticism for being “harmful and ableist.”

Wen insists that she hasn’t flip-flopped. Indeed, she argues, her perspective on COVID is consistent with an approach to public health she has maintained throughout her career — that successful outcomes depend on earning the public’s trust and meeting people where they are. Born in Shanghai in 1983, Wen immigrated to the United States at the age of seven after her parents received political asylum. A precocious child, Wen began taking college courses at age 13 and graduated summa cum laude from Cal State Los Angeles five years later. After medical school, Wen was working as an emergency room physician when she developed a passion for public health, launching a career that included a notable stint as the health commissioner for the city of Baltimore.

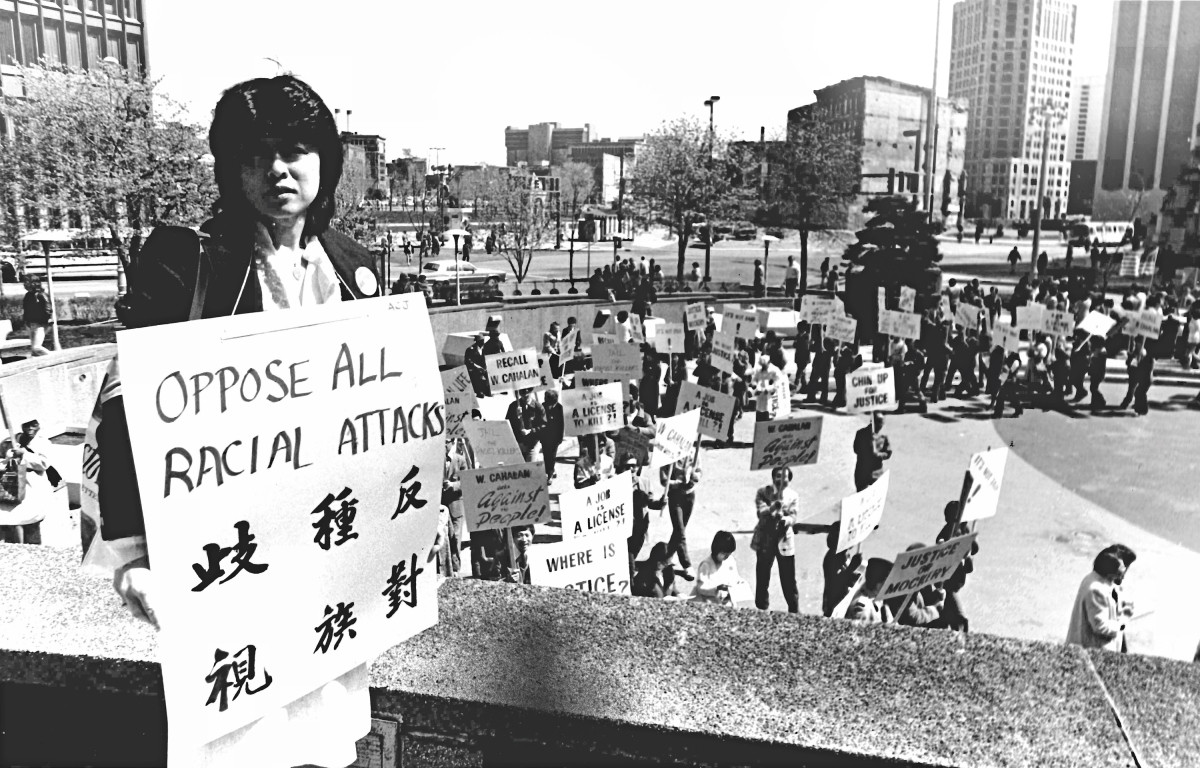

In this conversation with Asia Society Magazine, Wen discusses her earliest years in the U.S. and how they were formative in her decision to pursue a career in public health. She also details the lessons she learned from dealing with the opioid crisis and why, despite receiving a torrent of racially-charged abuse on social media, she feels it’s nevertheless important to participate in the discourse.

magazine text block

Matt Schiavenza: You were born in Shanghai and spent your first years there. What are your memories from this period?

Leana Wen: I grew up in a small, one-room apartment with my grandparents. My father was there also; my mother came and went because she was a student at the time and wasn’t able to live with us. We just had this one small room, and shared communal restrooms with others who lived on our floor. People would cook in the hallway, which would trigger my severe asthma. We were a close-knit, large family — there were always cousins and aunts and uncles around. My grandmother used to love making dumplings, and everyone would come in and out of the apartment.

To go from that life to where my parents and I ended up in the U.S. was profoundly different. We went from a city of 20 million people to living in a small town in the mountains of Utah. I was taken away from my large, extended family. It was a dramatic change of experience.

What was Utah like for you and your family?

Utah was my first introduction to the United States. We lived there for nearly three years, and it was quite an important time in my life. We had moved to a place without English as a Second Language (ESL) instruction — because it wasn’t like there were other people who didn’t speak English, right?

My family and I experienced the kindness of strangers. I remember when we first arrived in December 1990, it was the middle of winter. I had never seen snow. I remember wearing five sweaters because we didn’t have winter coats. Immediately, when I’d go outside, my shoes would get drenched because we couldn’t afford boots. One day, after we arrived, we found a whole bag of donated items: food, blankets, and winter coats.

My classmates didn’t make fun of me for not speaking English. Instead, they taught me. We were introduced to a local church where adults and children taught my family English in their spare time. That’s the kindness we experienced — and that’s what I associated with America. These people had no reason to be kind to us, but they did so because that was in their hearts: to treat everyone with compassion and kindness.

We went from that environment, which was a nurturing, small community where people helped each other out, to Los Angeles, where the initial years were very difficult. Despite being working professionals in China, my parents really struggled to find stable jobs and make ends meet. My father was an engineer in China, and in L.A. he delivered newspapers and washed dishes in a restaurant. My mother, who was studying to be a schoolteacher, worked in a video store and cleaned hotel rooms. We moved often and experienced bouts of homelessness because we couldn’t afford to pay rent. I went to a lot of schools in quick succession, including in areas where there was a lot of poverty and crime. It was extremely challenging.

magazine quote block

magazine text block

Was living in L.A. formative in terms of your Asian American identity?

Race, or my Asian American identity, was not something I ever truly thought of. I understood that I looked different from others and may have spoken a different language at home. But I felt at that point like I was just an American. That’s what I wanted to be.

I grew up in communities in Los Angeles that were predominantly not Asian American. People were mainly Latino or African American. I think only one school I attended had a large Asian American population. I never belonged to a Chinese American or Asian American association. It’s not because I deny my identity. It’s just not something I would have belonged to. It wasn’t until many years later that I identified with the concept of Asian Americanness.

How did your family’s struggles during your childhood influence your decision to pursue public health?

So much of my upbringing is a story of the success of and the necessity of public health. In my recent memoir Lifelines, I recounted that when I was about 10, I had a neighbor, a boy a couple of years younger than me, who had an asthma attack. Even though I was young, I knew from having asthma myself that if you have an attack, you need help beyond what you can do at home. But the boy’s grandmother was too afraid to call for help because the family was undocumented. She was afraid of having immigration authorities come to their home. As a result of this enormous fear, the boy died. When I watched this happen, I had the sense that we live in a society that was profoundly unequal.

From that early age, I felt strongly about going into medicine, specifically to work in the emergency room, where I would not have to turn patients away because of an inability to pay, or because of where they came from, or their immigration status. I believe very strongly that a basic level of decent health care should be a human right.

I didn’t study public health in college or even medical school. But when I worked in the ER, I began to see how failures in medical care could be traced back to public health. I saw patients who became ill — not because there wasn’t medication for them, but because they couldn’t afford it. Or when I’d tell my patients that they’d need to eat healthier foods in order to control their congestive heart failure, they’d tell me how difficult that was: They’d have to take three buses to get to Whole Foods, and then they couldn’t afford the fruit there, anyway. I was able to trace the importance of public health back to my childhood, where my family and I benefited from Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program. When my mother was pregnant with my sister, she had access to the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) insurance program. This enabled my sister and I to fulfill our wildest dreams.

magazine text block

During the 2010s, you served as the health commissioner in Baltimore, a time when opioid abuse was a major public health crisis. From the benefit of hindsight: What could we, as a society, have done differently? What have we learned from it?

One thing is to recognize that prevention is the best medicine. Many people became addicted to opioids because they didn’t understand that they were harmful. A lot of this had to do with misleading and deliberately false marketing by Purdue Pharmaceuticals and some of the other companies. I think there were many instances in my own medical practice where we reached for opioids first, as opposed to considering them in the context of benefits and risks, including downstream risks. And I think that’s something that the medical profession has to reckon with.

The second thing we learned is that we tend to treat addiction differently depending on who is suffering from it. In Baltimore, I often heard people say, “Why is it that we’re suddenly treating addiction as a disease? Is it because it’s now white people in suburban areas who are being affected?” Do we now care because it’s college-age white people who are dying, rather than when it was something that seemed to affect Black and brown communities? Then, we attributed addiction as a moral failing — if you became addicted and died, it was your fault. I think we have to recognize that there are structural inequalities, and that structural racism led us to where we are.

The third component, related to addiction being a disease, is to recognize that treatment exists, recovery is possible, and that we need to treat addiction and all mental health issues in the same way that we would treat physical health. If a person is diagnosed with depression, they should be given time off and the same level of care that they would have gotten had they been diagnosed with HIV. In 2015, I issued a standing order for naloxone, or Narcan, the opioid antidote, so that everyone in the city could essentially get it over the counter. We also did over 30,000 trainings for how to use it, and in three years, everyday residents saved the lives of more than 3,000 family members, friends, and other Baltimoreans. That’s the kind of work we have to do to reduce stigma and to send the message that addiction is a treatable disease.

How did you apply the lessons you learned in Baltimore to the COVID-19 pandemic?

The first thing is that public health depends on public trust. You’re not going to get very far in improving people’s health if you don’t get their buy in. This is especially true during a pandemic, where we’re asking people to do things that they previously did not do. We don’t come from a mask-wearing culture. It’s very difficult to convince people to isolate and quarantine themselves when that means not seeing their family and potentially losing wages. To get people to understand why, you have to explain and overexplain and have credible messengers and trusted people to convey the message.

You have to meet people where they are. If people are moving on from the pandemic, and you’re still telling them that they need to have restrictions on their lives, they’re going to stop trusting you — not only on this issue, but on other issues, too. That’s what’s been particularly important in helping people to navigate the times that we’re in, explaining the how and they why, over and over again, and helping people weigh the risk calculus for their own lives.

Health disparities didn’t start with COVID — COVID just unmasked them. Social determinants are a core principle in public health: Health isn’t just affected by the health care you receive, it’s also integrally tied to housing, access to education, poverty, food, all these other things, too.

Working in public health has shown me also how much of it is forgotten. There’s a saying that public health saved your life today — you just don’t know it. By definition, it works when it’s invisible, when we’ve prevented something from happening. The problem is, because it’s invisible, it becomes the first thing that’s on the chopping block when it comes to budget time. And that’s a major problem. We’ve seen during the pandemic that there’s a cycle of panic and neglect, that people care when there’s a crisis that affects them but once it’s over, they don’t care about public health anymore. I think the biggest challenge we have going forward is to help people move on and live with COVID, while at the same time not forgetting that we need to prepare for the next variant and the next pandemic.

magazine quote block

magazine text block

You’ve been a public figure for a while, and you’re not shy about expressing your opinion on TV and in platforms like Twitter. You’ve experienced a lot of blowback and criticism. How does being a woman of color, in particular an Asian American woman, change the way people interact with you? Does it ever make you reconsider the value of engaging?

There have been a number of studies that have shown that women, particularly women of color, receive a disproportionate amount of harassment over social media and other platforms. All someone has to do is search my name, and you can see photoshopped images of my head onto Mao Zedong’s body, or people who have called me Minnie Mouse. On Twitter, specifically, there are racist and misogynistic accounts from all over the political spectrum. I have received death threats aimed at my family, including my young children, that no one should find to be acceptable.

By the way, this isn’t unique to me. We’ve seen public health experts engaging in the public discourse being targeted all throughout the country and world. And it’s dissuading many people from engagement. That’s my fear. We don’t want to be living in a world where the loudest, most extreme voices are the only ones out there. We also don’t want to live in a world where the bullies succeed in pushing out individuals who represent groups that have traditionally been marginalized.

That’s the reason I continue to engage. I do place limits on these engagements, such as blocking people on Twitter who I believe are inflaming the discourse; people who, on purpose, take my comments out of context in order to drive up the anger of their supporters. I think we, as an academic community, as reasonable members of society, need to aim for discourse that's civil, nuanced, and respectful of one another.