magazine text block

At the very start of 2020, Hong Kong felt alive — and angry. On January 1, more than a million protesters marched through the city as part of a pro-democracy rally. At first, these gatherings were orderly and harmonious, but clashes with the police changed the mood entirely.

It wasn’t long before the spread of the coronavirus made such gatherings impossible. Fear of the pandemic briefly caused consumers to panic-shop and hoard supplies like toilet paper and bleach. Face masks, for a population that had already lived through SARS, quickly became ubiquitous.

But as February turned to March, Hong Kong became quiet — quieter than I’ve ever experienced it before. The government imposed restrictions on gatherings, ostensibly to control the spread of the virus. But these limits also functioned as a convenient excuse to dampen the protest movement.

Once, the police told me to leave a site I was photographing because I might initiate a gathering — even though I was alone at the time. Meanwhile, scenes of crowded bars in Lan Kwai Fong, Wan Chai, and Sai Kung, filled with maskless patrons, indicated that social distancing rules weren’t always applied equally.

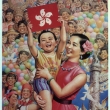

A protester flashes a five-finger gesture representing the movement's “five demands” during a march organized by the Civil Human Rights Front on January 1, 2020, in Causeway Bay, Hong Kong.

May James

magazine text block

Practicing journalism in Hong Kong has become much more difficult. The territory’s police commissioner said that only “trusted media” should be allowed inside cordoned-off crime scenes, excluding journalists from Reuters, the Associated Press, and Agence France Presse. After an incident last year in which the police arrested me for asking for their warrant card — a right Hong Kong residents have — I’m not sure whether I’m considered trusted media or not.

One day, as I photographed protest detainees, the police approached me and searched my bag. They asked me to state my name while they filmed me. Carrie Lam, Hong Kong’s chief executive, says that the media has a role in monitoring the government and that free speech is a core value. But the trend is inauspicious. A Hong Kong reporter who covered the storming of the Legislative Council last summer is now facing charges for rioting. The new national security law — which Lam says will target only a tiny minority of people who have broken the law — has granted Hong Kong police vastly expanded powers to conduct warrantless raids and surveillance. The law has already been used to arrest protesters, disqualify pro-democracy legislative candidates, and charge opposition figures. And the arrest of Jimmy Lai, following a raid on his Apple Daily offices, indicates that journalists will not be spared.

Hong Kong is changing. People now worry about what they say. This year, for the first time, I’ve felt nervous about exhibiting my photography. The city itself even looks different. Barricades and metal fences, installed to repel protesters, are now everywhere, and even the once-welcoming international airport is guarded by metal wire. Family members who once saw their loved ones off inside the building are now relegated to outside.

Hong Kong has long been a haven for immigrants seeking a better life. But I can’t help but wonder if it’s now us — native Hong Kongers — who should be considered refugees.

Police officers stand guard in the Mongkok area of Hong Kong on May 27, 2020, during a protest that saw 300 people arrested for unauthorized assembly.

May James

Butchers wait for customers at a wet market in Wan Chai District during the COVID-19 pandemic in Hong Kong on February 26, 2020.

May James

A photo taken at the University of Hong Kong on June 4, 2020, the 31st anniversary of the Tiananmen Square Massacre, shows a newly repainted slogan in Chinese. It reads: “冷血屠城烈士英魂不朽; 誓殲豺狼民主星火不滅” or “The heroic souls of martyrs shall never perish despite the cold-blooded massacre; An oath to eliminate the jackals cannot extinguish the spark of democracy.”

May James

A pro-democracy supporter holds a copy of the Apple Daily newspaper with the headline "No fear in suppression," in front of Jimmy Lai’s vehicle as he leaves Mongkok police station on August 12, 2020. Lai, an outspoken pro-democracy advocate and Hong Kong media mogul who founded Apple Daily, had been arrested the day before under Hong Kong’s new National Security Law.

May James

Plain clothes police officers hold pepper spray while arresting a protester in the New Town Plaza shopping mall in Hong Kong’s Sha Tin District on May 13, 2020.

May James

Hong Kong Chief Executive Carrie Lam addresses the media during a press conference at Hong Kong’s Central Government Office on May 22, 2020, the day after the National Security Law was proposed.

May James

Pro-Beijing Hong Kongers celebrate the enactment of the National Security Law by drinking champagne, waving China and Hong Kong flags, and singing China’s national anthem in Hong Kong’s Tamar Park on June 30, 2020.

May James

A police officer looks at her phone at a popular bar area in Hong Kong’s Central District on May 29, 2020. Rules limiting public gatherings to eight people, imposed to control the spread of COVID-19, were routinely ignored in Hong Kong.

May James