magazine text block

Bernice Bing

by Vivienne Liu

Research Assistant for Contemporary Art, Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

Bernice Bing was a painter associated with the Bay Area Figurative Movement and Beat Generation. Despite studying under the likes of Richard Diebenkorn and Frank Lobdell and exhibiting alongside contemporaries such as Manuel Neri and Jay DeFeo, Bing remains overlooked and understudied — undoubtedly because she was queer, Chinese American, and a woman.

Bing rejected readings of social difference into her work, seeing them as simplistic and reductive. However, I contend that her intersecting identities created a complexity of being — a sense of multiplicity that allowed Bing to hold so many parts of the world together in generous tandem.

In her ever-evolving explorations of the unconscious mind, New Age spirituality, Eastern calligraphy, and natural Californian landscapes, as well as her roles as an artist, community organizer, and arts administrator, Bing demonstrates the ways that queer women of color contain infinite possibility.

Still from The Ark

Matt Huynh, 2017

From the collection of the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center

Matt Huynh

magazine text block

Matt Huynh

by Lawrence-Minh Bùi Davis

Curator of Asian Pacific American Studies, Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center

I first learned of artist Matt Huynh in 2015, when The Boat debuted — six years and counting later, arguably still the most cutting edge, ambitious “interactive graphic novel” any of us has seen.

Since that time, this Vietnamese Australian (now based in New York City) artist-illustrator-animator extraordinaire has authored a wide array of work, including, I’m happy to say, a number of projects in collaboration with the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center:

Kung Fu Zombies vs Shaman Warrior, a 2016 animated adaptation of a play-in-progress by Saymoukda Duangphouxay Vongsay; The Ark, a 2017 animated adaptation of the preface to Viet Thanh Nguyen’s then novel-in-progress The Committed; and On True War Stories, a graphic narrative adaptation of an essay by the same name by Nguyen, published in the Massachusetts Review in 2018, and collected in The Best American Nonrequired Reading 2019.

In mid-March 2021, when The New Yorker launched the groundbreaking Reeducated, a virtual reality documentary about the detention and political reeducation of ethnic and religious minorities in China, I wasn’t surprised to see Matt as its central artist.

Across his body of work, attuned especially to the lives and humanity of refugees, asylum seekers, and other migrant communities, Huynh is rethinking storytelling as embodied encounter, vertiginous and multisensory, unfamiliar and wondrous.

Kama

Monica Ramos, 2016

From the collection of the SmithsonianAsian Pacific American Center

Les Talusan

magazine text block

Monica Ramos

by Adriel Luis

Curator of Digital and Emerging Media, Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center

I love Monica Ramos’ work because of how it makes me rethink the human form.

Ramos’ illustrations sometimes include mythical creatures and celestial beings, but they ultimately speak to deeply personal issues such as migration, sexuality, and mental health.

In 2016, the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center collaborated with Monica to create Kama, a “jungle” of iconographies that represent identity as an interconnected universe that includes Filipino indigeneity, colonization, and diaspora. It exemplifies all of the traits that I love about Monica as an artist: beauty, whimsy, and depth.

"New York, New York 1979 (Statue of Liberty)"

from the East Meets West Self-Portrait Series 1979–1989

Tseng Kwong Chi, 1979

From the collection of Asia Society Museum

Tseng Kwong Chi

magazine text block

Tseng Kwong Chi

by Michelle Yun Mapplethorpe

Vice President for Global Artistic Programs, Asia Society; Director, Asia Society Museum

“New York, New York 1979 (Statue of Liberty)” from the East Meets West Self-Portrait Series 1979–1989, by Tseng Kwong Chi is one of my earliest associations with Asia Society Museum.

This artwork graces the catalogue cover of the museum’s first contemporary art exhibition: Asia/America: Identities in Contemporary Asian Art.

Encountering the photograph upon my arrival to New York as a young art historian, one of the few Asian Americans in the field at that time, it ignited a new awareness of powerful voices outside the Eurocentric perspective I had been schooled in.

The artist writes: “My photographs are social studies and social comments on Western society and its relationship with the East. [I pose] as a Chinese tourist in front of monuments of Europe, America, and elsewhere. ... I am an inquisitive traveler, a witness of my time, and an ambiguous ambassador.”

Twenty years later, serendipitously, I had the pleasure of acquiring the photograph for Asia Society as a tribute to the museum’s trailblazing roots in the field and a reminder of the power of images to impassion and inspire. Tseng’s photograph remains a touchstone for me. It exudes strength and solidarity with the ideas of liberty and freedom, yet also serves as a poignant reminder of the Asian American community’s ongoing status as the "other” in American society. And amidst the alarming rise of violence and discrimination against Asian Americans, it is a comforting symbol of the enduring strength of the contributions of Asian American artists.

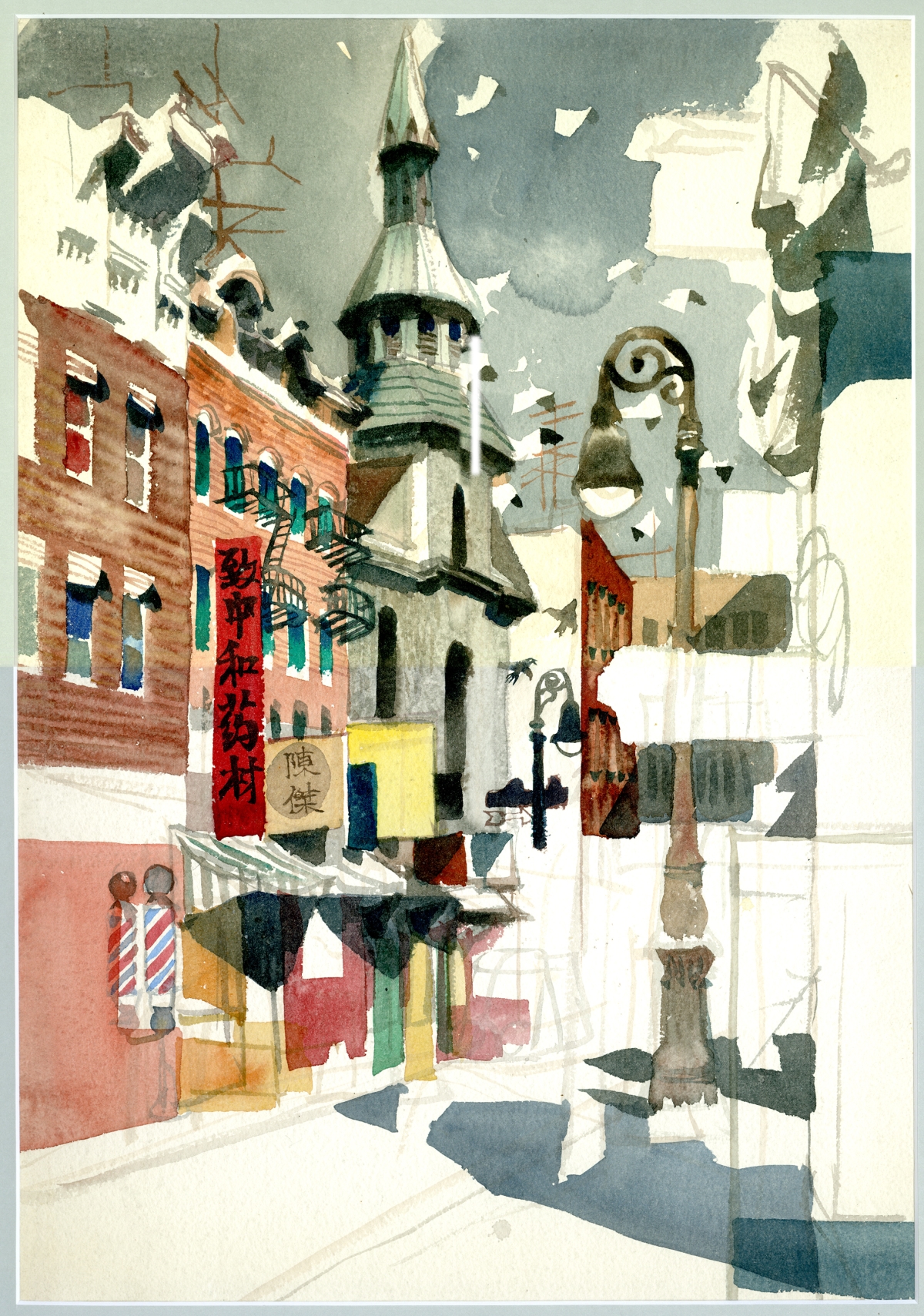

"Mott Street 2"

Dong Kingman, 1953

From the collection of the Museum of Chinese in America

Dong Kingman

magazine text block

Dong Kingman

by Herb Tam

Curator and Director of Exhibitions, Museum of Chinese in America (MOCA)

Dong Kingman was a pioneering Asian American artist back when the term "Asian American" had not been coined yet.

In fact, in the pre- and post-war periods in which Kingman was active, there were just a scant few visual artists of Asian descent who were pursuing a life in the arts.

However, Kingman’s ethnicity — he was born in 1911 to Chinese immigrants in Oakland, California — is not the only reason we should take a closer look at his work.

His “Mott Street 2” watercolor from 1953, likely painted on the spot in plein air, shows an assured colorist with an imaginative eye for dramatic light and shadow that recalls the seaside watercolors of Edward Hopper, Kingman’s contemporary.

It is an early painted depiction of New York City’s Chinatown and though it has been left unfinished, Kingman’s painting offers up important details. The tall spire of the historic Transfiguration Church in the background situates it immediately as Manhattan Chinatown’s Mott Street.

In the foreground, he carefully renders a red store sign for an herbal medicine shop on the ground floor of a quintessential New York tenement building, complete with rickety fire escapes and wiry TV antennas jutting from the roof.

The painting begs many questions: What was the artist thinking when he chose this view? Why did he stop in the middle? Who else was on the street that day?

I can easily imagine him walking towards Transfiguration, making a right on Pell Street, then another right down a windy Doyers Street to stop for a bite at Nom Wah Tea Parlor, the oldest dim sum restaurant in Chinatown.

A version of this story was originally published by Google Arts & Culture.