How Can Afghanistan's Cultural Heritage be Preserved?

Paul Bucherer is the Director of the Afghanistan Institute and Museum (Bibliotheca Afghanica) in Switzerland. The Bibliotheca Afghanica museum-in-exile serves as a temporary home for artifacts that have been loaned to Mr Bucherer by Afghans and others outside the country for safekeeping. The entire collection will be repatriated to Afghanistan as soon as it is safe to do so.

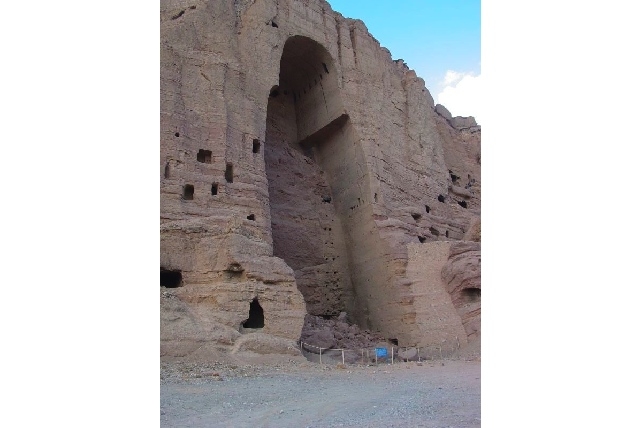

In this interview with The Asia Society, Mr Bucherer discusses the collection at the Bibliotheca Afghanica, the events leading up to the destruction of the Buddha statues in Bamiyan and the recent decision to rebuild them. Mr Bucherer was in Afghanistan earlier this year on a UNESCO mission, where he found universal support for their reconstruction. In this interview he also argues that, contrary to popular belief, it was under the increasing influence of Al-Qaeda that the decision to destroy the Buddhas was taken and that, in fact, local Taliban in Bamiyan refused to have any part in it.

Mr Bucherer was in New York in April for a panel discussion organized by the Asia Society entitled, "Beyond Bamiyan: Will the World be Ready Next Time?" The panel was organized to address current debates on the issue of cultural patrimony and the steps taken by the international community to protect cultural heritage. This program was made possible with the generous support of the Hazen Polsky Foundation.

Other panelists included Mounir Bouchenaki, Assistant Director General for Culture at UNESCO; Bonnie Burnham, President of the World Monuments Fund; Barbara Crossette, a reporter for The New York Times; James Cuno, Director of the Harvard University Art Museums; Philippe de Montebello, Director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; Derek Gillman, President of the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and Satoshi Yamato of the Agency for Cultural Affairs in Japan.

What prompted you to start the Afghanistan Museum in Bubendorf, Switzerland? What is the nature of the collection there? How did you come to have this collection and is it still growing?

The museum was started at the request of all the parties of the Afghan civil war: the Northern Alliance as well as the Taliban. Professor Burhanuddin Rabbani [former Afghan president and Northern Alliance leader] himself came to Switzerland to discuss this as did Abdullah Jamal, the Taliban minister of culture and information, who discussed this matter in his official capacity. It was really at the request of the Afghan people that this began.

We first suggested that Afghan artifacts should be housed in the existing Rietberg Museum in Zurich since they specialize in Asian arts, but the Afghans did not want their pieces mixed up with Indian, Japanese and Chinese material. Regardless of how modest a space it may be, the Afghans said they wanted their own museum to display exclusively Afghan artifacts.

The original idea of the Afghans was to bring to Switzerland all the holdings of the Kabul Museum and so to create primarily an archaeological museum. I should say that, perhaps, in this context, the word "museum" is wrong; we should speak instead about a temporary depot. It was only called "museum" because we also wanted to have a display to inform visitors about Afghan culture, which was not very well known or understood in the West after 20 years of war there.

When plans for this museum were just getting underway, you stressed that you did not intend to buy any materials from the market, but that you would rely on objects given to you from inside Afghanistan and elsewhere. Could you explain why this was the case? Have you stuck to this decision and if so, what about all the artifacts being sold illegally in Pakistan's black market? How would you get access to those?

There were two reasons for this: first, there was no necessity to buy. Second, the idea was that the Afghan State would donate these materials to a temporary depot. In the beginning there was no need at all to buy anything on the market since I knew that such a project was already underway under the auspices of SPACH [Society for the Preservation of Afghanistan's Cultural Heritage] in Islamabad and Peshawar. So there was no need to duplicate this effort.

We have maintained to this point that there is no need to buy anything on the market for two reasons: first, there is an agreement with UNESCO which forbids us absolutely from doing so. The second reason is much more practical: we do not have the money.

As far as the artifacts in Pakistan are concerned, I would say that 90 to 95 per cent of them are sold on the black market. As far as I know, according to Afghan and Pakistani dealers, most of these artifacts go to Japan. SPACH only buys limited, single items, which were looted from the Kabul Museum. Even Japanese collectors hesitate to buy objects which are known to be looted from the official museum collections.

One dealer, for instance, owned a marvelous piece, one of the most important Gandharan pieces that I have ever seen, with figures of Indic and Greek peoples on the same stone, and Buddha in the middle. The dealer to whom this object belongs was asking $40,000 for it. He could not sell it for many years and had himself paid $30,000 or something like that for it. He offered it to me at the same cost but I refused because I could not buy it [for the reasons above]. So he broke the object, which was by itself quite large, into smaller individual figures and was planning to sell each separately. He hopes that he will then be able to get his money back.

Is it true that in 1998, Pakistan passed a law appropriating all Gandharan antiquities found within the country's borders? If so, what are the implications of this for Afghanistan's cultural heritage?

I have never seen the original text of this law. What I understand from my Afghan and Pakistani friends is that the law states that all antique material which remains for at least one year on Pakistani soil automatically becomes Pakistani cultural heritage and may not be exported. Since most of the Afghan material is brought to Pakistan it becomes Pakistani cultural heritage, and may not be exported back to Afghanistan since there are no import papers for this material.

You have been leading the initiative to have the Buddhas rebuilt using highly detailed photogrammetric measurements of the larger statue. How do you respond to criticism that this $40 - $50 million project will take away from much needed humanitarian aid in the country?

I have spoken about this question with many ordinary people in the bazaars and markets in Afghanistan. To make them understand how expensive an undertaking this is, I told them repeatedly that to reconstruct only one of the statues would cost the same price as the reconstruction of 30 bridges. I could not find one single Afghan among the many different groups I spoke with who said that 30 or 40 bridges would be more important; they all said the Buddhas are something they need, and the bridges will come eventually anyway.

Many people say now that the destruction of Bamiyan is something which only harmed the Shia Hazara community in Central Afghanistan. This is simply not correct. I was in the Pashtun area of Mehtar Lam and I spoke to the Pashtuns about the destruction of the Buddhas in Bamiyan and tears came to their eyes and they started to cry about the loss of this national cultural heritage.

People also ask how one can speak of the extremely costly reconstruction of cultural heritage in the face of the poverty that is so widespread in Afghanistan. As far as this issue is concerned, there are possibilities of getting funding from sources which would never be ready to provide any humanitarian aid; in other words, this project would not detract at all from the humanitarian funds sought for Afghanistan. We should make use of the funds we receive for this project because they will not otherwise be allocated for other work in the country; they will simply be lost for Afghanistan.

You said after your recent trip to Afghanistan that in fact the Taliban (as well as other Afghans) were completely opposed to the destruction of the Bamiyan Buddhas and it was only under the influence of Al-Qaeda that this occurred. Could you please explain this?

In December 2000, three months before the destruction of the Buddhas, I was in Kandahar and I spoke to the leaders of the Taliban, although not to Mullah Omar (he did not agree to see me since I am not a Muslim). I did however meet with the second-in-command, who demonstrated to me in different ways how the Taliban were no longer masters in their own house.

The person I met with was the second man in the official Taliban hierarchy and he came himself with me in his car to a specific place and told me that I could take photographs; he gave me explicit permission to do so. Then Al-Qaeda people with Kalashnikovs came towards us and waved us away. And the person I was with, someone so senior in the Taliban hierarchy, could do nothing to stop them. These people were quite obviously Al-Qaeda; they were clearly not Afghans since they spoke neither Pashto nor Dari. There was no discussion possible with them as I do not speak Arabic.

The same thing happened later on in Kabul, around early January 2001, when I had meetings regarding Bamiyan with the Minister of Information and Culture, Qudratullah Jamal, who told me that his hands were tied. He said in fact that had I done something two or three weeks earlier, when I was first asked by the Taliban and other Afghans for assistance, he could have done everything to assist me but now he insisted that he was no longer in a position to do anything at all.

When I was in Kabul in January 2002, I went to the storerooms of the Kabul Museum with the caretakers of the rooms who are personally responsible for every single item there, and they too told me that the destruction was done by a group of ten men, two of them Afghans, and the rest foreigners.

Why do you think no one reported this at the time? Why was this nowhere in the papers then?

A lot of people were aware of it. The Afghans even wrote letters to the outside world to ask for help. Already in October 1998 the head of the little Buddha in Bamiyan was blown up and the entire world community was aware that this happened. I was there in July 1998 and then again in October 1998 and I had taken photographs of the Buddha, one with the head intact, and the later one with part of the head missing. I sent these photographs everywhere; they were published in the International Art Newspaper but nobody did anything.

Shortly afterwards, Mullah Omar issued a decree for the protection of these statues and the international community was satisfied that they would be safe. At the same time, though, the Afghans themselves knew that it was not the end of the destruction. This was the reason they asked to start this museum in exile.

The international community may not have focused sufficiently on the threat to the statues, but surely their subsequent destruction should have made it clear that the influence of Al-Qaeda had grown exponentially within the Taliban and in Afghanistan generally (especially given Mullah Omar's decree earlier).

The growing influence of Al-Qaeda, I think, is the result of two different factors. The first factor has to do with the UN sanctions; since nobody else was able to have contact with the Taliban, they were pushed into the arms of Al-Qaeda. The Taliban essentially had access only to Osama bin Laden and his Al-Qaeda network since the international community had completely blocked any contact with the Taliban.

The second point is that Afghanistan had reached an extraordinary position in the eyes of the whole Islamic world because they managed to get rid of the British in the 19th century, and then of the Soviets in the 20th century. The Al-Qaeda, which is a Wahhabi movement, has been proselytizing in Afghanistan since the beginning of the 20th century. In fact, the very first printed publication in Afghanistan is a pamphlet against Wahhabi proselytizing in Konar Valley in 1907.

Afghanistan under the Taliban presented a unique possibility for Wahhabis; if they had managed to make Afghanistan predominantly Wahhabi, Wahhabism would have had an enormous boost in the whole Islamic world. Afghan society was very weak after 20 years of war, they could not put up any real resistance.

This was an action from within. It was not an enemy from outside like the Russians had been; these Wahhabis were already within, they were comrades-in-arms, they fought alongside the Afghans against the Soviets. Abdul Haq [one of the military leaders of the Afghan resistance who was murdered in the beginning of the fight against Al-Qaeda in 2001] told me it was so easy to fight the Soviets because the Afghans could at least identify who to fight, but now (this was in 1997 or 1998) it is very difficult to know who Afghanistan's enemies are.

When does UNESCO convene the meeting on whether the Buddhas in Bamiyan should be rebuilt? What conclusions are likely to be reached at this meeting and how are Afghans involved in the process?

I was personally asked to prepare an investigation regarding the different possibilities for reconstruction, the problems involved, the costs, the priorities, what needs to be done now and what can be postponed till later. Ultimately, it will be up to international groups of experts to give their advice from the perspective of archaeologists, art historians, and so on. Then when all the cards are on the table, the Afghans will decide which card they will play.

What do you think are the limitations of present agreements governing the preservation of cultural heritage?

The most important thing is that the protection of cultural heritage should not be abused in a colonial kind of way. We should accept that this cultural heritage is the cultural heritage of the Afghan people. They are proud of it. We, too, from the West may like it, may give our support to protect it, but it does not belong to us. It is not up to us to decide what has to be done. The Afghans are able and ready to decide. They will ask our advice but in the end they will decide for themselves.

Interview conducted by Nermeen Shaikh of The Asia Society.