You Went Where For Spring Break?!

Students Develop Global Competence in Cuba

"I have long believed, as have many before me, that peaceful relations between nations requires understanding and mutual respect between individuals." - President Dwight D. Eisenhower, Founder of People to People International

For many high school students, taking a spring break vacation can be somewhat of a rite of passage. Spending time with family and friends is a respite from their studies and a chance to find a bit of carefree space in their lives. When I was a teacher, my students would often return to my classroom with stories of beaches, amusement parks, family reunions, or relaxing “staycations,” where they just spent time hanging out at home. For the teachers of 38 high school students around the United States, the stories they heard upon their return to school last month sounded very different. These students told tales of architecture dating back to the early 1900s, automobiles from the 1950s, negotiating the use of a different language and currency, while experiencing a culture rich in tradition and unmarked by Starbucks or McDonald’s. They shared stories of new friendships and a deeper understanding and appreciation for what it means to be a citizen of the United States and the world. In fact, their spring break was not quite a break.

People to People International (PTPI) organized an educational and cultural program for two delegations of American high school students to go to Cuba, a unique opportunity that few American adults have experienced. Founded in 1956 by President Dwight D. Eisenhower, PTPI promotes international understanding and friendship through educational, cultural, and humanitarian activities while emphasizing personal diplomacy and nongovernmental contacts among people. Eisenhower realized the importance of uniting ordinary citizens from different countries to foster understanding and respect. He believed that, in particular, by bringing youth together from different countries, they would be more likely to overcome ideological differences and, ultimately, not succumb to war.

The Cuba trip was made possible through a special people-to-people license granted by the U.S. Treasury Department, Office of Foreign Asset Control (OFAC). (Officially licensed travel is currently the only legal way for U.S. residents to visit Cuba.) The program was designed to provide students a rare glimpse into the country’s rich history, as well as a chance to meet with the Cuban people.

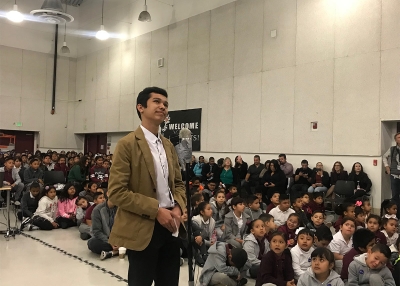

I was honored to lead such a special delegation. The experience was framed in a way that develops student global competency. Global competence is the capacity and disposition to understand and act on issues of global significance. More specifically, it involves them investigating the world, In a purposeful, inquiry-based design, each activity gave them opportunities to apply these skills in authentic settings, taking full advantage of the rich and dynamic Cuban culture that still remains a mystery to many Americans today.

The students were given four questions to consider: 1) what do you want to know? 2) how will you find answers? 3) how do you share information? and 4) now what? I will outline the process below, with real examples from the Cuban study trip, so you may apply the same experiential learning in different contexts. This exercise that helps build student global competence can work in local school communities just as it does on a study abroad trips.

What Do You Want to Know?

Prior to leaving for Cuba, students divided into research teams based on their own interests. The teams focused on arts and culture, the environment, social welfare, religion, and education. Daily life in Cuba and the experiences of the people there was somewhat of an unknown going into this program, yet provided an opportunity to pose engaging questions to understand the context of where they were going. Because the students live in different parts of the United States, they met via conference calls and used social media to begin their research. This served as a powerful example of how technology can bridge geographic and cultural divides. Students in innovative schools today are already networking, talking, and collaborating with their peers, many of whom they may not have ever met in person. The students faced challenges when collecting information about their topic; they questioned the accuracy of the information they found, whether it was on the Internet or through conversations with adults. Being critical consumers of their information is an essential part of investigating the world and weighing perspectives.

Inquiry-based projects reveal many layers of questions. Once on the ground in Cuba, the research teams collectively honed in on several research questions to guide their study. For example, the team focusing on social welfare had heard a great deal about the high quality and free access to health care provided to Cuban citizens. They framed their research to answer the question, “What makes the Cuban health care system so good?” The arts and culture group decided to focus on how Cuban artists used their art to express themselves and their beliefs about social realities. These were not research questions I assigned. My role involved pushing student thinking to deeper levels by helping them get beyond yes or no or other easily answerable questions. They rose to the challenge. Students owned the learning and guided the direction their research would take..

How will you find answers?

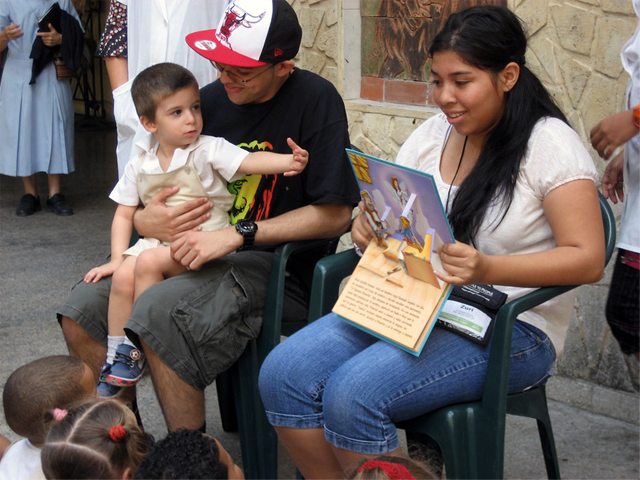

The teams were challenged to design a data collection plan for their research questions. Each team reviewed the itinerary, which included a visit to a church, organic farm, and a day care center, among other stops. The teams had to determine who would provide them with the best and most accurate information about their topic. We discussed how to conduct interviews, strategies for making observations and how to enter into conversations with local citizens in a way that was appropriate and welcoming. The students quickly realized that approaching people with a notebook in hand asking a bunch of questions could be intimidating! Instead, each team developed an interview protocol and decided what role each team member would take in the process. For example, not all of the students spoke Spanish, so those students who were more fluent quickly emerged and helped facilitate dialogue with the locals who did not speak English.

It’s worth mentioning here that we were welcomed quite warmly by the citizens of Cuba wherever we went. Their natural curiosity and interest in learning about the United States and what our impressions about their country were palpable. What was also evident throughout our interactions was the tremendous pride they all held for their culture and history. Politics aside, our students engaged them in conversations about their hopes, dreams, and desires for the future. In addition to the formal stops on our itinerary, it was not uncommon to see small groups of the students just hanging out in the lobby of our hotel talking to waiters, the concierge, and anyone else they thought could provide interesting perspectives on their topic. When given the license and purpose, students found that anyone and everyone served as a potential source of information and could provide new insights or an avenue to investigate. These ongoing conversations compelled students to examine Cuban perspectives and weigh those perspectives against their own.

How will you share this information?

It was important to provide time for the students to make sense of what they heard and learned each day. Each team developed group norms on how they would meet, talk, and help each other through their research project. Through whole-group team-building activities and discussions, we created a time for students to share and talk freely about their thoughts, questions, and concerns. In small groups, another dedicated time, they reviewed their notes, discussed new learning from the day, and posed new questions that needed to be answered in an effort to address their research questions. It was not unusual to see one team share information with another team if they had collected information pertinent to their topic.

In an attempt to help students synthesize everything they had learned, we engaged them in a debate towards the end of the program regarding the U.S. Embargo: “Should the embargo and travel restrictions be lifted? Why or why not?” This led to a lively debate between the two sides, each offering compelling examples and rationale based on what they had learned throughout the program. Their level of analysis of the situation, the benefits and drawbacks of such a policy and the human impact were amazing indications of their growth over the course of the week. This type of learning could never be measured on a standardized test.

Now what?

Throughout the week, we revisited the concept of global competence. The students had, in fact, investigated the world, recognized perspectives, and communicated ideas very successfully. However, we didn’t want this learning to end with them and in this location.

As the culminating aspect of the program, the teams were asked to develop a plan of advocacy or action. Because they had been afforded this unique experience to visit a country that so few Americans have really been able to experience, there was almost an obligation to share this information with their families, school community, and the broader American audience. Each team devised a plan for how they would share their learning and experience to a broader community. Websites, blog posts, letters to local and state representatives, and public presentations were just some of the student plans. The overarching goal in each seemed to be focused on educating the American public about life in Cuba, while dispelling some of the myths and confirming some of the challenges that still exist there.

Implications for the Field

Travel provides one of the most authentic, eye-opening opportunities for students to step out of their comfort zone, challenge their perspectives and develop new understanding of others. This is best demonstrated by the reflections of three students:

"I had thought that I had a good understanding of Cuba before I went because I did a research project on it in world issues class. Once I landed in Cuba I noticed that I hadn't taken into consideration the culture, and overall mood of the country that you can only get by being on the ground and breathing the same air." – Mary (Cincinnati, Ohio, USA)

"Traveling to Cuba completely changed my outlook toward life. Visiting a foreign country that is totally different from America allowed me to gain new insight on a completely different world. Everything I experienced in Cuba I relate back to life in America, which helps me realize how fortunate we all are". – Travis (Lubbock, Texas, USA)

"It was all so unique and very interesting experiencing a culture that is so close physically but so distant culturally. The trip also gave me insight into myself and helped me realize how my assumptions and stereotypes of things such as Cuba are often wrong. Overall it was a life-changing experience!" – Julien (Wever, Iowa, USA)

True to the mission set forth by President Eisenhower when he founded PTPI, these students represented their country with distinction, helping to foster stronger ties and good will internationally. In some cases, they have done it better than we have as adults.

In these tough economic times, travel of this nature may not be an option for all students or schools. It is critical that as educators, we find other ways to expose students to different cultures, and to get them outside of the classroom and interacting in meaningful ways with people different than themselves. Taking an inquiry stance in our classrooms is one of the only ways we can truly engage students, increase student motivation, and develop self-reliance.

Just as important as the travel component is the power of allowing students choice in their learning and allowing them to guide that learning. As the teacher, I set out broad parameters for the activities, but they drove where the conversations went, how they worked as teams, and controlled how they demonstrated their learning. In the end, there was no doubt in my mind that they left with a deeper understanding of the culture and history of Cuba, while developing interpersonal and personal skills along the way.

It is my hope in sharing this experience to provide a model for teachers and schools to follow with their students. It does not require you to take students to Cuba to engage them in an authentic, inquiry-based learning experience. The same process outlined above can be applied in your local setting, exploring issues and topics relevant to your community. It does require, however, that you provide them multiple opportunities to engage in and with the world in meaningful ways.