Disciplinary and Interdisciplinary Study

This article was adapted from Veronica Boix-Mansilla and Anthony Jackson's book, Educating for Global Competence: Preparing Our Youth to Engage the World. Read the full chapter, Understanding the World through Disciplinary and Interdisciplinary Study (15-page PDF).

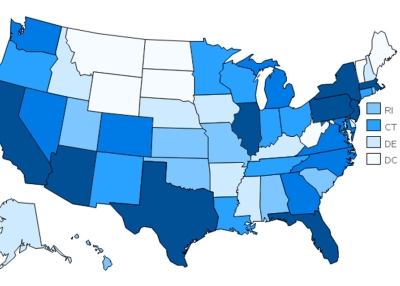

Global competence is the capacity to use knowledge and skills in a global knowledge economy. (See the full definition here.) But globally competent students learn to view the world through the lenses of history, science, mathematics, and through language, the arts, among other disciplines. They also integrate such lenses to reach deeper, more comprehensive, and personally meaningful insights.

Clearly, neither students nor experts can master the large amounts of available information about world geography, history, economics, anthropology, and art.

Gaining global competence is not merely a matter of having more information about more places in the world. Rather, students’ global competence pivots on their growing ability to understand contexts, telling phenomena, and revealing transnational connections in depth. Over time, such substantive and developmentally appropriate engagement with disciplines and topics of global significance will build the foundation for global competence.

Global competence is therefore best developed within disciplinary courses or contexts. Students do not develop global competence after they gain fundamental disciplinary knowledge and skills, but rather while they are gaining such knowledge and skills.

Teaching for global competence occurs in the selection of curriculum content and instructional planning that enables students to meet national or local learning expectations such as the Common Core or state standards, while at the same time providing students the chance to frame, analyze, communicate and respond to issues of global significance.

The attached chapter in the forthcoming book, Educating for Global Competence: Preparing Our Youth to Engage the World, offers several case studies. How do students come to understand the problems as they study in their full complexity in age appropriate ways? Students’ understanding of the world is not memorized or merely factual. Rather it is nuanced, flexible, personal and rich.

Most importantly, by exercising independent and critical thinking about matters of global significance, by building on strong content knowledge, by collaborating and deliberating in groups, by evaluating positions and evidence, students are preparing to participate effectively in increasingly demanding educational settings—including college—as well as in their future worlds of work, civic, and community life.