China's Currency Debate

NEW YORK, April 26, 2010 - A large audience at Asia Society headquarters disagreed with the motion: This house believes that China's currency policy is damaging the global economy.

The Peterson Institute's Nicholas R. Lardy argued in favor of this proposition by first detailing how the Chinese government has intervened both in the foreign exchange market to depress the value of its currency and in the domestic money market to halt inflation. The large flow of RMB from China into the US, he argued, created a "search for yields" which contributed to the evolution of the risky financial assets that played a role in the financial problems of the past two years.

Lardy noted specifically that China's global surplus should be more of a concern today than it was in 2006 and 2007. "When a country has a surplus, that means it is selling more into the world than it is buying from the rest of the world, which means that it is reducing global aggregate demand ... in the current environment, China's drag on global growth in the rest of the world is a significantly higher cost."

He conceded that regulatory failures in the US contributed to the crisis, but the market distortions introduced by China's currency policy resulted in its ability to amass a large surplus, hurting both China's domestic market and the global market. "The world would be on a more sustainable path and China itself would be better off if it did not have an economic system that generated such large surpluses."

The Atlantic Council's Albert Keidel spoke against this motion, arguing that the US has abused its seigniorage privilege by flooding other countries with its currency. Although developing countries should run current account surpluses, the willingness of these countries to rely on the stability of the dollar, coupled with the glut of US spending in developing countries, has sucked "out their imports faster than they can actually absorb what would be imports to match it."

Keidel maintained that focusing on China's exchange rate policies ignores other significant structural factors. What was more important than the price effect from China's currency policy was the "deregulation of our financial system that allows leveraging of up to 50 to 1, output of money denominated in dollars that has flowed not only into our housing markets, but into our international transactions as well." Currency is a minor player in damaging the global economy, if a player at all, he concluded.

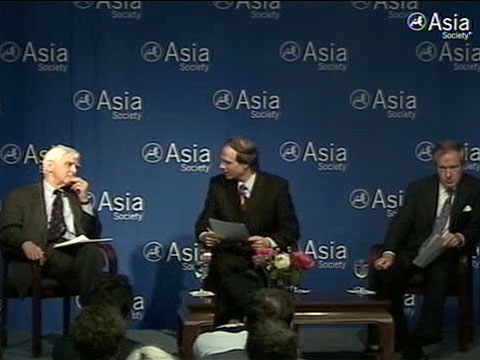

Following the debate, Keidel and Lardy participated in a discussion moderated by the Economist's Leo Abruzzese to elucidate concepts brought up by the speakers and to tackle other topics. The discussion ranged from issues of the effects of currency revaluation on emerging markets to the domestic political stakes for American politicians in branding China as a currency manipulator, especially in light of the upcoming midterm elections.

After hearing statements from both speakers, the audience voted once more on the original resolution. This time, even fewer people agreed with the motion.

Reported by Timothy Orr

The Peterson Institute's Nicholas R. Lardy argued in favor of this proposition by first detailing how the Chinese government has intervened both in the foreign exchange market to depress the value of its currency and in the domestic money market to halt inflation. The large flow of RMB from China into the US, he argued, created a "search for yields" which contributed to the evolution of the risky financial assets that played a role in the financial problems of the past two years.

Lardy noted specifically that China's global surplus should be more of a concern today than it was in 2006 and 2007. "When a country has a surplus, that means it is selling more into the world than it is buying from the rest of the world, which means that it is reducing global aggregate demand ... in the current environment, China's drag on global growth in the rest of the world is a significantly higher cost."

He conceded that regulatory failures in the US contributed to the crisis, but the market distortions introduced by China's currency policy resulted in its ability to amass a large surplus, hurting both China's domestic market and the global market. "The world would be on a more sustainable path and China itself would be better off if it did not have an economic system that generated such large surpluses."

The Atlantic Council's Albert Keidel spoke against this motion, arguing that the US has abused its seigniorage privilege by flooding other countries with its currency. Although developing countries should run current account surpluses, the willingness of these countries to rely on the stability of the dollar, coupled with the glut of US spending in developing countries, has sucked "out their imports faster than they can actually absorb what would be imports to match it."

Keidel maintained that focusing on China's exchange rate policies ignores other significant structural factors. What was more important than the price effect from China's currency policy was the "deregulation of our financial system that allows leveraging of up to 50 to 1, output of money denominated in dollars that has flowed not only into our housing markets, but into our international transactions as well." Currency is a minor player in damaging the global economy, if a player at all, he concluded.

Following the debate, Keidel and Lardy participated in a discussion moderated by the Economist's Leo Abruzzese to elucidate concepts brought up by the speakers and to tackle other topics. The discussion ranged from issues of the effects of currency revaluation on emerging markets to the domestic political stakes for American politicians in branding China as a currency manipulator, especially in light of the upcoming midterm elections.

After hearing statements from both speakers, the audience voted once more on the original resolution. This time, even fewer people agreed with the motion.

Reported by Timothy Orr