Weeding Out Errors Helps Language Bloom

Cultivating high achievement depends on the patient efforts of teachers who are willing to get down in the weeds, so to speak. This is especially true when teaching Chinese as a foreign language, since students’ speech and writing are often marred by misplaced conventions and peculiar errors.

These mistakes are understandable. American students are exposed to English through movies, games, music, as well as interactions in public and at home. Chinese input, meanwhile, is commonly limited to the teacher’s speech and classroom materials. Without correction, students invent alien patterns. As they hear one another repeat them, they begin to think they are normal features of the language, and soon the errors take root like an invasive species of plant. Four teachers, Jing Zhao, Ping Peng, and Qingling Yang from Scenic Heights Elementary, along with Zou Ting at Excelsior Elementary, observed this phenomenon and sought to correct errors while nurturing accepted conventions.

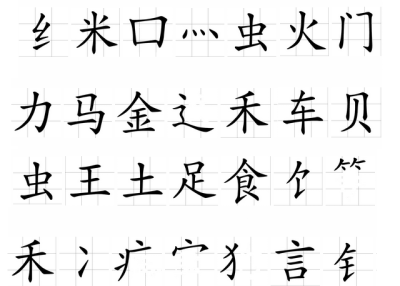

The mistakes that these Minnetonka, Minnesota educators hoped to remedy are pervasive among native English speakers learning Chinese. Grasping for an equivalent of the auxiliary verb “to be,” students unnecessarily insert 是 (shì) before verbs and adjectives. They neglect nuanced measure words (which distinguish the many homonyms in spoken Chinese) in favor of the generic measure word 个 (gè). And, they frequently shift location words, such as 在 (zài) to the end of the sentence, mimicking English but violating Chinese conventions. Puzzled, the four teachers endeavored to understand how these problems become established.

They reviewed the writings of Roy Lyster, Wayne P. Thomas, and Mari Haneda, among others, and discovered that immersion students’ language routinely lacks accuracy and is less complex and socio-linguistically appropriate compared to native speakers. Next, the teachers collected data by videotaping their own classroom interactions. They saw that their students used simple, repetitive language, while they themselves relied on one mode of corrective feedback, called “recasting,” in which the teacher corrects errors by rephrasing. This approach was ineffective, explains Peng, chiefly because students did not recognize the feedback as an indication that they had made a mistake.

Thus, the teachers devised exercises to encourage students to expand their usage and knowledge. In a brainstorm activity, they presented students with a character, such as 天 (tiān/sky), and asked them to think of compounds. Students started with the familiar words 天气 (tiānqì/weather) and soon built up to more specialized vocabulary, such as 天鹅 (tiān’é/swan). Metalinguistic cues, such as reminding students that 天 can be the second part of the compound, prompted students to add 今天 (jīntiān/today) to the list. When students attempted to coin a non-existent word, such as 天猪 (tiānzhū/“sky pig”), the teacher intervened with an explicit correction: “‘Sky-pig’ is not a word.”

The teachers also elevated students’ speaking ability by recasting their mistakes with emphasis and explicit elicitation, which prompted students to self-correct. If students struggled with repairing the mistake, the teachers took the opportunity to give the class a mini-language lesson.

Weekly writing activities, one-on-one conferences, written feedback, encouraging reading aloud multiple times, and peer feedback with rubrics emphasizing both praise and recommendations—all of these strategies embedded good habits in students. Oral reading improved after teachers alerted students to easily confused words like 多 (duō/many) and 都 (dōu/all), enabling them to commend one another for correct language and point out slip-ups.

The teachers also found that when they asked open-ended questions, students were emboldened to experiment with increasingly complex phrases and words, and these in turn yielded opportunities to identify and repair mistakes, ultimately advancing their mastery of both content and language. Zhao explains, “You can see that with a lot more corrective feedback and the teacher’s proper guidance, students get more from prior knowledge and you can reach your content and language goals.”

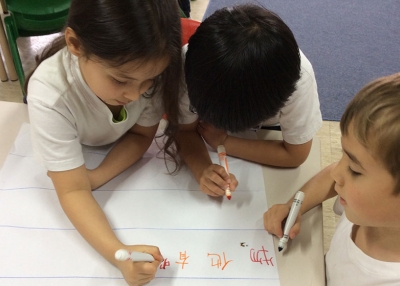

As the four teachers modeled feedback, students followed suit. Posting reminder charts, along with class-established guidelines for feedback, helped everyone spot and remedy recurring mistakes. The data also indicated progress. In early writing samples, 12 out of 19 students placed 在 incorrectly near the end of the sentence, whereas after teachers consistently applied corrective feedback, 16 students placed 在 correctly.

According to Peng, students welcome corrective feedback when the teacher is consistent, positive, and explains its value. She cautions teachers not to be dogged about every blunder, but advises them to focus their efforts on common errors that inhibit communication.

Consistency and perseverance are key. Since corrective feedback can only have lasting results when applied year after year as students progress in their learning, coordinating efforts among teachers in a given school is crucial. If this is done, students’ errors will fade, and beautiful, correct language will thrive.