The Basics of Chinese Immersion Program Design

by Myriam Met and Chris Livaccari

Designing a language immersion program requires a level of commitment on the part of the administration, teachers, students, and parents that is far beyond that of many other types of instructional programs. In making the decision of whether and how to begin an immersion program, it is critical to consider a number of key questions and to clarify the purposes and goals of the program, the student population who will be served, and how the program aligns with other programs within the school or school district. While there are many cognitive and academic advantages to providing students with a rigorous and engaging immersion curriculum, it is crucial to design the appropriate type of program that best meets the needs of students, parents, and the school community.

Definition of Language Immersion

First, it is important to clarify some key terms in the field. For the purposes of this article, a language immersion program is defined as one that involves the use of two languages as the medium of instruction for academic content for no less than 50 percent of the school day. The goal of a language immersion program is to develop a student’s (1) proficiency in English; (2) proficiency in a second language; (3) intercultural competence; and (4) academic performance in the content area, at or above expectations.

For the most part, in this article we will refer to one-way or foreign language immersion, which focuses (in the United States) on populations of students who have little or no exposure to the target language (in this case Mandarin Chinese) when they enter the program. There are also two-way immersion programs, which generally involve equal numbers of English-dominant and Chinese-dominant students, and aim to support both groups in building their skills in both languages. All immersion programs are predicated on the concept of additive bilingualism, the notion that, simply put, two languages are better than one.

There is no better way to learn a language successfully in a school context than in an immersion program. Since the language teacher and the content-area teacher are one and the same, students are exposed to a much richer palette of language and a more sophisticated range of concepts than they would be in traditional foreign language programs. Because teachers must function as both language and content teachers, language immersion programs are cheaper to staff than traditional foreign language programs.

Immersion programs differ by student population, entry grades, parent, and community goals, and most conspicuously by their program model. The program model determines what percentage of instruction is done in English and what percentage in Chinese, and how this changes over time and across grade levels.

Three Critical Questions to Answer

There are three critical questions that someone considering an immersion program should carefully consider.

- What is the fundamental mission of the program?

- What Chinese levels (speaking, listening, reading, writing) do students in immersion programs intend to reach?

- What do immersion programs cost and what needs to be itemized in the budget?

Question 1: What Is the Fundamental Mission of the Program?

In thinking through this question, there are three steps: (1) identify the audience; (2) decide how students will be able to continue expanding their Chinese proficiency after the elementary grades; and (3) define a program model.

Step One: One-Way or Two-Way Immersion?

Pinpointing your audience is an essential starting point. Will the immersion program principally focus on bringing Chinese to a largely monolingual, Anglophone population of students, or are there large numbers of Chinese-speaking students, or students that are speakers of other languages? In addition to the makeup of your student population, take into consideration other segments of your audience: parents, fellow schools, and other members of your community. Does your community include large numbers of native Chinese speakers or heritage learners? Or will students usually come to the program with no prior exposure to the language?

If your program is primarily focused on students with little or no Chinese background, you will be building a one-way immersion program. If, however, your community includes large numbers of Chinese-speaking students, you will likely want to adopt a two-way model that is structured so that both the English-dominant and Chinese-dominant students are able to build their proficiencies in both languages over time. In that case, your program design should include opportunities for the two groups to support each other in their language development.

Step Two: How Long Will the Program Last?

For student language proficiency, both in terms of bilingualism and biliteracy, it is of course ideal to have an immersion program that begins in pre-kindergarten and extends through university. For many schools, however, that is simply not an option. Also, it is important to remember that any program that builds across grade levels—no matter how successful—will see some degree of attrition. To offset this attrition in later grades, any program needs to have a large enough number of students in the program in the early grades. For good retention rates, both students and parents need to be satisfied with the quality of the program. They should see clear and definite gains in language proficiency each and every year; students must continue to be engaged in the program.

For schools that do not have the option of building a pipeline beyond the elementary grades, consider whether and how the students might be able to continue to build their Chinese proficiency in middle school and high school. The problem of articulation across grade levels is critical—too many graduates of successful immersion programs move into programs in later grades that do not allow them to continue to develop their language skills.

Step Three: Which Program Model?

At this point, you should consider identifying the appropriate program model. Originally most US immersion programs were modeled after the Canadian immersion initiative in which students were immersed in their new language 100 percent of the school day. English was introduced at grade 2 or 3 and gradually increased to 50 percent of the elementary school day. Later, US programs began to vary how time was allocated to each language. Today, particularly in Chinese immersion, there are a variety of program models. The majority of Chinese immersion programs divide the K–5 school day according to a fifty-fifty model: 50 percent of instruction is delivered in Chinese and 50 percent in English. Other programs start with 80–100 percent of instruction in Chinese and then offer fifty-fifty in third or fourth grade, for example. (See the Program Profiles throughout the full handbook for examples of program models.)

Program planners recognize that each model has its own set of advantages. It is important to note that all programs eventually are fifty-fifty before the end of elementary school.

For further guidance, you may wish to consult some of the following resources:

- Center for Advanced Research on Language Acquisition (CARLA) website: carla.umn.edu/immersion/index.html

- Center for Applied Linguistics, “Dual Language Program Planner: A Guide for Designing and Implementing Dual Language Programs”

- Center for Applied Linguistics, “The Two-Way Immersion 101: Designing and Implementing a Two-Way Immersion Program at the Elementary Level”

Question 2: What Chinese Levels (Speaking, Listening, Reading, Writing) Do Students in Immersion Programs Reach?

Program Model Goals: Content and Language

Regardless of the program model chosen, all students are expected to demonstrate high proficiency in Chinese, at or above level expectations in English language and literacy as well as subject-matter achievement. However, the grade levels at which students demonstrate these achievements will depend on the program model chosen. For example, students who are in full-day Chinese immersion will probably lag behind their peers on reading and language arts assessments until English is introduced into their school day. These students are also more likely to demonstrate higher levels of Chinese proficiency than students in fifty-fifty programs. Eventually, regardless of program model, all Chinese immersion students should be at or above grade level in all content areas, including English reading and language arts.

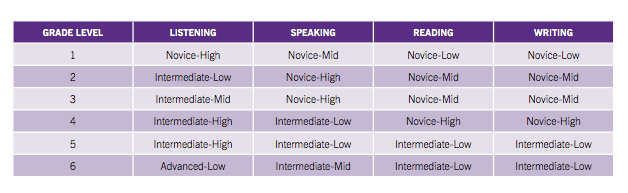

In the matrix below, developed for the fifty-fifty Chinese language immersion programs in Utah, expected performance for students in fifty-fifty programs of Chinese immersion is shown for listening, speaking, reading, and writing. Since Chinese immersion programs are relatively new, there is not yet a significant body of data to determine whether these expectations are appropriate.

It is helpful to set performance expectations in Chinese at the outset of program planning. Knowing what the end result of the program should be—at grade twelve, for instance—allows targets to be set for intermediate milestones, such as at the end of grade eight, then grade five, and grade three. Each milestone then represents appropriate progress toward the next, and is more likely to result in students who meet the intended end-goals of the program. This type of planning, known as backward design, is commonplace in many areas of education—not just immersion

It is important that teachers and program administrators identify ways of determining whether students are achieving program milestones. Some of the measures used will be administered annually, and others less frequently. Some measures will be locally developed tests, teacher observation matrices or rubrics, and student self-reports, such as LinguaFolio. In addition, it is very useful to use periodically, externally developed summative assessments that provide additional information to students, parents, teachers, and administrators about the effectiveness of the program in achieving its goals.

Immersion students are expected to attain high levels of proficiency— levels that are higher than can be achieved in more traditional forms of language education, particularly those that begin in the later grades. Providing opportunities for students to demonstrate their Chinese proficiency, such as high school credit by examination, can be a powerful incentive for students to work to achieve the best possible skills in Chinese as well as to continue participating in immersion or continuation courses.

Question 3: What Do Immersion Programs Cost and What Needs to Be in the Budget?

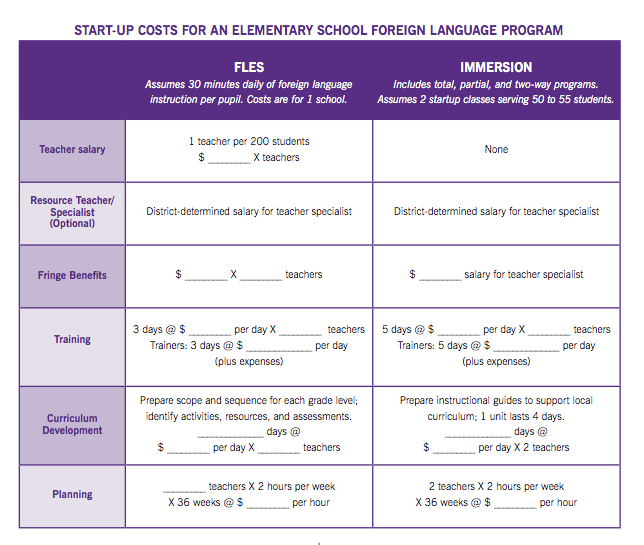

The chart above is useful for planning your program budget. It is important to note that in immersion programs, every faculty member teaches both language and content, and thus there is no additional cost for language teachers, as there is in FLES programs.

Comparisons Between Chinese and Other Language Immersion Programs

Chinese language immersion programs are conceptually similar to other language immersion programs (Spanish, French, etc.) and there are many commonalities for setting proficiency targets, formative assessments, and curriculum design. There are, however, some practical differences between Chinese and other language immersion programs that relate both to the special characteristics of the Chinese language and to the relatively short history of Chinese immersion. These differences include: a relative lack of engaging, high-quality materials; assessments; and language acquisition research specific to young learners of Chinese.

It is also somewhat harder to find a qualified Chinese language teacher and to help new teachers from China adapt to the cultural differences between Chinese and American schools and classrooms. (For more on this topic, see also Asia Society’s report “Meeting the Challenge: Preparing Chinese Language Teachers for American Schools.")

There are some notable challenges related to the nature of the Chinese language; the most significant one involves the development of literacy in Chinese. Chinese writing is unique among world languages in its use of a character-based system that involves both phonetic and meaning elements—almost without exception, all other writing systems in use today rely exclusively on the phonetic.

Developing literacy in Chinese simply takes longer than in any other language, and the difficulty of learning to read and write Chinese is not confined to non-native speakers. It is also true of native Chinese speakers. The other challenge here is that written Chinese (particularly that used for newspapers or other formal communications) combines classical forms of the language with more familiar, colloquial expressions. While written languages tend to be more formal than their spoken counterparts, in Chinese the difference is far more extreme than in most European languages.

In addition to Chinese characters, there is also a phonetic alphabet called pinyin that is used to define pronunciations and to help find words in dictionaries. There are different practices for whether and how to introduce pinyin, particularly for early learners who are also developing literacy in English. The bottom line is that for most students, Chinese literacy will proceed at a slower rate than it would in other languages, especially those languages that are relatively close to English such as Spanish, French, and German.

Another unique feature of the Chinese language is its use of tones. Mandarin, for example, employs four different tones. This means that if you say the same syllable with four different intonations or pitches (high and flat, rising, dipping, or falling), each tone will change the meaning of the word. While these tones can cause considerable difficulty for learners who come to Chinese a bit later in life, early learners can more quickly assimilate them.

The final challenge related to the nature of the Chinese language relates to vocabulary and expressions. Compared to languages like French and Spanish (or even Japanese), there are far fewer words that are cognate with English, and so accumulating new vocabulary is more difficult. Also, since Chinese has been written copiously for several thousand years, there is a vast number of expressions, classical and historical allusions, and other idioms and references to absorb in order to be truly literate.

While all of these challenges suggest that Chinese may be incredibly difficult, it should be noted that the sooner students are exposed to the language, the less daunting all of this will seem. As complex as written Chinese is, remember that Chinese grammar is relatively simple and involves none of the intricate constructions of verb tense or noun declension that are standard in European languages. In Chinese, you can use the same single word to express “I go” or “I went,” “he or she goes,” and so on. And you only need to add another word or a particle to form constructions such as “I will have gone,” “would have gone,” “had gone,” “had been going,” and “would have been going.” In a way, English is actually far more challenging to learn than Chinese!