Private-Public Collaboration Key to Better Treatment of Migrant Workers

Chinese migrant workers leave their factory construction site for a lunch break in Beijing on March 16, 2012. (Mark Ralston/AFP/Getty Images)

Asia Society's Migration Initiative aims to bring policy makers and the private sector together to discuss how to prevent migrant exploitation, while facilitating employment opportunities away from home. The first program, addressing the role of business in preventing trafficking, takes place at Asia Society New York this Tuesday, October 2; complete event details are available here.

Earlier this week, the largest supplier of electronics in the world, Foxconn Technology Group, announced the temporary closure of its factory in Taiyun, China after a 2,000-person brawl erupted in one of its dormitories. Security guards at the company — whose clients include U.S. firms Apple, Hewlett-Packard, and Dell — were reported to have beaten some of the workers, thus sparking the violence.

It's not the first time Foxconn has faced such troubles. In March of this year, the Fair Labor Association, an independent industry auditor, filed a report detailing numerous violations of labor standards in Foxconn factories.

Stories of abusive working conditions, followed by unrest, are common around Asia. Factory workers, largely a migrant workforce, often go on strike in order to contest low wages and long hours and the number of disputes is rising.

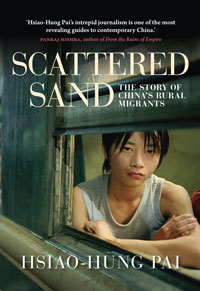

Taiwan-born Hsaio-Hung Pai's new book, Scattered Sand: The Story of China's Rural Migrants (Verso, 2012), tells the story of the conditions faced by the armies of Chinese migrant workers who make the trek away from home to various industrial zones, mines, and even cities of the West. Their stories are seldom positive, but rather present a portrait of abject hardship and frequent suffering: withheld wages, confiscated documents, and significant debt.

While events like those at Foxconn this week are increasingly frequent, incidents such as these are thus far largely contained to the industrial parks where they occur. As a migrant interviewed in Pai's book says: "We are like scattered sand — there are millions of us, but without power as the largest army of workers."

In Asia, and around the world, stories of migration are typically fraught with hardship, grief, and also occasional success. Regardless of the type of political system, whether democratic, authoritarian, or a hybrid of the two, migrants are often left to struggle while societies profit from their hard work.

But contemporary issues facing migrants are a mirror of the past.

Upton Sinclair's 1906 novel The Jungle detailed the situation of migrants in America more than a century ago. The Jungle's protagonist, the Lithuanian immigrant Jurgis, has high expectations of life abroad, but gets swindled by agents on the passage over, duped by his employers, and finally coerced into signing a contract on a house that they could never afford.

Some would argue that little has improved with respect to the situation faced by many migrants in America today. As was the case in the U.S. in 1906, migrants lack the social capital to demand treatment that is equivalent to their non-migrant peers. The result is social unrest that has the potential to flare up into larger-scale violence, as happened in Sinclair's description of Packingtown, on the outskirts of Chicago.

Much of the abuse is owed to the strong link that often exists between business and policy makers, and the fact that local residents have little incentive to demand better conditions for foreigners. In Asia, as in the U.S., business benefits from a cheap, reliable labor force that can be coerced into working long hours without protest. Rules are seldom enforced as they are trumped by the demands of the private sector for inexpensive labor in low and semi-skilled sectors. Even if migration occurs through legal means, migrants often face much more tenuous conditions than their local peers.

There is much discussion about public private partnerships (PPP) these days, particularly in the international development community. The idea is that the private sector is able to enact policy efficiently, and that corporations can work to protect the communities where they work.

It is especially in the area of migration, however, where PPP might not just be the pursuit of a just cause. Rather, it is an opportunity for corporations to effect change, and for them to reap the benefits of increased stability and favorable public perceptions.

Just because migrants often lack the agency to demand better conditions, lack knowledge of destination conditions and cultures, or are different in physical appearance, there is never an excuse to take advantage of their desire to move ahead in life. Migrants can, and do, eventually achieve the equal status they desire, but impeding their progress unnecessarily, by way of bureaucratic measures, only offers opportunity for private agents to profit from their desire to better the lives of themselves and their families.

Scattered Sand warns that "not all migrants are willing to bear the brunt of the economic crisis while multinational companies continue to rake in profits." Having worked on migration issues in various parts of Asia and the Middle East, I have been witness to this discontent. Whether Egyptian workers waiting by the side of the road for construction jobs in Jordan, or Bangladeshi migrants being carted around Singapore on the back of flatbed trucks, the conditions they face are often significantly worse than the local populations, and there is the potential, even if poorly organized, for there to be unrest.

Companies — by virtue of needing labor at all skill levels — should have a greater voice in working with policy makers to shape laws that facilitate legal movements of people between and within countries without impediment. But more importantly, a new migration regime, where business recognizes that a well looked after workforce is a more productive workforce, would also benefit politicians who profit from stable societies.