Interview: Translator Motoyuki Shibata on Manga, Murakami and Monkey Business

Widely referred to as Japan's leading translator of contemporary American literature, Motoyuki Shibata has been responsible for rendering American writers as diverse as Thomas Pynchon, Paul Auster, Richard Powers and Edward Gorey into Japanese. As a sign of his linguistic prowess, Shibata was awarded the Japan Translation Cultural Prize for his 2010 translation of Pynchon's Mason & Dixon, a feat that will undoubtedly impress any reader who encountered that literary leviathan in its original language.

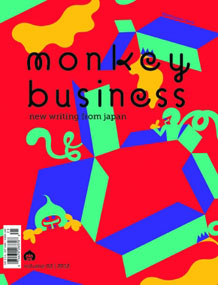

Working the other side of the street, meanwhile, Shibata is bringing the current generation of Japanese writers before an international audience via his English-language literary journal Monkey Business: New Writing from Japan, the second issue of which has just been published.

Shibata appears with a panel of American and Japanese writers at Asia Society New York this Sunday, May 6, as part of a special Japan/America Writers Dialogue tied to the launch of Monkey Business Issue Two. The panel is a co-presentation with The Japan Foundation, in association with the 2012 PEN World Voices Festival. (For those who can't attend in person, the program will also be a free live webcast on AsiaSociety.org/Live from 2:00 to 4:00 pm ET.)

Asia Blog reached out to Shibata via email a few days ahead of his Asia Society appearance.

For years we've been hearing that Americans are less and less interested in foreign literature. Do you find this to be the case — and is Monkey Business an attempt to counter that tendency?

I keep hearing that, but I wonder if it's really so. Writers who have appeared most frequently in the last couple of years in Harper's and The New Yorker are Roberto Bolaño, Haruki Murakami and Alice Munro: only one English-language writer out of three, none of them American. Isn't that pretty good?

Besides, all the great non-English writers I discovered in the last two decades — Bolaño, Milorad Pavić, Danilo Kiš and W. G. Sebald — I discovered them through English translations published by American publishers.

Haruki Murakami, the best-known Japanese writer in the world, appears in both issues of Monkey Business — first as an interview subject, and then as an essayist. Has Murakami's visibility made it harder, or easier, for other Japanese writers to gain international exposure? I'm curious to learn who the other contemporary Japanese writers are that we in the U.S. should know about.

If it were not for Haruki, I doubt that there would be this much interest in contemporary Japanese fiction in general. Without Haruki there would be no English Monkey Business! And yes, of course there are many other terrific writers in Japan today. To find out who they are, read Monkey Business!

Both issues of Monkey Business include manga [Japanese comics] alongside short stories, essays and haiku. Has the manga form always had literary respectability in Japan? (Here in the U.S. it took decades for graphic novels to be taken seriously by the literary establishment.)

Both issues of Monkey Business include manga [Japanese comics] alongside short stories, essays and haiku. Has the manga form always had literary respectability in Japan? (Here in the U.S. it took decades for graphic novels to be taken seriously by the literary establishment.)

Not manga in general, but there has always been literary manga of extremely high quality since the 1960s. Fumiko Takano, who appears in the second issue of Monkey Business, is almost a legendary figure, and the Nishioka brother and sister who appear in both issues are a cult pair with highly passionate followers.

Tim Parks, writing in the New York Review of Books, recently expressed a concern that younger writers around the world are flattening their language, stripping it of complexity and nuance, so as to make it more easily rendered into English (and thereby accessible to a global market).

Are these concerns overstated? Have you witnessed anything like this tendency in your years on the international literary scene?

It's certainly NOT the case with many young Japanese writers. Writers like Hideo Furukawa, Mieko Kawakami (both of whom are our regulars) and Kō Machida really make the Japanese language work — they are so versatile, mixing many different voices, sometimes within a single sentence.

In English-speaking countries, there are writers who appear to be relatively easy to translate into other languages, such as Kazuo Ishiguro, but you can't call Ishiguro's language flat: his style is none the poorer for being seemingly simple. For most authors, for most good ones, style is like fate — you can't choose it. No one worth their salt writes for the market, even if they may think of it.