Interview: Son of Myanmar Midi Z Returns Home to Tell Its Tales On Screen

Asia Society Museum’s history-making exhibition, Buddhist Art of Myanmar, opens February 10, 2015, in New York. Exploring Buddhist narratives and regional styles, Buddhist Art of Myanmar is the first exhibition in the West to focus on art from collections in Myanmar. Learn more

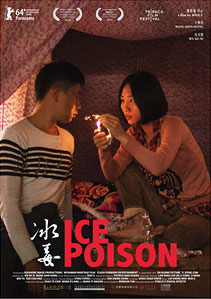

In Ice Poison (2014), the most celebrated film to date by Myanmar-born and Taiwan-based filmmaker Midi Z, which opens Asia Society’s March 6 through 13 retrospective of the director, a young woman, Sanmei (Wu Ke-Xi), returns home to Lashio, Myanmar from China to bury her grandfather. Like many other impoverished women from the region, she was tricked into marrying a Chinese man. Trapped in a loveless union, she hopes to stay in Myanmar and earn enough money in order to bring her son in China to join her. With few ways to make money, Sanmei winds up delivering ice (crystal meth) with the help of scooter taxi driver Xing-Hong (Wang Shin-Hong), who is also desperate for cash.

Although Sanmei is bold and Shin-Hong is reserved, they become natural partners in the delivery business, traveling from one customer to another, snorting ice, and developing a delicate, unspoken romance. With no gangsters in sight, no blood spilled, and no guns drawn, danger lies mostly off screen. What we see are simply two ordinary people finding company and a way to survive in the harsh countryside of Myanmar.

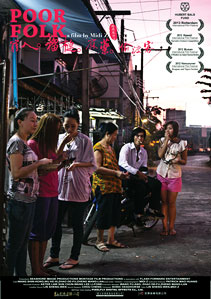

This is typical of how Z portrays life as it is experienced by the people he is familiar with from growing up in an ethnic Chinese community in Lashio. His feature films, which also include Return to Burma (2011) and Poor Folk (2012), take him back to Myanmar a decade after he moved to Taiwan at the age of 16. With a deep personal understanding of these individuals’ circumstances, Z presents life stripped of drama and sentimentality; his realism is honest, nonjudgmental, and filled with compassion.

I spoke with the director in his Taiwan home via the Internet before he traveled to Myanmar to celebrate Lunar New Year with his family and to set up an office in Yangon. We had the opportunity to talk about his background, contemplate what his life would have been like had he stayed in Myanmar, and discuss how he brings the stories of his family and friends to the big screen.

(Note: In 1989, “Myanmar” replaced “Burma” as the official name of the country. Many Myanmar people still call their country “Burma,” as does Midi Z in this interview — and his first feature film is entitled Return to Burma.)

This spring, Asia Society New York presents Myanmar's Moment, a season of programming that will include talks, films, and performances exploring Myanmar’s past, present, and future. Learn more

The characters in your films are based on the people you are familiar with from growing up in Lashio. They’re poor and many are displaced, often moving from one place to another. Trying to find opportunities for a better life, many have to work illegally, in drug and human trafficking, for example. What was your upbringing like? Were you close, personally, to those experiences?

Of course. Some of my relatives, friends, and my eldest brother sneaked into Thailand to work there illegally. It’s quite common for us. When I was 10 years old, I crossed the border to China with my uncle to buy sugar during Chinese New Year, and then returned home to sell it. Crossing the border is common for people like us who reside near the border. At that time, everybody crossed the border illegally. We didn’t have the passport back then. In fact, we didn’t need one. Instead, we needed a temporary ID, a one-week permit, to visit China or Thailand. However, it was very expensive to get it.

What’s your family’s economic background?

My mom ran a very small noodle shop, which was not a very stable business. My father was sick quite often, even though he’s a doctor. Besides running the noodle shop, my mom also worked as a cook for weddings. My eldest brother worked as a jade miner and sent us money, but not very often, only once in three years. Mostly, our mother took care of us.

A lot of characters in your films have no choice but to work in illegal trades. I’m wondering if you thought you could have ended up like them.

Of course. Before I came to Taiwan, I had a plan to work as a drug dealer. I did plan that. I have to say that if I didn’t come to Taiwan, I could have been a gangster, a drug dealer, or a minority in the army. I did plan to work with my friends and relatives [to sell drugs] when I was 14 after graduating from junior high school.

'Ice Poison' (2014)

Does that explain why you portray the characters in your films in such a nonjudgmental manner?

Yes. Once you know their realities deeply, you can have a more objective view to tell their stories. Like the drug dealers in my films, they are just making a living. When they help carry drugs or amphetamine, they might just get 10 kilos of rice in pay. My relatives are not the kind of drug dealers or mafia gangsters you see in Hollywood films. In my stories, even though the characters deal drugs and traffic in humans, they are just ordinary people.

Your life changed completely after you went to Taiwan. How did you end up there?

Sometimes, when I think about my past, I find my previous life very unreal. When I passed the exam held by the Taiwanese government to study there [on a scholarship], my mom and sister supported me by getting me a passport, which wasn’t easy at all at that time. We needed half a million kyat, which was enough to buy a house. It was very difficult. My sister was working in Thailand. She sent me some money and my mom borrowed the rest to get me the passport to escape my hometown. Before I passed the exam, I felt bored and wanted change every day. Everyone hoped to go somewhere, anywhere but my hometown. I was very excited when I knew I could go to Taiwan. I didn’t go to Taiwan to study. My goal was to work and send a lot of money home. That’s the situation.

During high school in Taiwan, I spent most of the time working in a restaurant. On holidays, I worked as a construction worker. I was very lucky. My friend back home gave me money to buy a video camera for his wedding. In the end, the video camera couldn’t be sent to Burma. So I began using it to make wedding videos. It was the beginning of filmmaking for me, and it changed everything.

It took you a decade to go back to Myanmar for the first time. Why did it take so long?

It was stated in our passports that we couldn’t go to North Korea or Taiwan. A [former] President [Chun Doo-Hwan] of South Korea was assassinated by North Korean agents in Burma [in 1983]. As for Taiwan, I think the government of [the People’s Republic of] China forced the Burmese government to make this policy. I didn’t get a visa for Taiwan in my passport. I got a visa for Thailand instead. I went to Bangkok first as a one-week tourist before traveling to Taiwan. My passport was valid for only one year. So I couldn’t go back to Burma. 10 years later, the policies changed. It’s the first reason why it took so long for me to return home. The second reason is that it’s very expensive and complicated to travel from Taiwan to Burma. There’re no direct flights. We had to travel through Thailand or Hong Kong, but I couldn’t get a visa for either.

Even after 10 years, in 2008, I needed to use an agent to bribe an immigration officer so that my name could be on the officer’s notebook. When I arrived at the airport, the officer came to me to take away my passport, which I had to surrender. It was scary. It wasn’t like I felt excited to go back home after 10 years.

How was it like to return to Myanmar after 10 years?

It’s difficult to describe. When I went back to Burma, I felt that everything had remained the same. There were more roads but nothing really had changed. When I saw my mom after all those years, the first thing she said was, “Have you eaten your lunch?”

How did you decide to make your first feature film in Myanmar?

By accident. I didn’t make any decision. At that time, in 2010, I was planning to become a commercial director in Taiwan or to run a production studio in Burma, maybe to make wedding videos. Everybody told me that Burma was going to change with its first democratic election [in two decades]. I went back to see what I could do. That’s all. I was not sure. I had written a script, which wasn’t the script for Return to Burma. It was a very dramatic script. I asked for funds from some production studios in Taiwan and contracted an actor. Three weeks before we went to Burma, the actor disappeared. So we didn’t get the actor, nor the budget. I then decided to shoot a documentary about whatever was happening in Burma, which ended up becoming [the fiction film] Return to Burma.

Can you describe the crew you had?

We had a very small crew. I had my production manager and a sound engineer. Three of us, with a small digital camera, we flew to Burma.

Your production manager [Wang Shin-Hong] also became the lead actor. How did that happen?

He was my neighbor’s relative. We were eighth-grade classmates in Burma. He came to Taiwan three years after me. When I made my graduation short at the National Taiwan University of Science and Technology, he was studying at the National Taiwan University. I asked him to work as my production manager. He also played a role in my short film. He became the lead actor of Return to Burma because we didn’t have a choice. We had asked the locals but they didn’t want to participate. They didn’t understand what we were doing. Also, holding a camera on the streets of Burma could be a very dangerous thing. The atmosphere was very sensitive.

Your films look very authentic, especially their casts. Most of them are nonprofessionals. Can you talk about that?

I don’t think they need any training in order to act. They have many life experiences. Their presence is already very powerful in itself. Their faces tell a lot of stories. Before I begin to shoot, I spend a lot of time talking to them or listening to their life stories. Many are very lonely and they need someone to listen to their stories. That’s how my auditions are. For example, the father in Ice Poison does have a son who uses amphetamine. He is a real farmer whose cow was also slaughtered. All of the characters are real. They just express their real feelings. Even though the settings are fake, the emotions are real. Almost all the characters in my films are nonprofessionals, with the exception of [the female lead] Wu Ke-Xi.

'Poor Folk' (2012)

Your films were shot on location. Did you get permissions?

I didn’t get any permission to shoot. In Burma, it’s hard to get a permit. We also didn’t have much time to plan the shoot for Poor Folk. I had a rough plot structure, and we just started to do it. I realized that we could really shoot without a big crew or budget. For Return to Burma and Ice Poison, we did try to get permissions but our scripts didn’t get the approval since they were too realistic. We ended up shooting underground. We pretended to be tourists, like we were just taking pictures of the scenery.

Was it dangerous for you to do that?

Actually, it’s very dangerous. Someone once told the police that we were filming at a public bus station. The police came, and we explained that we were making a short film to teach local students how to make films.

Does that explain why your films aren’t shown in Myanmar?

Yes. I also didn’t apply for the public screening permits. I didn’t think I could get them. A friend of mine shot a film without permission. When he applied for a public screening permit, he wasn’t granted one.

Myanmar has changed a lot in recent years. It’s opening up politically and economically. Have you observed real changes in people’s lives?

For me, the changes are too slow. I think the changes occur only in appearance. Nothing has really changed, for example health care. Even though the economy is changing, it doesn’t necessarily mean that the poor can also get a chance to change their lives.

You’re planning to set up an office in Yangon. What’s the intent behind that?

I want to work with local young people. Unlike me, local artists have no access to information and resources. I want to bring these back to Burma, and that’s the main reason why I want to set up an office there.

Midi Z and actress Wu Ke-Xi will appear in Q&A sessions following screenings at Asia Society New York on March 6 and 7.